A friend of mine has a favorite question. A local union organizer, he poses this question when he encounters people who won’t participate in the labor movement for reasons of ideological purity. They can’t go to the march, or sign the petition, or talk to their fellow workers, they will explain, because the movement doesn’t perfectly reflect all of their political beliefs, all of the time. In these instances, my friend asks: “Do you want to feel good about yourself, or do you want to win?”

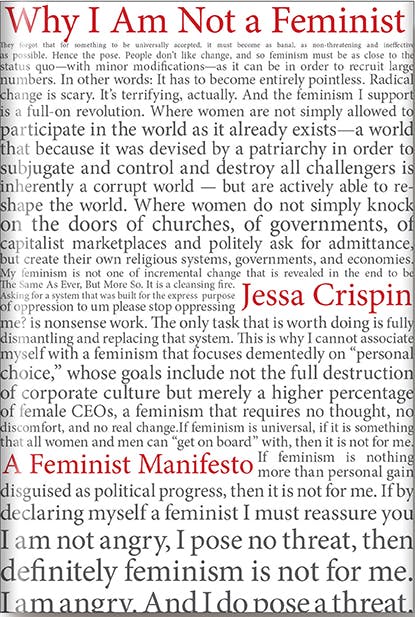

I found myself wanting to put this question to Jessa Crispin many times while reading her perceptive and impassioned new book, Why I Am Not a Feminist: A Feminist Manifesto. A critique of contemporary feminism, the book began, as so many books do, one drunken night in New York City. Crispin spent an evening ranting to the publishers of Melville House about how feminism had lost its way. It was now either entirely toothless, or fixated on the wrong problems: “safe spaces,” “outrage culture,” and “lean-in culture,” as she would later tell Vulture. Self-proclaimed feminists were so worried about learning how to negotiate raises and project confidence that they weren’t willing to challenge oppression in any meaningful way. Instead, they took to Twitter to police speech and to commiserate over their so-called “wounds.” They cared more about a joke made in poor taste than they did about sweatshops or deforestation.

At its best, the resulting manifesto serves as a useful skewering of feminism’s worst tendencies. In her introduction, Crispin rejects the “feminist label” because it has become almost meaningless. In a chapter titled “Women Do Not Have to Be Feminists,” Crispin pokes holes in the ideal of female independence, correctly pointing out how often it leaves women stranded, overworked, and underpaid. Moreover, as she laments, the term “feminist” has come to be used so broadly that it can apply merely to any prominent, successful woman, rather than one who consciously questions the patriarchy. We now measure feminism’s success by the triumphs of female CEOs and self-declared feminist pop stars.

Over the course of the book, it becomes clear that Crispin is denouncing a particular strain of contemporary feminism: what she alternately calls “surface-level feminism” and “universal feminism.” We might also call it “neoliberal feminism.” This is a feminism preoccupied with workplace success and equal earnings, a feminism that abets global capitalism rather than challenging it. To many feminists, neoliberal feminism is a kind of “faux feminism”: It represents the interests of the top 1 percent of women while ignoring, or even exacerbating, the challenges most women face. As the political theorist Nancy Fraser has argued, a woman working in the corporate world can “lean in” only if she can also “lean on” low-wage workers—usually women of color—who will care for her children, clean her home, and cook her food.

Crispin warns, too, of the ways that feminism and capitalism can be mutually reinforcing. Early in her book, she makes clear that she will not be part of any feminist movement that is not about “the full destruction of corporate culture.” She calls her feminism a “cleansing fire.” She doesn’t want to infiltrate the halls of power; she wants to burn the very buildings to the ground. The more people pour into the movement, the more Crispin wants to retreat. “If feminism is universal,” she writes, “if it is something that all women and men can ‘get on board’ with, then it is not for me.”

Crispin has long positioned herself as an outsider. In 2002, she founded one of the first online literary reviews, Bookslut, in an effort to cover idiosyncratic and innovative writers who rarely garnered mainstream critical attention. The result was a wider range of reviews and, often, more honest reviewing. Her first book, The Dead Ladies Project, was a travel memoir in which she visited European cities—Berlin, Galway, Sarajevo—and mused on the work of writers such as William James and Rebecca West. Many of these figures served as foils to the author herself: Jean Rhys was needy, but Crispin is independent; West was unselfconscious, but Crispin is self-aware. She wouldn’t make the same mistakes.

Crispin’s stance in Why I Am Not a Feminist fits with this outsider mentality. Her main objection to contemporary feminism seems to be that it is popular. To her mind, if a social movement is popular, then it must necessarily be “banal … nonthreatening, and ineffective.” She hates the idea that feminism has “become universal,” as if a movement’s growth were a hindrance to its success. By her account, feminism has always been a “fringe movement,” one that appealed to some but that alienated and threatened many others. She is thus suspicious of feminists who want to “convert” others to their cause. (In some circles, this is called organizing.) She wants feminism to stay true to its radical origins, to create its “own religious systems, governments, and economies” rather than to “knock on the doors” of established institutions.

There’s something decidedly appealing, even romantic, about this vision of a radical movement that will, in Crispin’s words, set about “fully dismantling” the system. The feminists of the 1960s and 1970s, Crispin believes, brooked no compromise in challenging the patriarchy and, though the rest of us benefit from the bravery of these few, their legacy has been unjustly neglected. Younger women have lampooned the anti-pornography feminists Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon, painting them as “bra-burning, hairy-armpitted” bogeywomen. But Crispin celebrates their anger, their willingness to displease and even disgust. She seems to yearn to return to this historical moment, when sisterhood was powerful and feminism was fierce. She likes that these women “went too far.”

The problem with Crispin’s vision is twofold: It misconstrues feminism’s past, and thus offers the wrong prescription for the present. For starters, the last decade has seen renewed interest in the art and thought of many radical feminists, including those Crispin name-checks. Shulamith Firestone, who called pregnancy “barbaric,” was memorialized at length in the New Yorker and n+1 after her death in August 2012. Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, a groundbreaking work of feminist literary criticism, is back in print. Even Yale University, not usually a bastion of radical politics, recently named one of its new colleges in honor of Pauli Murray, the civil rights activist and founding member of the National Organization for Women.

What’s more, there was as much ideological variation within second-wave feminism, and even within radical feminism, as there is in the feminist movement today. The radical feminist groups Redstockings, Cell 16, The Feminists, and New York Radical Feminists disagreed sharply about sexuality, psychology, and hierarchy. Were married women “brainwashed,” or were they making strategic economic decisions? Should feminist organizations have formal leadership structures, or should they be horizontal and leaderless? Must all women become lesbians? Margaret Sloan, June Jordan, and Alice Walker criticized the whiteness of second-wave feminism and the exclusionary editorial practices of Ms. magazine; Firestone, Ellen Willis, and Kathie Sarachild fought as bitterly about movement tactics and strategy as Crispin might fight with her contemporaries today.

By missing this history of conflict and coalition-building, Crispin implies that one should only participate in a movement when it mirrors your own beliefs—beliefs you’ve already formed. Some of her objections to “universal feminism” reminded me of the important critiques of the recent Women’s March—it was too white and too polite—but she doesn’t recognize possible allies. Reading Crispin, one might think that the right thing to do on January 21 wasn’t to show up and speak out, or use the march as an opportunity to engage and organize the potentially like-minded but politically naïve, but rather to do nothing at all.

Within today’s feminist movement, moreover, Crispin would find many women who share her criticisms of “universal feminism.” Feminism must be anti-capitalist, Crispin argues. It must be intersectional. It must work for the betterment of all humans, not just women. These are the same arguments that Angela Davis made at the Women’s March when she called on protesters to join “the resistance to racism, to Islamophobia, to anti-Semitism, to misogyny, to capitalist exploitation.”

Though Crispin doesn’t come out as a socialist feminist, many of her ideas for change mark her as such. She believes we need better social welfare programs and redistribution of wealth. Since everyone living under global capitalism, she reasons, lives precariously, increased job security and social benefits will help more women more profoundly than any initiative designed to benefit female executives. Crispin points out that second-wave women were right to liberate themselves from unpaid care work, but we now face a situation where care is in desperately short supply. This echoes arguments Fraser has been making for decades: A capitalist society can produce all the wealth it wants, but it will fall apart if it doesn’t find ways to look after the young, the sick, and the old. Such concerns make Crispin part of a growing community of feminists, rather than the outsider she perceives herself to be.

Indeed, I was puzzled by Crispin’s insistence that none of today’s feminists share her aims. I thought of the women behind Black Lives Matter, and the women risking injury by protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline. I thought of the female service workers leading today’s labor movement in the Fight for $15 and in organizing the hotel industry in Nevada. They represent the kind of intersectional feminism that helps women by helping the economically oppressed, the environmentally at-risk, the silenced and the marginalized. They are proof that today’s feminist movement includes many more women than Sheryl Sandberg and Taylor Swift.

It may be easier to adopt the feminist “label” today than it was in the early 1960s. Still, we need more women to claim feminism, and then fight to make the movement what they want it to be. As a movement grows, internal disagreement grows, too. This isn’t always a bad thing: It is often in moments of disagreement that participants find common goals, fashion livable compromise, or persuade moderates that more radical strategy is needed. Living with conflict, building coalition—this is the stuff of politics. As the threats to feminism grow ever more apparent, I hope Crispin will stay in the fight.