Women are the shock absorbers of neoliberalism. When wages stagnate, as they did for nearly a decade following the financial crisis, women are expected to work more. When the state decides to shred the social safety net, as the GOP threatens to do, women are burdened with an obligation to care for others, particularly children. From both sides and under the gaze of a misogynist president, the American woman is being squeezed. As Sarah Leonard of The Nation told me, “Something’s got to give.”

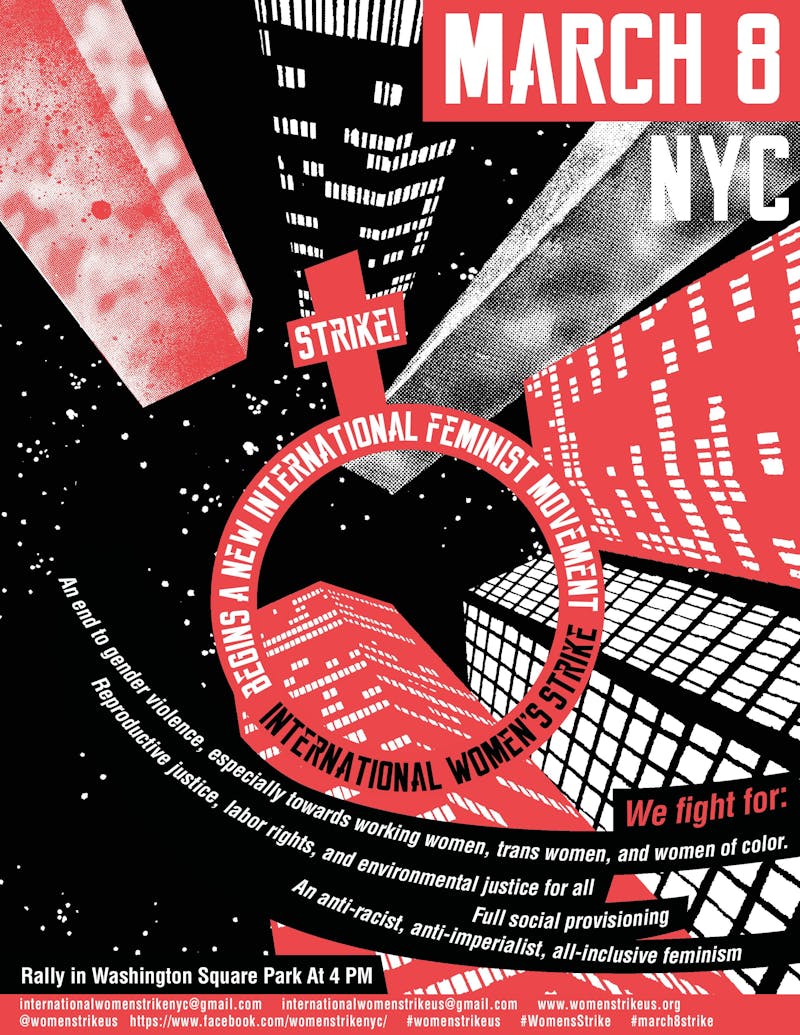

Tomorrow, women across the world will down tools in the International Women’s Strike, a day of action calling attention to the value of women’s labor. Leonard is one of the organizers behind the action in the U.S., which is just one of more than 50 countries participating. When we spoke, she explained that she was driven by a wish to reaffirm “a feminism of the 99 percent.” As Bryce Covert wrote in The New Republic earlier today, the planned action will take place on International Women’s Day, which initially commemorated “a strike staged by tens of thousands of female garment workers in New York City in 1908.”

Beyond this history of industrial labor, women of all kinds (cis, trans, straight, queer) do all kinds of work, recognized and unrecognized. They labor in workplaces, where they are paid wages (although usually less than men). But women also work in other arenas, “raising children, cleaning, housework, all of the things that women have traditionally done to keep society functioning,” Leonard said. All women are united by the fact that our labor is undervalued. A feminism of the 99 percent, and the strike which celebrates it, brings together women workers in solidarity with one another.

The idea of a strike is to make that labor visible by forcing people to do without it. “There are many ways to go on strike,” Leonard said. A woman can “not go to work,” or “refuse to do housework,” or “boycott a business that engages in misogynistic practices.” You can “refuse to smile, you can refuse to do emotional labor, you can refuse to fuck.” Absence makes the labor visible. If you can’t strike, the IWS organizers ask that you wear red, or a red ribbon, to mark visible solidarity with others undertaking actions.

Kate Doyle Griffiths, another organizer behind the American IWS, echoed Leonard’s focus on solidarity and communication, saying the strike is an opportunity to build relationships. If you can’t walk out but you can wear red, she said, “you might invite more discussion and communication with your coworkers.” Griffiths has heard of people who are “holding mini-rallies and meetings at lunch.” The connections women already have at work are the channels through which they can support the strike, but also the means to “talk about the problems they share in the workplace that need solutions.”

By the same token, Griffiths sees this as a moment for women to discuss unpaid labor: “This is a good time to build community and networks that can share in the task of raising kids, cooking, cleaning.” Just because you don’t walk out of work does not mean you are not a part of this day of action: You can help another woman with her care duties. “The important thing to remember,” Griffiths said, “is that collective action is a muscle that only gets stronger when you exercise it.”

Suzanne Adely is a longtime Arab community organizer and lawyer based in New York and a member of the IWS national planning committee. She joined the committee, she told me, in part out of “deep respect” for the women who first called for the U.S. strike: Tithi Bhattacharya, Keeanga Taylor, Rasmea Odeh, Angela Davis. Adely is particularly keen to build a feminist platform that “includes a critical socialist, anti-neoliberal, and anti-colonial analysis.”

Adely is global in her historical thinking. She cited as inspiration the women-led textile strike of 1912 in Lawrence, Massachusetts, which included laborers of over 40 nationalities, and the 2015 women tea workers strike in Kerala, India, which took place “in defiance of their male union leadership, winning demands for higher wages, better working conditions, and labor rights.” Meanwhile, at home, “migrant women workers in organizations like Desis Rising Up and Moving” continue important worker battles every day. These examples, Adely said, “remind us that fighting class struggle, fighting racism, and fighting imperialism must come together.”

Kate Doyle Griffiths also looked to home for inspiration. In particular, she cited the 1969 events at Stonewall and the gay liberation movement that followed, “led by trans women of color like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha Johnson, by drag queens, sex workers and their clients.” The Italian 1970s feminist campaign for Wages for Housework animates Sarah Leonard. Women at the time were involved in organizing labor, but “were not being respected and valued.” Although they were doing things like housework and bearing children and caring for workers, women’s labor was not waged and was therefore not included in the traditional Marxist concept of value. The movement demanded wages for housework “as a way of recognizing that what they did was work.” Men within the Italian Left at the time showed up to their meetings and threw rocks.

I asked Sarah Leonard: What would you tell a woman who was nervous about leaving her workplace on Wednesday? First, she referred to a variety of letters up at the organizer’s website, which women can use to explain the strike to bosses or partners or colleagues. These resources aim to “develop a language for talking about gender,” Leonard said, to help people to begin to have these conversations.

And conversation is the ideal starting point. If a woman has an interest in or feels inspired by the women’s strike, Leonard pointed out, it’s probably because she thinks that “something is not fair.” Maybe her workplace has issues with childcare or unfair wages, or the women in her workplace have noticed that they seem to be doing all the work at home and the office. These are things that women should be expressing to their colleagues. They are everyday concerns, nothing exotic.

A woman taking action does not have to go out to a protest, but Leonard encourages people to “come out and see.” As with the huge Women’s March in January, she said that participants will see that the base for the strike is really very broad. These are issues affecting “society at large,” not a niche interest group. The majority of us think that President Donald Trump has gone too far: The March showed us that many thousands of ordinary people will turn out for the sake of maintaining a functioning civil society. For this is a fairly basic cause: “It’s very rare that you’ll meet someone who will say, ‘I don’t think everyone should have access to child care, I don’t think everyone should be able to go to the doctor,’” Leonard said. Again, these are not exotic issues.

Writing at n+1’s website, editor Dayna Tortorici exhorted women to join the action. She explained that “the Women’s Strike is not only about women,” but about women’s work. As traditional labor configurations have eroded in recent decades, Tortorici (quoting Maria Mies) wrote that more of us are working under conditions hitherto “typical for women only.” Such work is done without unions or contracts, or through agencies. Permalancers work more like women under these conditions. “This is what is meant by the phrase ‘the feminization of labor,’” Tortorici argued. This means not that men are emasculated but that “men are treated like shit as workers—that is, like women.”

In an essay for The Nation, Griffiths and Magally A. Miranda Alcazar placed the IWS in the context of other recent actions going on across America and the world. “It’s well known that queer black women played the central role in building Black Lives Matter as a national force,” they wrote. They also referred to the February 16 action “Day Without An Immigrant,” which was preceded by a huge local walkout in Milwaukee for “Day Without a Latinx, Immigrant or Refugee.”

The Nation article took on the burden of replying to Sady Doyle’s assertion in Elle that striking is a “privilege” only afforded women who can walk out without fear of repercussion. By pointing to the rich and recent history of women-led actions in America, Miranda Alcazar and Griffiths were able to reverse her formulation: “Striking is not a privilege. Privilege is not having to strike.”

Wealthy white women like Hillary Clinton or Cheryl Sandberg are held up as beacons of feminist discourse. But they are not of the 99 percent. They’re the faces of feminism, while real women are suffering under the radical inequality that flourishes in our economic system. “Reclaiming that feminist mantle is a big, big part of the strike that we’re organizing,” Leonard told me. The most vulnerable women in the country have been making a difference through “risky organizing” this year and last year and in years before that. We honor their work when we strike in solidarity with them tomorrow.