In the 2016 election, it was common for centrist conservatives and liberals to treat the populist fervor animating the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump as two sides of the same coin. Jonathan Capehart at The Washington Post went as far as to claim that Sanders and Trump share the “same DNA.” Post-election, conservative organizations like Fox News picked up the thread, using the term “alt-left” to frame the Democratic wing led by Sanders and Elizabeth Warren as extreme. At the dawn of the Trump era, this trend has shown no signs of flagging. In the past week, we have seen prominent liberals once again demonizing the left and even appropriating the language of the talk radio right—a tactic that is as misguided as it is unhelpful.

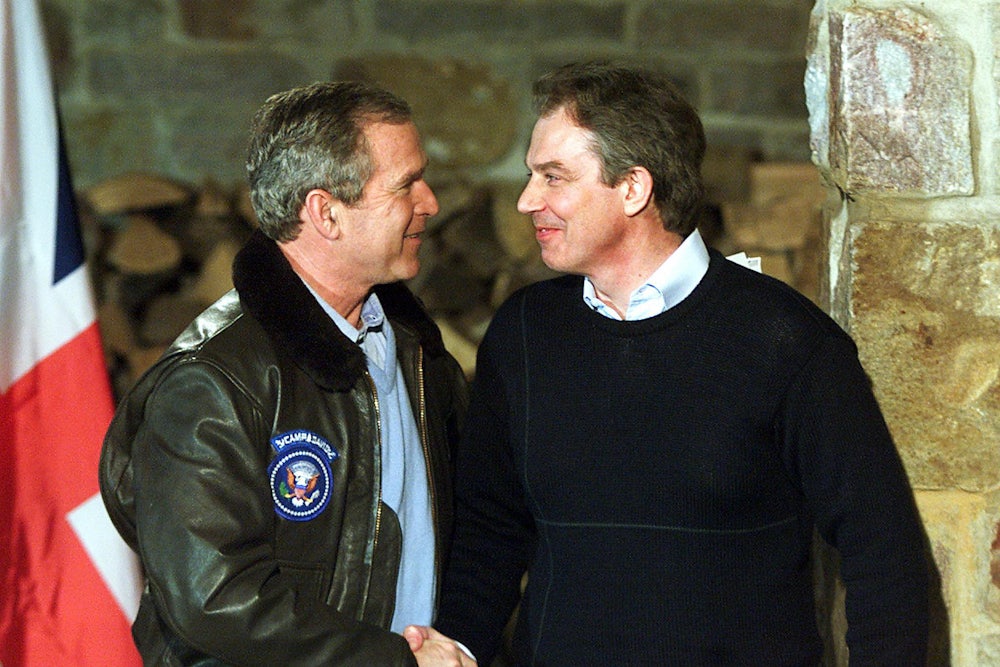

In a piece published on Vanity Fair’s website on Friday, the critic James Wolcott argued that the “alt-left” is a “mirror image distortion” of the alt-right. Wolcott wrote that the two movements are “not kissin’ cousins, but they caterwaul some of the same tunes in different keys.” He argued that the alt-left’s “dude-bros and ‘purity progressives’ exert a powerful reality-distortion field online and foster factionalism on the lib-left.” In a less bombastic yet more insidious op-ed column in The New York Times, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair claimed that the populist left has adopted many traits of the populist right:

One element has aligned with the right in revolt against globalization, but with business taking the place of migrants as the chief evil. They agree with the right-wing populists about elites, though for the left the elites are the wealthy, while for the right they’re the liberals.

According to Blair, this populist leftism is “a profound error” that has “no chance of matching the populist appeal of the right” and “dangerously validates some of the right’s arguments.”

These columns, in their different ways, expose the fallacies of a liberalism that still is very uncomfortable sharing a tent with what is viewed as the leftist rabble. Wolcott seems primarily concerned with a strain of illiberalism—e.g., an intolerance for certain kinds of speech, an antipathy toward the compromises inherent in government—that is prevalent in isolated quarters of the left. Blair is positing a more dangerous idea: that liberalism should essentially reorient itself as a globalized technocracy, in opposition to anti-elite populism.

The first problem with these kinds of arguments is that the “alt-left” doesn’t actually exist, at least not in the way that the left’s opponents would have it. As The New Republic’s Sarah Jones pointed out, the alt-right’s goal, shared by neo-Nazis like Richard Spencer and the White House’s infamous Steves (Bannon and Miller), is to implement a white supremacist state. In contrast, the goals of the “alt-left” are not too different from that of a New Deal Democrat. Universal health care and a $15 minimum wage are not the left’s version of a Muslim ban, even if the rhetoric of the left is combative, uncompromising, and, yes, sometimes obnoxious.

As Eric Levitz points out at New York, one of the main problems with Wolcott’s piece is that he cherry-picks a number of voices—many of whom barely intersect—to speak for a perceived group. Among them are a few writers he apparently dislikes (Michael Tracey, Freddie deBoer, Connor Kilpatrick), Susan Sarandon, Mickey Kaus, and … Oliver Stone. While criticisms can be made of many of Wolcott’s targets, to lump them together as representative of the “alt-left” is nonsensical. It conflates being Loud Online with actual politics. And crucially, unlike members of the alt-right, who are being actively wooed by the GOP, these people have almost no power.

A graver sin is the adoption of a term that was created by conservatives to smear the left and discredit criticisms of the growing clout of the racist right. Richard Spencer coined the term “alt-right” for his own movement. In very stark contrast, “alt-left” is a strawman invention of far-right websites. As The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake pointed out in December, “The difference between alt-right and alt-left is that one of them was coined by the people who comprise the movement and whose movement is clearly ascendant; the other was coined by its opponents and doesn’t actually have any subscribers.” When “alt-left” is deployed by the likes of Sean Hannity on Fox News, it is a form of propaganda used to conflate groups like Black Lives Matter with the Ku Klux Klan. For Wolcott to ascribe to this notion only gives this right-wing smear more credence.

Blair invokes the specter of a “dangerous” left for different reasons. By equating the populist left’s hostility toward big business and the 1 percent with the populist right’s hostility toward migrants and people of color, he is creating a false equivalence that undermines progressivism as a whole. The ultra-wealthy patrons of the Republican Party (and, to a lesser extent, the Democratic Party) are, in fact, much to blame for deep inequality we see in the United States. Globalization did gouge the working and middle classes in the West, most notoriously during the Great Recession, even as it lifted millions out of poverty in other parts of the world. Political elites did fail us, from the Iraq War to the financial crisis.

Yet this is how Blair frames the debate over these issues:

Today, a distinction that often matters more than traditional right and left is open vs. closed. The open-minded see globalization as an opportunity but one with challenges that should be mitigated; the closed-minded see the outside world as a threat. This distinction crosses traditional party lines and thus has no organizing base, no natural channel for representation in electoral politics.

The last half of Blair’s op-ed argues for achieving “radical change” by reaching for voters who remain in the “big space in the center.” Tellingly, he calls for an alliance between Silicon Valley—an industry of socially liberal economic elites—and public policy. In his closing line, Blair states that “we must build a new coalition that is popular, not populist.”

There are two ironies in Blair’s column. The first is that Blair himself was partly responsible for his Labour Party losing a large chunk of its core working-class voters, thanks to the Iraq War and the Great Recession. The second is that huge pillars of Blair’s British-style “moderate” liberalism—such as universal health care—are totally in line with what the American populist left is demanding. The populist left, in other words, is well within the mainstream of Western democratic tradition; it is apparently their anti-elitist rhetoric that really rubs Blair the wrong way. He is, after all, an elite himself.

One big lesson from Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump was her campaign’s over-reliance on the mythical moderate voter. (Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer encapsulated this line of thinking in an infamously bad projection: “For every blue-collar Democrat we will lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two or three moderate Republicans in the suburbs of Philadelphia.” It didn’t quite work out that way.) Wolcott and Blair do not address this problem. In different ways, they make a case for “the center” based on a bad-faith argument that the populist left is the same brand of scourge as the nationalist right.

In American politics at least, the political center is the space between a functional liberal democratic party and one hijacked by white nationalists. This is not a promising ground on which liberals can build “out from,” as Blair puts it. Whether he likes it or not, the case remains that the Democratic Party will need its left wing to mobilize working-class and young, progressive voters; the left will need institutions like the Democratic Party if it wants to win elections. Over the next few years, there will be time for arguments over strategies and priorities. But there is no time for liberals to try to delegitimize the populist left; it will only cut their own legs out from under them.