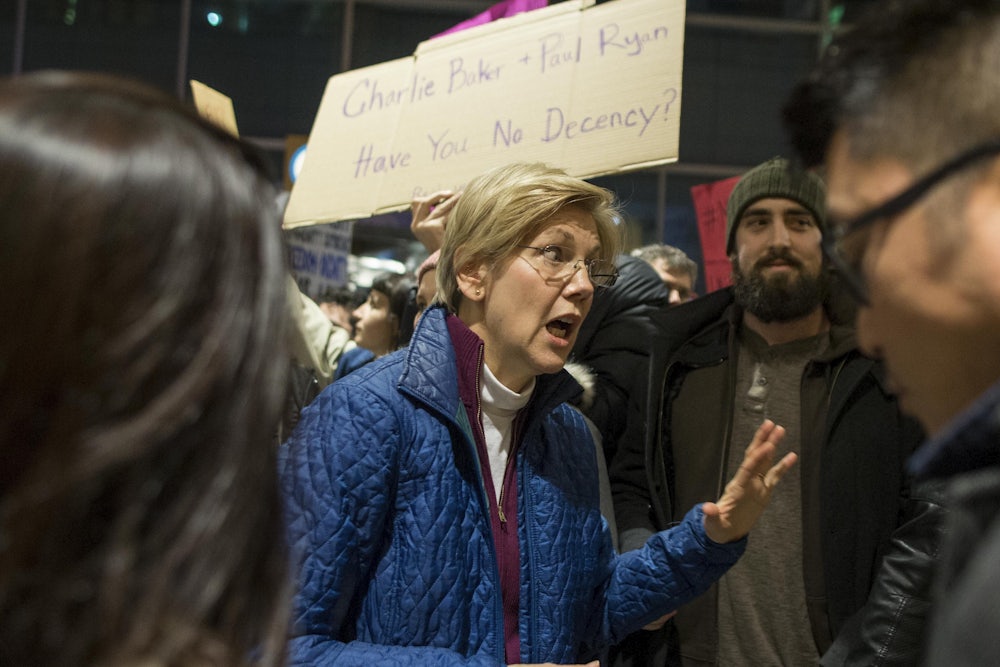

One of the most baffling things that’s happened since congressional Democrats began organizing opposition to President Donald Trump and the GOP was when Elizabeth Warren—the Massachusetts senator whom many expected to help lead the Trump resistance—decided she would support Ben Carson’s nomination to lead the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Carson is laughably unqualified for the job, and has made a second fortune for himself—as a right-wing author, speaker, and failed presidential candidate—scolding the very people who support and benefit from the programs that HUD administers. For Warren to know all this and still support Carson looked like a betrayal—something you’d expect from a Trump-country Democrat rather than one from the most liberal state in the country. That Warren is facing reelection this cycle, and an unexpectedly uncertain future, was a troubling sign for those expecting Democrats to lead an effective opposition. If a progressive champion like Warren will bend the knee, which Democrats won’t?

Here's @markos on the oceans of Democratic YES votes on Trump's nominees - including Warren's on Carson https://t.co/pDvF3OlhBt pic.twitter.com/iKyGNO5FCR

— Glenn Greenwald (@ggreenwald) January 26, 2017

Severe backlash to every perceived act of surrender can be an effective source of political pressure, as Republicans learned during the Obama years, but it can also herd the opposition party into traps. Resistance can be galvanic, but a false sense of strategic failure can be demoralizing. Quite frequently, at the urging of people who should’ve known better, conservatives scapegoated their elected representatives for allowing things to happen that those members lacked the power to stop. It was this sort of blind thirst for impossible victories that drove Republicans to shut down the government and nearly send the U.S. government into default on its debt.

There is a better balance, but it can only be struck if liberals and progressives accept that they are about to lose a whole lot of fights.

Only Elizabeth Warren knows what was really going through her mind when she gave Carson her backing, but here’s the explanation she gave—which, for whatever it’s worth, perfectly matched my assumptions about her thinking when I heard about her decision.

“A man who makes written promises [as Carson did] gives us a toehold on accountability,” she wrote. “If President Trump goes to his second choice, I don’t think we will get another HUD nominee who will even make these promises—much less follow through on them.”

At every decision point, she implies, Democrats need to ask themselves not just “can we defeat this nominee?” but also “will the next one be worse?”

The Democratic Party’s strategy for obstructing Trump’s cabinet may not be perfect, but it has generated more disappointment than it deserves. In many ways, it has been fiercer than the strategy Republicans deployed in 2009 against Obama’s nominees. The difference is that the rules since 2009 have changed, and they changed because Democrats rightly changed them. The minority party can no longer filibuster designated cabinet secretaries. That rule change in turn should have altered the metrics liberal activists use to define successful opposition. Trump will eventually have a full complement of cabinet secretaries because Republicans have the power to fill his cabinet on their own.

There are only three ways fights over cabinet secretaries can end.

1. All Democrats, with the help of three or more Republicans, deny nominees confirmation.

2. Democrats vote in lockstep (or near lockstep) against nominees who get confirmed anyhow.

3. Democrats relent.

It is tempting to assume the best strategy is maximal opposition: Make Republicans confirm all of Trump’s nominees, and maximize the odds that at least one of his nominees is ultimately rejected. But that isn’t obviously so. Carson might have been beatable on the grounds of obvious incompetence, but the subsequent nominee might have been ruthlessly competent.

The opportunity cost of universal, indiscriminate opposition isn’t just that it might be too effective—drumming out bad nominees to be replaced by worse ones—but that it collapses distinctions between the bad (John Kelly at the Department of Homeland Security) and the truly abhorrent (Jeff Sessions at Department of Justice). It is nearly impossible to imagine a worse candidate for education secretary than Betsy DeVos, who by no coincidence is one of Trump’s most embattled cabinet picks, but others are more or less the kinds of people you’d expect a generic Republican to select. Letting them through is a way to cut losses; it also helps preserve what’s left of the swiftly eroding norm that mainstream cabinet nominees should get bipartisan support to facilitate the continuity of government.

The Supreme Court is a similar story in many ways, but one where the anti-Trump left is primed to interpret defeat as capitulation. That Trump will get to fill the Supreme Court vacancy is cosmically unfair, and should taint the new justice’s perceived legitimacy for the duration of his stay on the bench. But because Senate Republicans blocked President Barack Obama’s nominee for a year, and because the minority can still filibuster Supreme Court nominees, it will be especially demoralizing when Trump’s pick, Neil Gorsuch, is confirmed in the space of a few weeks or months. The temptation will be to assume Democrats failed where Republicans succeeded.

But that comparison would be badly flawed.

If Democrats had lost the presidency but recaptured the Senate, the story would be different. But a determined majority, even a narrow one, can confirm whomever Trump nominates. It only takes 50 members to say the filibuster also no longer applies to Supreme Court nominees. Maybe Republicans aren’t so determined, in which case the opposition will have real leverage. I suspect they are, though, and when they confirm Gorsuch with a bare majority of votes this spring, the left shouldn’t dissolve into recriminations. They should accept in advance that this fight, like others to come, may be unwinnable—but that losing a fight isn’t the same as failing to rise to the occasion, and that picking only certain battles isn’t synonymous with appeasement.