The private thoughts of Donald Trump are largely unknowable to the people he governs, but his sports allegiances are quite evident. He likes winners, and the greatest winners in professional athletics today are the New England Patriots. This Sunday, while the harried mothers of Massachusetts and Rhode Island stir crab dip, the president will be pulling for Tom Brady and Bill Belichick’s dynastic team to defeat the Atlanta Falcons in Super Bowl 51 (sorry, those Roman numerals are too fatuous for me). In a game between teams with no meaningful history or player rivalries, Trump’s oft-stated support for the Patriots has become the inescapable pregame narrative.

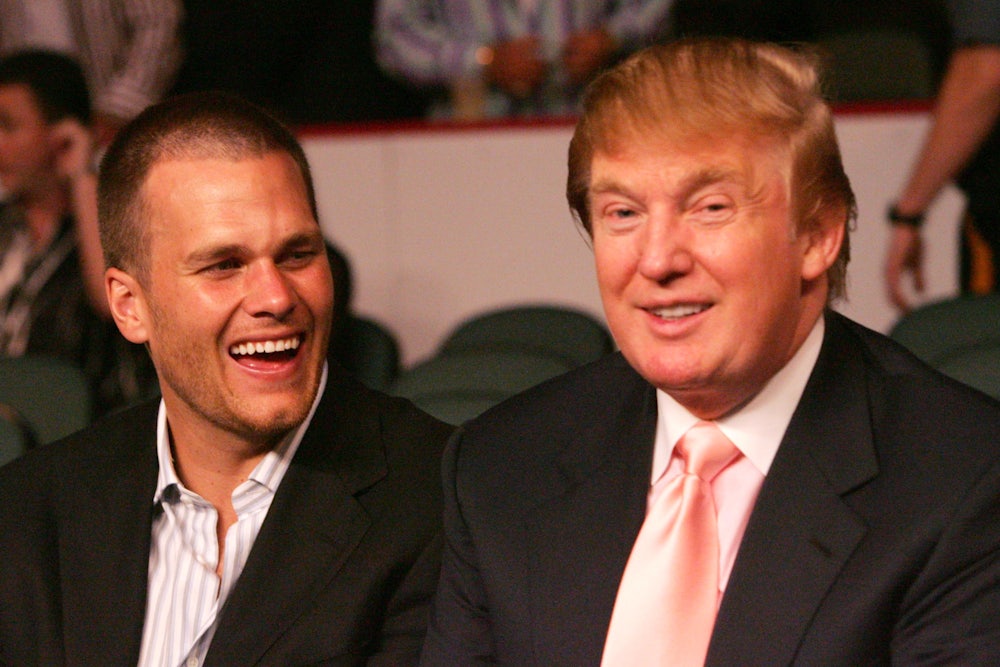

What accounts for the intuitive pairing of our most powerful leader with our most undeniable champions? The media has a theory. The Patriots are seen as Trump’s gridiron emissaries because of the much-discussed relationships between the president and the team’s three pillars: Brady, Belichick, and owner Bob Kraft. These ties have provoked a backlash throughout deep-blue New England, breeding what SB Nation’s Charlotte Wilder dubs a “Trump problem.” The New York Times Magazine’s Mark Leibovich, who has chronicled Brady’s dietary habits with the same scrutiny that he applied to Washington’s political culture, has observed an “uncomfortable love affair” between the team and its most reviled devotee.

This is the simplest explanation of the Trump-Patriots nexus, and the least satisfying. While the personal connections between Trump and the Patriots troika are somewhat remarkable, given that he is sometimes described as having no friends, it’s also worth asking how deep they truly run.

Brady raised some hackles in 2015 by wearing a “Make America Great Again” hat, but the whole of his career has been as anodyne and consumerist as Michael Jordan’s; if he ever entertained a thought about anything besides defensive alignments and UGG sales figures, he’s kept it to himself. Belichick’s affection for Trump seems more deeply rooted, but when pressed by the media, he denied that it was politically motivated and compared it to his acquaintance with John Kerry. Bob Kraft, a Massachusetts institution who contributes generously to Democratic causes and candidates, has spoken expansively of his friendship with Trump, but paints it as a typical mingling of the galactically rich. Trump apparently took great care consoling Kraft after his wife died in 2011, and Kraft returned the favor by attending an inaugural gala. Beyond the obvious utility of having the president’s personal phone number, there’s no evidence of any political affinity or cooperation between the two.

The obvious, superficial similarities between Trump and the Patriots also disguise some revealing differences. It’s true that both have ascended to the peak of their respective endeavors, earning cultish followings as they climbed, and both have inspired a media fixation bordering on the obsessive. But every lie that Trump tells about himself is actually true of the Patriots. If his performance as an executive—shot through with bankruptcy and litigation—had a professional football equivalent, it would be closer to the Cincinnati Bengals than Belichick’s winning machine. Trump claims that the political system is rigged against him? The NFL literally takes steps to undermine powerhouse teams, sticking them with tougher opponents and less talented rookies. And if the president is actually hounded by nefarious elites, I’d like to know how they compare to NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, who has waged a two-year campaign of vindictiveness against Brady following the inane “Deflategate” scandal.

Viewed from afar, however, their metaphysical positioning is the same. Whichever route they took to the top—whether by race-baiting and the Electoral College in Trump’s case, or psychotic preparation and creative payroll maneuvers in the Patriots’—they now stand there together. And they share one more thing in common: While both have vanquished their opponents and brought ecstasy to their partisans, they’ve done so without gaining wider admiration. This is why it feels natural to couple the president, America’s least favorite politician, with the Patriots, America’s least favorite team.

Their shared unpopularity is a paradox. Contrary to popular assumption, dominant and omnipresent clubs like the Yankees and Notre Dame are among the country’s most beloved. Winning franchises usually cultivate greater fandom, just as new presidents usually see their approval ratings climb after Election Day. Americans, we are told, love and revere winners. This is a truism that Trump himself has absorbed more than anyone, which is why he’s never missed an opportunity to clothe himself in the victorious aura of coaches such as Bobby Knight, Lou Holtz, and Belichick. But even with the backing of college sports legends and an unearned reputation for ingenious dealmaking—which Democrats picked at, but could never fully dislodge—Trump still couldn’t win the most votes in November. His reputed accomplishments, and the reflected ones of other powerful men, weren’t enough to win him public loyalty.

The public’s rejection of Trump finds an echo in our treatment of the joyless men of Foxboro, Massachusetts. Sports and politics have drawn nearer to one another for some time; our best politicians use them as a tether to ordinary people, and jocks have lately become more willing to emulate socially conscious forerunners like Muhammad Ali. But football’s predominance over our other pastimes makes it an especially prominent staging ground for the social disputes of the day. These clashes, from the Colin Kaepernick patriotism scuffle to debates around labor rights and the treatment of women, are proxies for the greater culture wars being fought. Increasingly, we see ourselves in the game we obsess over.

The Patriots are the most successful entity in that game. But their success, like the president’s, brings them no adulation. There is an ambivalence about the men who prevail in our most cherished national contests. In a sense, this has always been true: Who can totally suppress his annoyance with figures who endlessly lift trophies, particularly in a time when glory and honor are so unevenly apportioned? More important, the triumphs of 2016’s greatest winners are as punishing in their monotony—their inevitability—as they are distant from our own, less triumphant lives. Everyone would like to marry a supermodel and live in unfathomable luxury, as Tom Brady and Donald Trump have done. But it’s not just that we want what these men have; it’s that the wanting seems as pointless as the winning. We have, in fact, grown tired of winners.