As climate scientists go, Wally Broecker is famous. The 85-year-old geochemist and Columbia University professor not only coined the term “global warming,” but was one of the first researchers to accurately predict how much the Earth’s temperature would change because of fossil fuel burning. He discovered the Ocean Conveyor Belt, which moves water around the globe, and figured out that those currents help regulate the global climate. “He has singlehandedly pushed more understanding than probably anybody in our field,” one colleague said in a 2012 profile.

But many of Broecker’s colleagues don’t know that the man known as “the grandfather of climate science” once served as the chief scientific advisor to a man known for running a far-right website that publishes countless articles calling climate science a conspiracy and a hoax: Steve Bannon, the former executive chairman of Breitbart and currently President Donald Trump’s chief strategist.

“He was an intense guy,” Broecker told the New Republic in a phone interview. “I actually kinda liked him.”

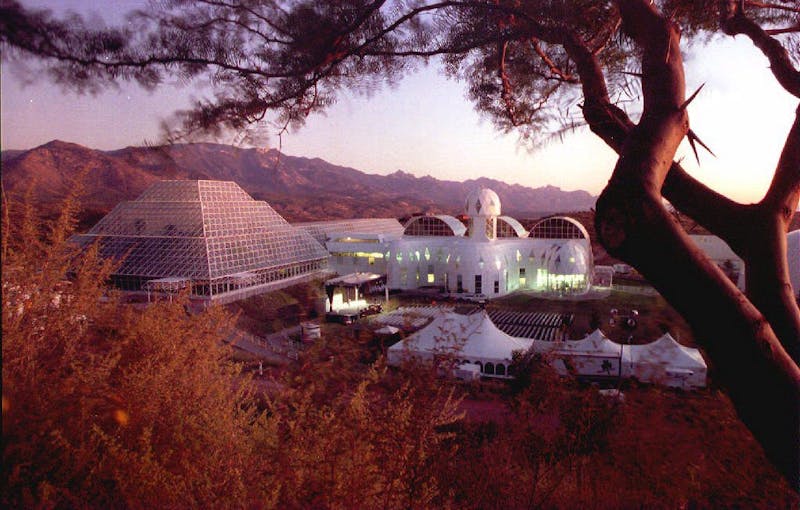

They worked together on a project called Biosphere 2, a grandiose experiment in building an artificial world. In 1993, Bannon became acting CEO of the $200 million scientific research facility in Arizona, which Bannon once described as a laboratory for observing the future effects of human-caused climate change. At the time, he boasted about Biosphere 2 scientists’ ability “to study and monitor the impact of enhanced CO2 and other greenhouse gases on humans, plants, and animals.”

“He knew what we were doing, and knew we were worried about the consequences of global warming,” said Broecker, who managed and directed Biosphere 2’s scientific operations from Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. But Bannon never publicly questioned the science during his time at Biosphere 2, and Broecker never thought twice about it—that is until years later, when he read in the paper that Bannon would be Trump’s right-hand man.

Reading up on Bannon’s politics, Broecker began to worry that Bannon might not understand the scientific consensus on climate change. So he contacted Bannon’s brother, Chris, who still works at Biosphere 2, and asked him to pass along a paper Broecker had written about how to solve the climate crisis. “Chris said he’d pass it along, and I’m sure he did,” Broecker said. “But I never heard back.”

Trump’s cabinet is full of contenders as America’s most dangerous climate villain. EPA administrator Scott Pruitt, after all, has alarmingly close ties to the fossil fuel industry, and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson used to run Exxon Mobil, the largest oil company in the world. But so far, both Pruitt and Tillerson have pushed back against some of Trump’s more anti-environment policies. Bannon has not; in fact, he appears to be the one pushing them forward.

Bannon is reportedly leading the effort to convince Trump to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement, the 194-nation accord that world leaders have described as “the best chance we have” at saving humankind from catastrophic global warming. According to The New York Times, he is also fighting more sensible forces within the White House—namely, Ivanka Trump and Tillerson—who want the U.S. to keep its climate promises. And with Bannon by his side, Trump reportedly plans to gut carbon emission regulations, slash funding for America’s main climate change research agency, and revitalize the high-emitting coal industry.

This seems a far cry from the days when Bannon was working with highly respected scientists on a project to prepare the world for the effects of man-made climate change. So what happened between then and now?

Bannon hasn’t said much publicly on climate change. His rare comments suggest not a deep rejection of the science itself, but that he doesn’t consider it a pressing issue. In a 2010 interview with Sean Hannity, he implored people to concentrate on the national debt rather than “the manufactured crisis” of global warming. In 2015, he asked then-candidate Trump to essentially choose between fighting climate change and ISIS. And amid an international celebration of Earth Hour in 2015, Bannon implied climate activists were against electricity. “These folks want everywhere to be North Korea all the time, dark and dreary,” he said.

If Bannon is a climate conspiracy theorist, he wasn’t always—at least not openly. “It certainly wasn’t clear that he was against climate research or climate mitigation,” said Bruno Marino, an isotopic chemist who was the scientific director at Biosphere 2 from 1994 to 1996. In fact, Marino said, Bannon “seemed intellectually intrigued by the broader issues we were studying,” which included the effects of global warming and increased carbon in the atmosphere.

But Breitbart’s most notorious climate conspiracy theorist, James Delingpole, considers Bannon a fellow traveler today. In a piece for the conservative Spectator magazine following Trump’s election, Delingpole wrote about how thrilled he was that Bannon would be at the helm of America’s climate policies. “One of his pet peeves is the great climate-change con,” Delingpole wrote. “It’s partly why he recruited a notorious skeptic like myself.” He insisted Trump’s disbelief in the science was real, and that Bannon would help turn it into action. Trump’s climate denial was “not some wind-up stunt to troll lefties,” Delingpole wrote. “It’s going to be a core part of his administration’s political program.”

Not everyone at Breitbart believed Bannon really cared about climate change, though. One former reporter, who asked not to be named, said that while Bannon would go on rants in the newsroom about issues like immigration and national security, climate change was never a topic of interest—aside from when Senator Bernie Sanders would compare the threat of climate change to the threat of terrorism. Bannon knew such articles would rile up Breitbart’s readers and get lots of clicks.

Whether he cared or not, Bannon allowed salacious and often misleading climate stories to populate the site. “The content tells you everything you need to know,” said Kurt Bardella, Breitbart’s former spokesman. “Breitbart overall was against climate change. Any time there was a weather event, they’d be the first to mock anyone who blamed it on climate change. If it was cold when it was supposed to be warm, they’d be the first to make fun of global warming.”

Marino suspects Bannon could be willfully ignoring his knowledge of climate science. After all, Bannon was at the helm of a climate-centric project that—while plagued by scientific mishaps, drama, and debt—was spearheaded by brilliant researchers from across the globe. Bannon wasn’t involved in the scientific process at Biosphere 2, but Marino said he clearly knew the basics.

“The biggest factor when I think about Steve is, how could he not have brought with him today something of what he learned then? That doesn’t compute for me,” Marino said. “He must know. He must have some deeper thoughts about climate change than he’s letting on. I don’t think he’s fully opened up about what he’s learned during that period.”

If Bannon does have deeper thoughts about climate change, they could be buried in The Steam Experiment (aka The Chaos Experiment), a 2008 film on which Bannon was an executive producer. The film, according to its promotional text, depicts “a disgraced and deranged scientist (Val Kilmer)” who “traps six sexy strangers in a hotel steam bath and slowly turns up the heat.” The whole point of the movie is to “prove that humanity will go crazy under the pressures of global warming.”

Perhaps Bannon believes that a warming world could cause chaos—and even welcomes it. After all, he is an alleged Leninist who wants to deconstruct the administrative state. Or perhaps Bannon, a prolific film producer, simply thought this particular B-movie would turn a profit.

We may never know. (Bannon did not respond to our requests for comment.) But there will be chaos indeed if the U.S. halts its commitment to fighting climate change. Coastal sea level rise will cause waves of refugees across the globe. Longer, more severe droughts and heavier, extended rainfalls will threaten crop productivity, and therefore food security. A large and growing body of research suggests “more wars, civil unrest and strife, and also more violent crime in general” in a warming world.

In a Wired article in December about Bannon’s Biosphere 2 work, Marino said he hoped Bannon would have an influence on climate policy if Trump became president. Now that Trump is president, Marino’s not so sure. “At the time I thought that some of the thinking he acquired during his time at Biosphere 2 might have provided some guide,” Marino said. “But apparently it hasn’t. Or he’s not saying.”

But Marino isn’t giving up hope that the man he once knew, who used to keep books about climate science on his desk, could still help America develop real solutions for climate change.

“People should call on him to use that knowledge to come up with a better way. A way that somehow serves his nationalistic focus,” Marino said. “I would say that’s a challenge I would put to him and the administration. If you’re so brilliant, and you have all the answers, then come up with a solution. Where is it?”