In late October 2011, I was volunteering at the Occupy Wall Street library in lower Manhattan. Tucked into a corner of Zuccotti Park, the library was staffed mainly by anarchists of an exceedingly orderly bent. If society were suddenly freed from coercive institutions like libraries, these people would gladly spend the morning sorting donated books by Dewey decimal number—as they were doing in the mild fall weather. I was there for only a few days, but one conversation with a book borrower has stayed with me. He was having trouble understanding why he kept returning to the encampment. He wondered: Had anything like this happened before? Were there books that could tell him who had done it, and why? I felt I was meeting a victim of a political shipwreck. In my mind, he became emblematic of a left that felt itself so unmoored from any shared past that it was puzzled by its own existence.

Now that Donald Trump occupies the White House, it’s easy to feel that we are all castaways in historical time. There is talk in some quarters of leaving the country, of turning blue cities and states into sanctuaries, not just for the undocumented, but for disillusioned liberals—a response that amounts to giving up on creating a just and inclusive democracy in this divided land. But such feelings of despair miss the deeper and perhaps more lasting political transformation that has taken place in the five years since Zuccotti Park.

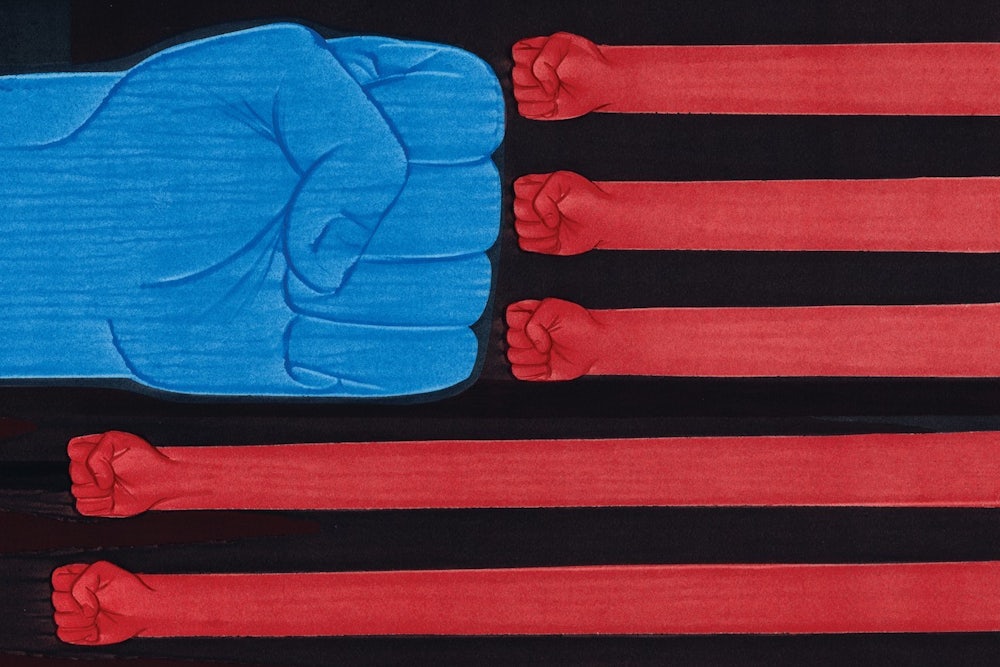

Indeed, the irruption of radicalism at Occupy turned out to be prophetic. For the first time in decades, the left regained its focus and put down new roots. Fight for $15, the campaign for a higher minimum wage led by fast-food workers, made gains in New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, and San Francisco. Rolling Jubilee, founded in 2012, bought and canceled almost $32 million in medical and student debt. Black Lives Matter has forced America to reckon with police violence against black men and highlighted the economic isolation of many black communities. Last year, Bernie Sanders won more than 13 million votes. And recent polls show that a majority of Americans under the age of 30 now prefer socialism to capitalism. While it is unclear just what they mean by that, a renewed openness to radical ideas is unmistakable among young people. The mass protests in response to Trump’s policies, both at the women’s march and at airports around the country, in the last weeks show a sense of urgency and willingness to fight for robust legal equality and inclusiveness. At the very moment when establishment politics have been severely undermined—the GOP hijacked by Trump, the Democrats confounded by Hillary Clinton’s loss—the American left has been reborn.

10 Ways to Take on Trump

John Lewis, Eliot Spitzer, Gavin Newsom, and others talk about what we can do, from Congress to the streets.

For most of the 2016 election cycle, however, the left was told, implicitly or explicitly, that while they might be charming or admirable, they should leave real politics to the adults of the Democratic National Committee and the liberal commentariat. There was one candidate, we were assured, and one web of institutions and experts who understood how to get things done: They were battle-tested and ready to win, then to hit the ground governing. The rest of us had pretty sentiments; it was sweet that we thought the word democracy could refer to something larger in ambition and imagination than the current version of the Democratic Party; but politics means putting away childish things.

In the wake of Trump’s victory in November, the present leadership of the Democratic Party has failed to grasp the lessons of its own defeat. “I don’t think people want a new direction,” Nancy Pelosi insisted on Meet the Press just after the election. The DNC doubled down on that position in early January, announcing the creation of an anti-Trump “war room” staffed with Clinton operatives who will continue attacking Trump’s ethics, character, and speculative ties to Russia. This is the same strategy that failed to win the presidential election against a palpably flawed and eminently beatable candidate.

Though fragmented and incipient, this nascent left is now best placed to mount a convincing opposition to Trump, and to engage with the forces that brought him to power. With its focus on economic inequality and collective action, the left knows things that liberals have been reluctant to acknowledge, or in any event to say—knowledge that is necessary to embrace the populist moment, push back on its reactionary inclinations, and seize its progressive potential. The left is able to diagnose the malfunctioning of our democracy because, unlike the Democratic establishment, it starts from the premise that American democracy as it is currently constituted is profoundly insufficient.

The Sanders campaign recovered eclipsed ways of talking about politics and the economy, and began reinventing them; in resisting Trump, left ideas can help to make sense of our shared experience, suggesting how life came to be as it is, and how it might be different. None of this guarantees political success, of course. But it does mean that, far from being dreamily irrelevant, the left must place itself firmly at the center of the fights ahead.

At its heart, the new populism is a revival of themes that many well-intentioned liberals thought had been stamped out long ago, at least in the world’s rich, culturally avant-garde countries: nationalism, battles over international trade, the relationship between democracy and capitalism. The liberal elites of the Clinton-Obama years believed that history itself was over, and that they were charged with supervising the eternal present that followed. Whether they had read Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, or simply absorbed a version of his ideas through liberal think tanks and Thomas Friedman’s columns, it comes to the same thing: They held that democratic capitalism, plus the defense of human rights, was the only theoretical framework left standing for making sense of human life.

This serene confidence left liberals in the United States and Europe totally unprepared for the present wave of populist insurgencies by millions of people who, whatever their other grievances, do not feel secure or dignified in their economic lives. At home, populism currently encompasses both the left-wing version of Bernie Sanders, with its calls for universal health care and a regulatory crackdown on Wall Street, and Donald Trump’s blend of atmospheric anti-elitism and a largely right-wing economic agenda. Abroad, Marine le Pen’s ethno-nationalist populism is building in France, and Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalism has swept India. We are living through a return of history.

Over the past year, two competing explanations for the populist wave have emerged. On the one hand, journalists like John Judis and Nate Cohn have traced political discontent to economic inequality and insecurity. In The Populist Explosion, Judis argues that Democrats in the United States and Europe’s social-democratic parties gave up the traditional working-class vote when they embraced free trade, failed to acknowledge class conflict, and withdrew from their traditional alliances with unions. By contrast, writing in The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that Republicans won by mobilizing voters who rejected a black president. At Vox, Dylan Matthews reviewed polling data and concluded that the concerns of Trump supporters are “heavily about race.”

It is perfectly clear that both economic inequality and racism fueled support for Trump. Only the left is equipped to explain how these two factors are entangled, by looking at the experience of life under capitalism. In this economy, most people lack important forms of security and control over their lives. They answer to bosses, who answer to investors, who answer to global flows of goods and capital. As Marx pointed out long ago, the system assigns the roles, and people fill them. An investor need not be a greedy person, nor a boss a bossy one; but if they do not maximize returns in the face of competition, they will be replaced by someone who will try harder, so they had better be prepared to act greedy, or bossy, or—in the case of the line worker—diligent and subservient.

When no one talks about how the system itself produces economic insecurity and a loss of control, scapegoating falls on the groups and individuals closest at hand. Immigrants particularly get scapegoated because often they are willing to take low-paying jobs or lack legal authorization to work. When no one in politics talks about brutal economic realities—including a merciless and de-unionized labor market, the unfettered mobility of capital, and the investor-driven imperative to squeeze every possible “efficiency” out of people—then your competitor for wages on the building site becomes the only economic rival you can actually see. Racism and xenophobia are not merely symptoms of economic anxiety, and are not to be morally or politically excused on account of hard times. But they are likely to be stronger and more politically effective when there appears to be no other way for people to address their sense of helplessness.

Liberals tend to ignore this analysis, and to personalize racism and xenophobia as moral failings, because they think the necessary preconditions for a decent cosmopolitanism are already in place: markets and multiculturalism. Conservatives from Edmund Burke to Ross Douthat have argued almost the opposite. They posit that people are basically tribal, and therefore all forms of cosmopolitanism, from liberal humanitarianism to socialist solidarity, are utopian fantasies that will reliably fall apart in the harsh light of human nature.

The left presents an alternative view: We simply don’t know what kinds of solidarity people would be capable of if they felt control and security in their lives. Historically, xenophobia and racism have been inseparable from enslavement, imperialism, economic domination or competition, and fear of losing one’s place. At the same time, people have shown enormous flexibility and resilience when they encounter changing notions of national identity (a concept that hardly existed in present form a few centuries ago), religion (witness rising secularization and syncretism), and gender identity (where our notion of “human nature” is turning out to be full of new expressions). There is no reason to assume, as conservatives tend to conclude, that what we already know marks a natural limit of human behavior or potential.

On the national stage, however, the left has not always made these ideas clear. The Sanders campaign lacked a political vocabulary for talking about the complex realities of capitalism. On the issue of trade, for example, Sanders roundly criticized liberal agreements such as NAFTA for hollowing out American industry, but he often failed to follow this deeper economic logic to its conclusion. Restricting imports would not, by itself, bring back some twentieth-century idyll in which workers shared the fruits of robust economic growth. Yes, American industries might gain a greater portion of global expenditure. But that would merely increase profits at the top—so long as investors like Mitt Romney and bosses like Donald Trump can hold automation or mass firings over the heads of recalcitrant workers.

To understand how the U.S. economy is changing, you have to understand not just trade but property law that gives workers no claim on the wealth they help to produce; labor law that makes firing easy and union organizing hard; and corporate law that helped Donald Trump stay rich while leaving indebted municipalities and investors in his wake. Turning these features of the market into political issues would help show economic life not as a naturalseeming struggle for survival, but as a legally constructed competition as arbitrary as the rules of the Hunger Games.

The left needs to get better at talking about how the economy affects the way workers view themselves and their political options—their sense of what they deserve and what is possible. The Rolling Jubilee gets at these themes by suggesting that debt is not necessarily a deep moral obligation, that there is justice in eliminating it. Calls for a universal basic income reflect the idea that people deserve some share of the world’s good things, some elementary security, just for showing up—that not everything has to be earned on the market or inherited from one’s parents. Likewise, in the Sanders campaign’s insistence on social entitlements as a right of citizenship, not a shameful badge of dependence, there was a glimpse of the older, social-democratic idea that the economy should produce not simply abstract efficiency, but security and dignified work.

The current resurgence of populism is linked to a crisis in the functioning of democracy itself. Trump won the election by scorning the political system and vandalizing its norms. But he did not create the conditions for his chaotic campaign; he merely fed on them. In much-discussed recent work, political scientists Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa found that young people across Europe and the United States are increasingly skeptical of democracy and sympathetic to strong-man rule, even military government. People may not be clear what they are rejecting when they say they don’t care about democracy, but the air of indifference and hostility is unmistakable.

In the months since the election, many have struggled to understand why voters behaved the way they did. Some centrist commentators have expressed misgivings about democracy itself, arguing that it becomes self-indulgent and destructive unless responsible elites step forward to guide political passions. Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian émigré economist, provided a memorable slogan for these worries when he wrote, in 1942, that “the typical citizen drops down to a lower level of mental performance as soon as he enters the political field.… He becomes a primitive again.” In democracies, Schumpeter continued, political judgment is “unintelligent and irresponsible,” and “may prove fatal” to any country that it governs. Writing in New York magazine after the election, Andrew Sullivan seemed to agree, arguing that support for Trump was “absolute and total . . . not like that of a democratic leader but of a cult leader fused with the idea of the nation.”

There is some truth to these arguments. We know from our everyday lives that much of our decision-making is not entirely rational. But Trump has played on a deep sense of unreality about the political process. His candidacy reflected the peculiar idea that someone “strong” and “smart” could singlehandedly master a complex world, untangle the politics of the Middle East and the South China Sea, renegotiate trade agreements, and see behind the obfuscations of intelligence agencies. This is a bizarre view of what it means to act in politics. It combines the epistemic amateurism of the conspiracy theorist with the virtual self-assertion of a first-person-shooter video game. It is an approach to politics tailored to people for whom politics is a domain of fantasy.

Who could expect political judgment to arise spontaneously in a world that does not afford many people the experience of participating in actual self-rule? Political judgment, like any other skill, is trained in practice. The decline of unions has meant fewer opportunities for workers to vote, debate, and even strike over issues that directly affect them. At the same time, the consolidation of businesses into large, integrated operations has meant that the ordinary experience of work for many people involves taking orders in a one-way and often remote hierarchy. The decline of voluntary civic and political organizations has made opportunities for democratic participation scarcer still. Although people can express themselves loudly online, or at concerts, sports events, and Trump rallies, they have few chances to practice making shared decisions with concrete consequences. The essential links between opinions and consequences are, in daily life, very weak.

This weakened sense of what it means to participate in a democracy comes at the same time as a crisis of shared truth. Rough-and-ready American success once bolstered the notion that a rich country with a “free market of ideas” should be able to sustain a good-enough democracy more or less automatically. It is increasingly clear, however, that the market for ideas works much like the market for recreational drugs: People consume the ones that relieve them of their ordinary miseries and make them feel special. Thanks to the proliferation of ideological media, citizens now enjoy the same range of choice in facts as in ideas.

Liberals and those further to the left differ sharply over how to respond to these threats to democracy. The Democratic Party professionals who circulated among the Clinton campaign and its affiliated institutions tend to accept Schumpeter’s pessimism about democratic irrationality. Instead of appealing to voters’ reason, their campaigns slice and dice voters into marketing categories. They then make targeted moral and emotional appeals to them (Trump is a bad man; be with Hillary), and use canvassing technology to prod swing-state voters who, their data models inform them, will likely support the Democrat. Clinton canvassers in Michigan, where she narrowly lost, were instructed not to engage in “persuasion,” but just to make yet another phone call or flyer drop to beleaguered folks who showed up on party lists as likely Democrats. Clinton counted on the political rationality only of an elite class of technocrats, whom she expected to bring in a victory.

By contrast, there is a swath of activists to the left of the Democratic establishment whose politics center on fostering self-rule. Labor organizers try to shore up the power of workers in workplaces from fast-food chains to universities that run on the labor of underpaid and overworked adjunct faculties. In places like Durham, North Carolina, activists from Black Lives Matter have gone beyond street protests to craft alternative municipal budgets that would redirect new expenditures on police into more inclusive and productive forms of community investment. The Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of groups within Black Lives Matter, has called for community oversight boards to supervise police departments.

These activists reject the idea that our current political crisis will be resolved by technocratic solutions or get-out-the-vote strategies alone. Over the past 50 years, low-information, low-energy democracy has limped through a period when technology and elite institutions kept disagreement within a workable range of opinion. Today, however, technology and markets will produce increasingly self-indulgent and nihilistic forms of politics, unless our response goes beyond trying to restore the familiar consensus, and pushes toward deeper forms of democratic power.

The Sanders campaign showed that it is possible to connect this sort of ground-level democracy-building with demands for a larger-scale renovation of democracy. Sanders campaigned on overturning the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United, which gives corporations the power to invest unlimited sums in political campaigns, and on moving toward a system of public financing for elections, breaking the undue influence of private wealth altogether. He also advocated easing ballot access and making Election Day a national holiday—effectively halting Republican efforts to deny the vote to minorities and other Democratic-leaning constituencies.

It would be implausible to suggest that the American left is on the cusp of any great victory. It remains far from most concrete forms of political power. Yet its intellectual clarity can help guide and coordinate the work of grassroots activists, open up new alternatives for voters, and raise the bar of public argument. Five years ago, when Occupy set up in Zuccotti Park, talk of economic inequality had long been condescended to as “class warfare.” Today, no serious argument about American politics can avoid the underlying economic reality. Pundits like David Brooks may still get away with regretting, as he recently did, that “globalism” suffers only from being “despiritualized.” In the years ahead, perhaps it will finally become impossible to talk about globalism without talking about capitalism and democracy.

Two caveats are terrifically important. First, none of this will be easy. That is in large part because the Democratic Party establishment believes in the rightness and adequacy of its ideas and is committed to maintaining its power. From the Democratic National Committee to Clinton-friendly commentators such as Paul Krugman, mainstream Democrats mocked and belittled the Sanders campaign and its supporters. Many will continue to denounce anyone to their left as naïve at best, dangerous at worst. The left must respond with ambitious but rigorous argument. We will need to challenge the establishment to address the threat of rising nationalism and the crises of inequality and democracy, while also building power that the mainstream cannot ignore.

Second, none of this criticism of liberals means jettisoning or demoting the core liberal commitments to personal freedom, especially free speech and other civil liberties. The point of the left’s criticism of liberals is that these sorts of rights are not enough to secure dignified lives or meaningful self-rule under capitalism, inherited racial inequality, and an ever-deepening surveillance state. Liberal values are not enough; but they are essential. A broader left program would work to deepen people’s lived experience of liberty, equality, and democracy—values to which liberals and the left share a commitment.

For now, the left should follow the lead of Bernie Sanders, and that of many activists who have entered state and local politics, by fielding candidates for elected office. In the two-party system of American elections, the Democratic Party is the natural vehicle for campaigns like those of anticorruption activist Zephyr Teachout, who ran for Congress in upstate New York, and Occupy veteran Jillian Johnson, who won a seat on the city council in Durham, North Carolina. The party exists to maximize political power and to support a network of consultants, think tankers, friendly journalists, and patronage seekers. The left wastes energy when it vents its indignation at the Democratic Party for being an ordinary party in these respects. By the same token, however, the left owes nothing to everyday partisanship. A political party, as Trump and the Tea Party have both demonstrated, is well worth fighting to take over; beyond that, there is nothing in it that deserves loyalty or deference.

Nor should the left take its blueprint entirely from the Sanders campaign, as extraordinary as it was. Back in October 2011, in the convivial shipwreck that was the Occupy library, it would have seemed impossible for a self-described democratic socialist to become the country’s most popular politician, as Sanders was in October 2016. In Zuccotti Park, it seemed utopian to imagine that the young activists who shut down Wall Street would wind up reviving generations of work for economic justice and democracy. Now their insights and efforts, once derided as hopelessly insufficient, serve as our starting point, however tenuous and endangered in this bizarre and chauvinistic political moment. Who can say what utopias will come over the horizon next?