As we were walking through the fifth floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2017 Biennial, I yanked my companion into a side room full of chairs and tables so that we could be alone. Wrapped up in conversation—my friend needed to talk something through—I absent-mindedly toyed with some paper on the table in front of me, assuming it was a press release. I glanced down at the paper in my hand, then around. My stomach dropped. My gaze fixed on a piece of wall text on the other side of the room. Were we sitting on…art?

We were. I think it must have been an installation by Chemi Rosado-Seijo. (We ran before we could check.) The Whitney’s website describes the piece this way: “A gallery from the [Biennial] exhibition has been ‘moved’ to the Lower Manhattan Arts Academy,” a public high school, while “a classroom from the school has been moved to the Whitney.” The swapped spaces constitute Rosado-Seijo’s work, which is titled Salón-Sala-Salón. The kids come to the museum for their lessons, while art by Sky Hopinka and Jessi Reaves sits at their school.

If they ever find out what we did, I hope that Rosado-Seijo and the Biennial’s curators will not be angry. Our need at the time was sincere, and so is Rosado-Seijo’s work. At its deepest level, this enormous show of contemporary American art is about just that—sincerity.

In his opening remarks, the Whitney’s director Adam Weinberg stood silhouetted against the window to the Hudson, frustrating all the photographers. From atop his podium Weinberg told the assembled journalists that shows of this kind should be a “platform for collective action.” In such times, artists need to mean what they say. “Irony, be gone,” he bellowed, though he laughed right afterward.

Weinberg described the Biennial artists as both “receptors and transmitters.” When this year’s curators Mia Locks and Christopher Y. Lew (both gorgeous and in their mid-30s) clambered onto the podium to give their remarks, they also praised their “receptive” chosen ones. They didn’t mean “receptive” in the sense of willing to take feedback. They were suggesting that this year’s artists receive and transmit signals from and to the world around them. Like two-way radios.

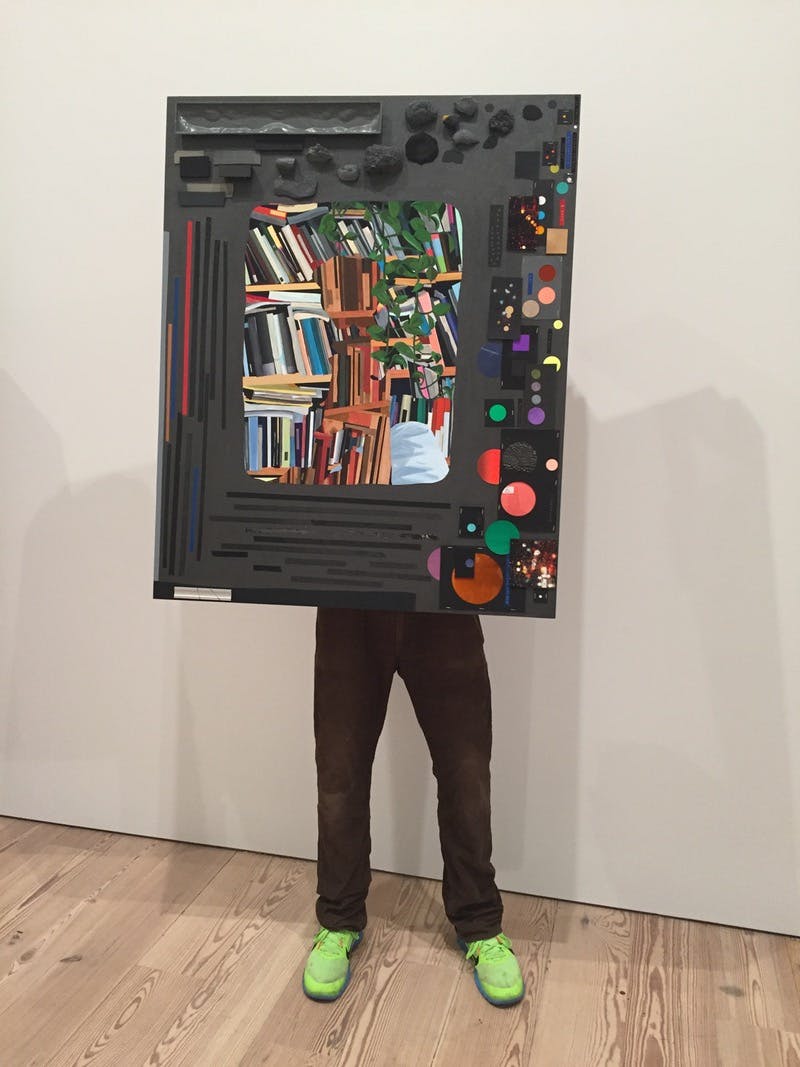

John Riepenhoff’s work functions in this way. Riepenhoff is an artist and gallerist from Milwaukee, a city where “nobody is really buying art,” in his words. Every time he said the word “Milwaukee” he smiled slightly from behind his clear plastic–framed glasses. My friend recognized Riepenhoff from his legs: His art consists of reproductions of his own lower half, dressed in his own trousers and underwear and sneakers, holding up other people’s work, like stands. This work comes out of the idea of “being an artist’s assistant, being a support structure for art.”

The stands riff on the art assistant or handler’s job of moving around artworks until they’re the right height, the physical labor of actually holding the pieces before they are displayed. One of the displayed pieces held up by Riepenhoff’s legs was from the Whitney’s own collection, a joint work by the Society of Independent Artists, the important 1910s avant garde collective. I told Riepenhoff that I thought his art was very sweet, and he laughed. “I feel like this is the kids’ floor,” he said. “There’s a soft playfulness to it. There’s sincerity here, but that doesn’t mean you can’t be funny.”

Carrie Moyer, who like Riepenhoff was exhibited on the fifth floor, makes big, rhythmic paintings. They contain large shapes that do not seem quite made by human hand. The shapes seem born of themselves, or from some other dimension. This work is intended as an “antidote to anxiety,” Moyer told me. Music and dance and feeling form these shapes, not comment. “This is not ironic,” she said.

Not all on this floor is sunny. Right after the sitting-on-art incident, my friend and I ran into a darkened film room, where we figured nobody could find us. There, we watched Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s film The Island, a fantasy piece shot on the Malaysian island, Pulau Bidong. The island officially became a refugee camp for those displaced by the Vietnam War in 1978. By 1979, it was one of the most densely crowded places on earth. The United Nations shut it down in 1991, and now the former camp is overgrown and jungly.

Nguyen’s film follows a man who believes he is the earth’s last survivor, until he finds a scientist washed up on his island’s shore. It is a sad story that is also tinted by the magical. This work is about death and American destruction, but also green leaves and memory and family. Home, in other words.

These themes—sincerity, sweetness, remembrance, trauma, home—do not contradict one another, although they tip from light to dark and back again. On the sixth floor, I saw what Riepenhoff was talking about. This is a more serious space, focused on America’s present. One of the first things you see is Puppies Puppies’ Triggers. Three gun triggers have been stripped from their intended instrument and fixed at around neck level on the wall. Without wanting to reduce these objects to their figurative meaning, the piece reminds us that trigger warnings come from the idea that a pulled lever (a word, a piece of metal and plastic) can wound.

Around the corner sits the show’s most coherent room. Deana Lawson’s photographs show intimate but highly staged moments in the interiors of black homes. In Ring Bearer, a young boy in formal dress holds the ring on a heart-shaped cushion, beside a proud-looking older lady, presumably his grandmother or some other relation. These domestic scenes are a little sad in places—nobody is smiling—but they have a strong core. They are photographs with a sense of self and a backbone and a direct gaze.

Between them, Henry Taylor’s large and decorative paintings hang. His shapes are so big and bright that they would overwhelm Lawson’s work if there weren’t enough space between them. These are scenes from black life amplified to the bright bold level of myth or legend. Philando Castile lies back under a twisting and gorgeous seatbelt. A big horse rides behind a worried face, with nothing else in the distance.

This room is successful because Taylor and Lawson’s works take our moment and pull them out of time. Consider this moment as if it were not historical, their works say. Think about how black life and death looks, think about the different approaches we two are taking. What is left out, and what do you bring here, viewer? Who are you, to this room?

Mia Locks and Christopher Y. Lew have both written essays to accompany their Biennial. Locks’s is called “Being With Other People.” “These are turbulent times,” she writes. “And the turbulence affects you, infects you, seeps in.” She makes it sound like our national disaster is a disease or a liquid, or both. Lew’s “All Together Now (You Better Work)” plays with the same concept. He quotes RuPaul describing the television show Drag Race: “Yes, we’re a competition reality show, but because we’re doing it in drag, other levels of consciousness seep in.”

We have the seeping infection of our hard-right administration, but we also have a seeping consciousness that has something to do with art. Lew calls that something “an awareness of the continued necessity to investigate and invest in the self, the true ‘you’ that refuses to be defined by the powers that be.” This greater consciousness, he says, is “crucial to the 2017 Whitney Biennial.”

“Reflection,” Mia Locks writes, “is only one strategy by which art is social and political, and even so, art doesn’t merely reflect social life; it contributes to it, through a range of means and methodologies, materials and forms.” My friend and I disrespected an artwork when we pulled out its chairs and sat down, but perhaps we were also engaging with the work in a mode that veered away from reflection. We engaged through use, finding an aspect in the artwork that met our need as human beings in this country.

Lew writes that “the Whitney Biennial sees the ideals at the center of the American experiment not as a broken dream forever irreparable but as fertile ground that must still be worked.” An experiment is a process full of breaks and failures. Tears even, and anger, and friends in side rooms having urgent conversations. This is not a conclusive exhibition, but experiments are not conclusions. America, that restless concept, is the Whitney Biennial’s only real rubric, and Locks and Lew have managed to assemble a full choir of voices without ever making the work of “representation” feel laborious. Sincerity, sweetness, remembrance, and trauma—these are stages in an ever-working cycle manufacturing the idea of home.

As Locks notes in the final sentence of her catalogue essay, shows like these put us “face to face with ourselves.” There is so much to see.