Like many people around the world, Yale historian Timothy Snyder responded to the election of Donald Trump by fuming on social media. “Americans are no wiser than the Europeans who saw democracy yield to fascism, Nazism, or communism,” he lamented in a Facebook post on November 15. Drawing on his field of expertise—Europe in the era of Stalin and Hitler—Snyder went on to offer 20 “lessons” for how to resist a dictatorship. His post went viral, amassing more than 13,000 likes. He has now expanded that post into On Tyranny, a curious mixture of historical anecdotes and self-help bromides, premised on the idea that America is at the dawn of a tyrannical age, and that the past offers clues for resistance.

The ominous overtones of his project closely match the public mood of recent months. After Trump’s win, dystopian novels like George Orwell’s 1984 and Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here sprang to the top of best-seller lists, and Americans discovered a newfound interest in theorists of dictatorship and authoritarianism. Warning of NSA surveillance, Snyder reminds us that Hannah Arendt, who fled Nazi Germany, defined totalitarianism as “the erasure of the difference between private and public life.” In The New Yorker, Alex Ross argued that “the Frankfurt School knew Trump was coming.” Arendt and Theodor Adorno are now discussed not as relics of the last century and its horrors, but as seers whose works speak afresh to our moment.

Nor is Snyder the first commentator to compare Trump’s America directly to the twentieth century’s most oppressive regimes. For months before the election, writers at Vox, The Atlantic, and Slate debated whether the president could truly be deemed a fascist. In September, New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani reviewed a biography of Hitler, emphasizing his Trump-like qualities: Without mentioning Trump himself, she evoked a “pathetic dunderhead” of a leader with a “big mouth.”

These comparisons with history’s darkest moments are deliberately drastic; their powerful emotional resonance is called on to reflect the disturbing nature of Trump’s victory. For many, his rise defies a certain conception of Americanness: World War II and the Cold War, the two existentially threatening events of the previous century, determined the types of society America opposed and defined itself against. Only in those societies, so the thinking goes, could the abuses Trump proposes have been carried out, and only from those other societies could we learn how to resist him. This version of history assures us there is no need to look too deeply into America’s own past for the origins of an authoritarian president or his supporters. To liken Trumpism to Nazism is to lament, somewhat helplessly, that we are becoming as bad as the forces we once fought.

On Tyranny starts from a salutary impulse. Snyder is right to think that the discipline of history has special value in strengthening democracy and combating authoritarianism. Too many academic historians suffer from the vice of antiquarianism. Having a narrow focus on describing the particularity of the past, they resist linking their research to today’s most pressing issues. University-based historians, in fact, are prone to see “presentism”—the active drawing of connections between the past and present—as antithetical to true scholarship. But historical consciousness, no less than the scientific method or philosophical reasoning, is a mode of thinking with practical applications. As history involves trying to figure out the minds of those who lived in a very different time, it fosters intellectual empathy. And the forensic scrutiny that historians apply to evaluating historical documents is an invaluable skill for recognizing propaganda and “fake news.”

Snyder is superbly positioned to bring historical thinking to bear on the current political scene. A prolific scholar and proficient writer, he’s written powerful books on the Soviet Union, Hitler’s Germany, nationalism, and the Holocaust, each of which has accomplished the rare feat of winning both a large popular audience and the respect of his peers. The book that Snyder and the late Tony Judt collaborated on, Thinking the Twentieth Century, demonstrates the power of the historical imagination as a tool of social analysis. In that book, Judt warns of an “American nationalism” based on “the politics of fear”—an eerily exact forecast of the rise of Trump and other demagogues.

It’s also commendable that in On Tyranny, Snyder counsels taking action rather than merely taking refuge in historical comparison. His Facebook post, and now the book, includes the recommendation to “stand out.” He reasons: “Someone has to. It is easy to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different.” These unpretentious words remind us that political resistance isn’t a matter of action-movie heroics, but starts from a willingness to break from social expectations, as Rosa Parks did when she refused to go to the back of the bus. And Snyder’s advice to “be calm when the unthinkable arrives” is undoubtedly wise:

Modern tyranny is terror management. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power. The sudden disaster that requires the end of checks and balances, the dissolution of opposition parties, the suspension of freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial, and so on, is the oldest trick in the Hitlerian book.

Yet many of the directives Snyder urges on his readers are a little vague and mystifying. There is a strange disjunction between the gravity of the situation Snyder warns against (Hitler-style tyranny) and the banality of his advice. His recommendations range from the Zen-like (“Believe in truth”) to the nationalistic (“Be a patriot”). There’s no clear guiding principle behind each of them. “Read books,” Snyder suggests. OK, sure—reading is always good. But after listing off the familiar classics of anti-totalitarianism by Orwell and Milan Kundera, Snyder adds a more recent work: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, which he presents as a novel “known by millions of young Americans that offers an account of tyranny and resistance.” Snyder counsels, “If you or your friends or your children did not read it that way the first time, then it bears reading again.” While it makes sense to meet people where they live, the hero in a moral tale will always win, especially when he has a talent for magic on his side. Political realities, by contrast, call for specific strategies.

Considering that this volume started as a Facebook post, Snyder’s ninth rule—“Make an effort to separate yourself from the internet”—is perhaps the most puzzling. He is wary of the internet partly because it can be used to spread false information, and partly because it could allow a dictator to gather information about his or her subjects. “Nastier rulers will use what they know about you to push you around,” Snyder writes. “Remember that email is skywriting. Consider using alternative forms of the internet, or simply using it less.” This feels like an oddly antiquated view of the digital tools at our disposal. Yes, those tools can be used as weapons against us (just as print can be used to spread fake news, and telephones can be used to collect data on behalf of an aspiring tyrant). But Snyder makes no mention of the potential of the internet for resistance, or the fact that activists used social media to summon thousands to protests at airports and courthouses in the first days of Trump’s administration.

Much of Snyder’s advice is not, in fact, aimed at actively opposing tyranny. Few of his rules will help citizens oppose the use of torture in the war on terrorism, or restrictions on immigration from predominantly Muslim countries, or even a transgression as simple as the president’s use of Twitter to bully judges, journalists, and businesses that defy his authority. His rules are mostly aimed at ways to protect oneself from the punishment of a regime—a necessary and laudable goal, but one insufficient to creating an effective mass resistance. If Martin Luther King Jr. had heeded the self-help advice of On Tyranny, there might have been no “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.”

Snyder’s advice to Americans is, he tells us, based on his study of repressive regimes. Yet he never explains exactly how he thinks the experience of an American today is comparable to the experience of a Russian in the Soviet Union or a German living under the Third Reich. Nor does he look too closely at the ways these regimes resemble—or do not resemble—one another.

A tendency to lump together many disparate historical phenomena lies at the core of On Tyranny, as Snyder strains to apply the term “tyranny” to a huge variety of political problems. Tyranny is, he tells us, “the circumvention of law by rulers for their own benefit.” Hitler and Stalin were tyrants. But American society has also seen tyranny “over slaves and women, for example.” These two examples of tyranny in action are not alike at all: In one case we are talking about political leaders; in the other, we have entrenched social systems, instigated by no single person. This broad usage of the term renders it virtually meaningless. The injustices imposed by the will of a tyrant belong to a different category than those suffered by slaves (at the hands of not just their masters but white society) or by women (at the hands of men). These last were inequities deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life.

Historical analogies are tools if they are used carefully; when they come too easily, they can be dangerous. To compare Trump to Hitler and Stalin rather than to Barry Goldwater, George Wallace, and Ronald Reagan is to nurture a reassuring myth that Trump is un-American. This is a consoling fantasy, since it implies that Trump doesn’t have deep roots in the American experience; if we simply get rid of Trump, all will be well. It’s a way of turning the current political tragedy into a fairy tale, in which a scary monster threatens us, but once he is quickly vanquished, normality is restored, as if it had all been a bad dream.

In truth, there is nothing foreign or even original about Trump’s politics. America is not just the land of immigrants but also the land of nativism, a worldview that the children and grandchildren of immigrants often adopt as a way of moving up the social ladder themselves. Trump’s father was arrested at a Ku Klux Klan march and, in his career as a landlord, he was sued by the government for discriminating against black people. Beyond his family heritage, Trump came of age in a period when politicians in both the South and North rose to power on the backlash against the civil rights movement.

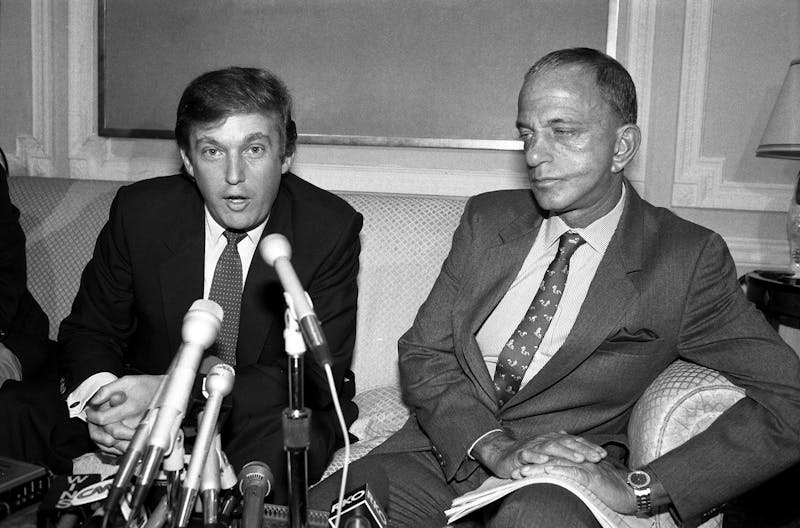

From George Wallace and Richard Nixon, Trump learned the language of “law and order” as a racist dog whistle; from Charles Lindbergh, the popularity of the slogan “America First”; from his mentor Roy Cohn, the effectiveness of smearing opponents; from General George Patton—or the version of him in the George C. Scott film—the appeal of roughneck militarism; from Ross Perot, the potency of complaining about free trade and freeloading allies; from Pat Buchanan, the strength of nativism. In sum, Trump’s ideology is not something new, but the repackaging of older forms of American xenophobia and authoritarianism.

This American authoritarianism, as befits a geographically dispersed society with a meager social security net, is less concerned with building up an all-encompassing state than its European counterparts. American authoritarians have rarely gone in for paramilitary movements, perhaps feeling that the local police and national guards can be relied on to enforce their agenda. And Trump’s promises of bringing back factory and mining jobs are much less extravagant than the Nazi agenda to build a strenuous and athletic master race. If Trump is a fascist, he’s a fascist befitting a nation of couch potatoes who want to be left alone, not to embody the Triumph of the Will.

For most of the last century, American authoritarian impulses have been powerful but never really dominant. Lindbergh, after all, was discredited by Roosevelt; Patton was sidelined by General George Marshall; and McCarthyism was eventually checked by the Eisenhower administration. Nixon did become president, but he felt compelled by the office to hide his dictatorial tendencies, using them covertly in ratfucking operations against his opponents, which ultimately led to his disgrace and downfall. The only new thing about Trump is that for the first time, the authoritarian wing of American politics has stepped into power undisguised and unashamed.

Snyder’s preferred word, tyranny, has ancient origins. It’s a curiously static, ahistorical and depoliticized term, coined before the age of mass politics. Tyrants like Caligula didn’t need ideologies or energized political movements. As such, Snyder sees no need to explore the ideological contents of Trumpism. Unfortunately, this means Snyder has no political answers to Trumpism. He doesn’t discuss the need to mobilize the constituencies most likely to fuel a countermovement—women and people of color—or to win over the white working class. Aside from a smart paragraph about marching, Snyder has nothing useful to say about such democratic resistance.

If Americans are to fight Trump, however, the best models are not the tactics used by dissidents to fight the police states of Stalin and Hitler, but rather the techniques used by earlier activists working within the American system. Soviet dissidents, in a state built on tight censorship, relied on samizdats; today, in a landscape of overabundant online media, such underground publications seem unnecessary. Conversely, Americans have long found in the courts a bulwark against authoritarianism, which continues in the ACLU’s successful efforts to get a stay on Trump’s executive order on immigration. The techniques used by the NAACP to fight the Klan, by the ACLU to fight McCarthyism, and by The Washington Post to fight Nixon—political organizing, litigation, and investigative journalism—are still essential.

The best part of On Tyranny is the epilogue, a thoughtful meditation on the fate of history in our moment. Snyder connects Trump’s rise to the deeply ingrained belief among elites that history had ended. Triumphant after the close of the Cold War, Americans luxuriated in a fantasy that they lived in a perfected polity, an illusion that withstood even the ruptures of September 11 and the global economic meltdown in 2008. Believing “that there was nothing in the future but more of the same,” Americans came to feel, in Snyder’s words, that “history was no longer relevant.”

Now history has resumed with a vengeance. With each passing day, the course of events threatens national institutions and stability as it has not for many decades. “Our government continues to be in unbelievable turmoil,” General Tony Thomas, who serves as head of U.S. Special Operations Command, told a military conference in Maryland in early February. “I hope they sort it out soon, because we’re a nation at war.” Although Trump himself has only a shallow historical consciousness, his legacy may be to teach an entire nation the full import of Faulkner’s words from Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.”