The memory is vague, perhaps implanted. It may only exist because my mother has taken great pains over the years to remind me of it. It was either 1991 or ’92, and I am about three years old. It’s Christmas Day and we’re at a house in my hometown of Colrain, Massachusetts. Other people are there, too. We brought cookies to the event. At the time I thought of it as a party; I know now it was not.

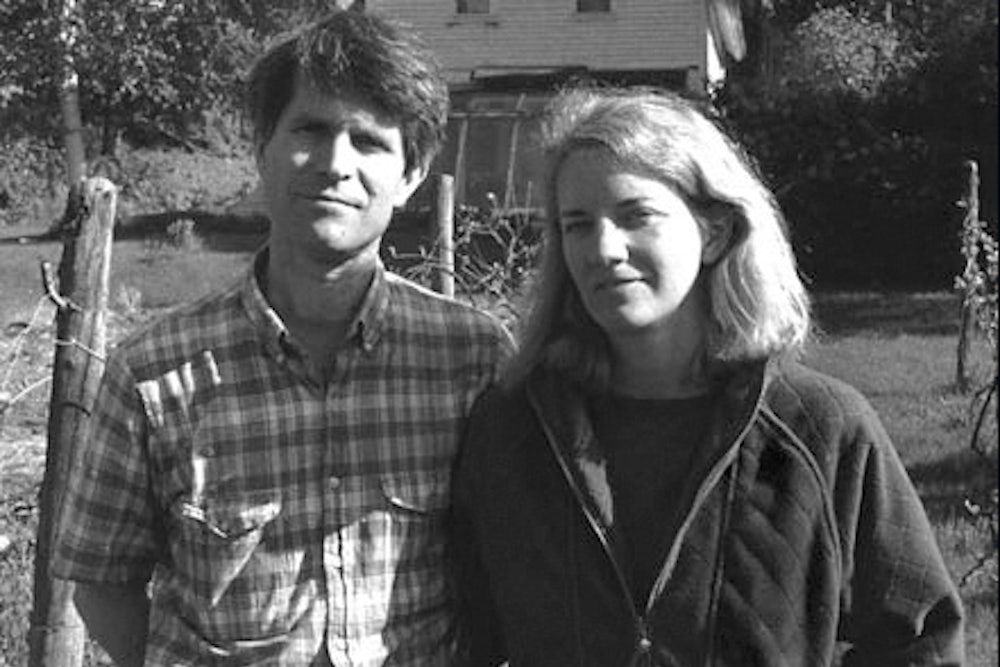

This memory was my mother’s way of telling me that I’ve always, even as a child, been politically active. We were there offering support to our neighbors, Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner. They had been war tax resisters for decades, and at this moment they were having their house repossessed by the IRS. My mother had dragged her preschool-aged son to what was essentially an act of civil disobedience.

I grew up in Western Massachusetts, in an area dubbed the Pioneer Valley—a haven for lefty politics. In the 1970s it was the training ground for the No Nukes campaign, a prominent anti–nuclear war movement. Kehler and Corner were far from the only people in the area who refused to pay war taxes. But they may be more famous than others thanks to a 1997 documentary called An Act Of Conscience, which chronicled their house’s seizure.

The movie depicts how the two lost their house and occupied it for over a year. With the help of affinity groups, who lived in or near the house, they stayed on the property while the authorities sold it and then when the new tenants attempted to move in. Numerous people featured in the movie were fixtures in my early life. They all lived together in this progressive bubble, each with their own way of following their political creed.

The movie now comes off like a relic. There’s a lot of singing and chanting; homemade waffles are made quite a few times; Pete Seeger makes an appearance, because of course; and hand-painted, slogan-filled signs are showcased. These people all followed (and likely still follow) a playbook that seems worn, almost comical. They all had a similar style of wool tops and berets. But stereotypical as they seem, the communal insistence on living a virtuous life is heartening still. There is a glint of utopian politics, one that’s hard to find now. And lately, I’ve been drawn to thinking of ways of resistance that transgress usual boundaries.

Kehler and Corner still live in Colrain. They’re still diehard pacifists too. The couple refuse to pay taxes that support war and military efforts. It started as a way to protest the Vietnam War draft, but it’s a practice with roots dating back to World War II. The argument could be made that the U.S. was founded on a kind of tax resistance.

I haven’t lived in Massachusetts for over a decade, but I speak of my hometown with pride. Growing up around progressives of a certain generation is a singular experience, one that is defined by knowing people like Kehler and Corner. They follow a lifestyle that’s hard to mimic outside of its own petri dish—and yet in our era of extremist government, there might be something to be learned from such devotion to one’s political beliefs.

Tax resisting has been around for as long as this country, though it has many connotations. When I talked to Kehler recently, he was very insistent about including the “war” descriptor. His practice comes from a deep-rooted pacifism, and is not to be confused with the ideology of libertarian-isolationists, like the Bundys, who rail against the federal government.

War tax resisting comes from a mindset that reached fever pitch in the ‘70s and ‘80s. The idea is to pay the portion of taxes that don’t go to the military and donate the rest (some keep these withheld taxes in case the IRS goes to bat against them). Since any federal tax has some toe in the military, some people, like Kehler, simply don’t pay their federal income tax and instead give it to organizations they’d prefer to see flourish. The Vietnam War originally set Kehler on his course toward refusing to support wartime activities. (He went to jail in the late ‘60s for resisting the draft.) As the years went on and the nuclear arms race got more acute, his beliefs hardened, along with a group of other anti-war activists.

The Pioneer Valley, a blob of land west of Worcester and east of the Berkshires, is one of those magical havens of ultra-progressive politics. It houses five colleges, which may have something to do with it. But it also has a history of peaceniks and revolutionaries hanging out in the area.

The people there “pursue their own vision of what a just and what an appropriate society is,” said Rob Cox, an archivist at UMass Amherst. “There’s a real deep strain of activism around moral issues.” He pointed to Shays’ Rebellion, the armed uprising in the 1780s that shaped the Constitution’s formation, which happened in the nearby town of Springfield. Many people told me that political awakening is rooted in the Valley’s water.

This fits with my own memories of the place. From the age of seven until at least twelve, I would vigil for peace with my mom. When George W. Bush launched the Iraq War, hundreds of us piled into a bus to protest in the streets of New York. In high school, I helped out at the local peace center. I followed this path both because it made intuitive sense—I mean, peace sounds like a nice thing when you’re a kid—but also because it was simply all that was around me. People like Kehler and Corner represented the depths to which you could practice what you preached.

In the documentary, narrator Martin Sheen rattles off the statistic that there are 10,000-some-odd war tax resisters in the country, and claims that the number is growing. Today, it’s hard to know the real data. Kehler admitted that interest in the practice has peaks and troughs. During the first Gulf War there was heightened appeal, much as there was during Vietnam. Ditto in the early aughts with the Iraq War. Now, however, it’s harder to figure out exactly what one should be resisting. “Back in the days you were here growing up,” he told me, “there was a higher concentration of war tax resisters than most places in the country. But it’s waned here also.” He added, “People have just gotten used to being at war, unfortunately.”

Ruth Benn, a decades-long war tax resister who is now at the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee, agrees that interest has been waning for the last decade or so. Benn lives in Brooklyn, although she did reside in the Pioneer Valley for a while, where she worked with the peace activist Frances Crow. Groups try to tally numbers about who’s doing what, she said, but there are many organizations with differing practices and some people prefer to not publicize it. “We still say about 8,000 people,” she said, “but it’s really hard to tell.”

All the same, she said there’s been marked interest in tax resistance as a form of protest. “People are interested in the Trump agenda,” she said, “not so much the war point.” Some groups have committed to not paying taxes until Trump releases his IRS returns. Her website has been getting more hits than usual, she claimed. “If anyone’s just looking up tax resistance, they’re going to find us.”

Before I began interviewing people for this article, I rewatched An Act Of Conscience. As a work of art, it suffers from conventionality. It’s a linearly told story, very cut and dry. But there are moments when the truly remarkable is captured. In one of the more uncomfortable scenes, Kehler and Corner are in their house, occupying it. The new owners—thanks to a cheap foreclosure auction—are there, too. The two couples talk, each trying to understand the other. The two war tax resisters are deliberate orators; though the emotion of the moment is palpable, they are simply trying to understand how someone in good conscience could take another’s house.

The tenants don’t have good answers, but they listen all the same. But with each moment their belief that the house belongs to them, thanks to the new deed they just signed, becomes more concrete. It’s both hard to watch and impossible to look away. Each party states their case and yet nothing is to be done. The moment ends without resolution, as does most of the movie. But Kehler and Corner’s personal resolve, even as they both remain empathetic, is at once enthralling and depressing to watch.

In calling Kehler, I realized I wanted an easy throughline showing how my upbringing could inform my current political practices. We talked for a while about his origins as a pacifist and how he approaches his resistance. As he does in the movie, he still talks cooly with intent. But I realized that my most urgent question—how should I act?—couldn’t be fully answered by him. He’s just a guy with a stiff moral backing who tries to live the best way he can.

I wanted to figure out how to convey their simple belief system to the odd moment we’re in now. When you look back at activism from the early ‘90s it’s almost quaint. The nuclear crisis seemed contained; there were individual wars to oppose. Kehler acknowledged this. He mentioned that the state of things is so convoluted and bad that it seems to eclipse the mere spectre of war. “War itself is not at the top of most activists issues,” he admitted. “There’s much more concern about the climate crisis, also the threat by Trump people to immigrants and refugees and women and gays and trans people. Those are the neediest issues.” But, he insisted that the focal point of resistance is the same. “We need to make clear,” he said, “the extent to which all these problems are related.”

“What I hope is that people do locally what makes sense to do locally,” Kehler concluded. This is a common trope among those I grew up around—people trying to make change from within. Living in a cocoon of like minds makes this easier. The Pioneer Valley is a place, said Cox, where these practices are “allowed to flourish where it might not in other areas.” Maybe that’s why Kehler and Corner are of interest to me. They were practicing their politics in a safe environment, yet they were still put to the test. I should add that they ultimately persevered. In the end of the film, they get their house back in an 11th-hour deus ex machina.

Toward the end of the movie, there’s one other moment that stands out. Kehler and Corner stand in front of a group in an old church; they’ve been occupying the house for over two years but they fear they are on the verge of being kicked out. They’ve been arrested, as have their friends. Many are exasperated, want to stop. The end doesn’t seem in sight. Others demand to continue fighting and occupying the house. Kehler and Corner are tired. They have no answers and don’t know what’s going to happen next.

I wanted to ask Kehler about this fatigue and desperation, but I didn’t know how best to approach it. Instead, I asked about what people can do now, even if war isn’t their main priority. The answer he gave is simple, what one would expect from an activist and pacifist. Do what you can and figure out ways to show solidarity. That’s the ethos, I suppose, of where I grew up. But that scene’s sadness is closer to what I’ve been feeling of late. The only difference is that is there is no deus ex machina in the offing.