It is something of an understatement, at this point, to say that no one saw Donald Trump coming. Initially opposed by almost every Republican official, Trump went over their heads to galvanize a working-class base that none of them understood existed. In the process, he exposed the party’s underbelly of bigotry and xenophobia with deliberately provocative rhetoric, and went on to make a mockery of both the mainstream media and the liberal political establishment.

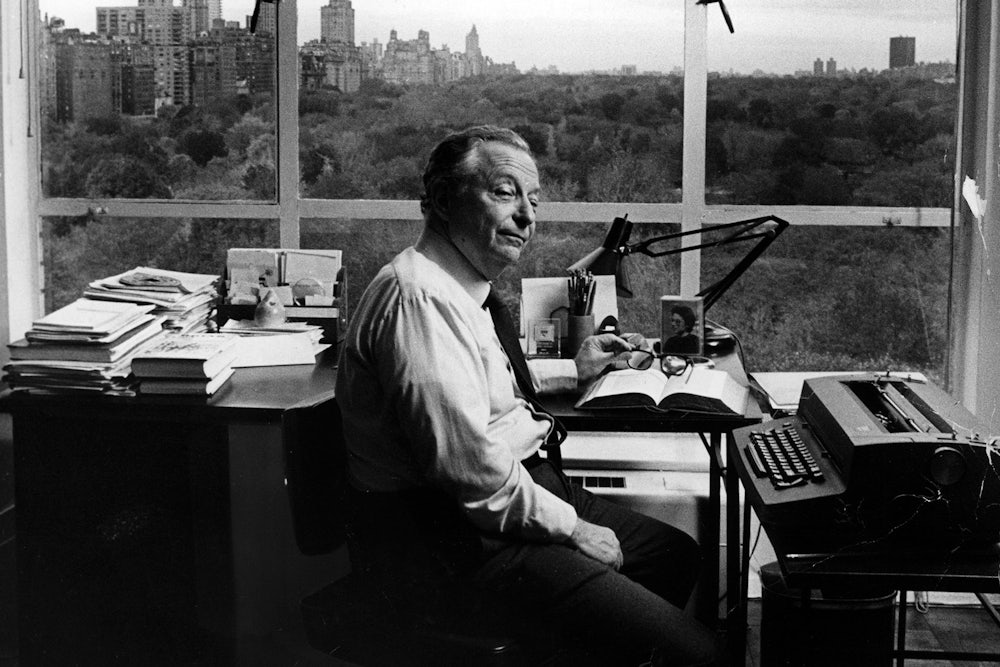

But one right-wing luminary did, in fact, see Trump coming—a full three decades before his arrival. In 1985, Irving Kristol, the leading founder of the neoconservative movement, wrote an article in The Wall Street Journal called “THE NEW POPULISM: NOT TO WORRY.” In it, Kristol foresaw the possibility that a conservative posing as a populist could one day lead a successful democratic uprising against the nation’s liberal elites. What’s more, Kristol argued, such an uprising was an absolute necessity to salvage America from what he had come to see as the pernicious effects of the Enlightenment principles on which it had been founded.

Kristol, a Trotskyite-turned-antiliberal intellectual, was at first repelled by the emerging populism of the 1970s, much of it tied to the religious right. In a 1972 article in his magazine The Public Interest, he described populism as “the belief that the world is being misdirected by a kind of mischievous conspiracy against the common man,” and noted with obvious condemnation the “tendency toward xenophobia and racism” of American populist movements of the past.

By 1985, however, after Ronald Reagan swept into office with strong support from the Christian right, Kristol had done an about-face. If there was any potential danger to republican government that concerned the Founding Fathers, he acknowledged in the Journal, it was that of populism, which he defined as “democracy at its least rational, least sensible.” The Founders knew from reading their Plato that a sudden upsurge in anti-elitist, popular passions— legitimate or not—often ended in the triumph of demagogic tyranny, a common phenomenon in the ancient world of small city states. That’s why they built into the Constitution mechanisms like the Electoral College—which Kristol hailed as a true “republican remedy for the diseases of republican government.” (How ironic that it was this supposedly fail-safe constitutional provision that put into office the first genuine demagogue in American history to accede to the presidency.)

But unlike the old kind of populism that struck terror in the hearts of the Founding Fathers, the “new populism,” as Kristol dubbed it, was nothing to worry about. In his view, the sentiments of the people now represented a “common sense” reaction against the “un-wisdom” of the elites. What was needed, he believed, was a strong leader who could rally the masses to reclaim American democracy from the clutches of liberal intellectuals, institute a faith-based government, and bind the nation together by preaching an assertive nationalism.

As political scientist Shadia Drury has pointed out, Kristol’s evolving view of populism was heavily influenced by the reactionary political philosopher Leo Strauss, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. Though atheistic in his own personal views, Strauss objected to the fact that the Enlightenment, and the philosophy of liberalism that constituted its political expression, privileged reason over religious faith, which he thought was the glue that held society together; without that glue, he believed, the social order would descend into Nazi-style barbarism. Through his reading of Strauss, Kristol was also influenced by the ideas of Carl Schmitt, who served as the legal-political philosopher of the Nazi regime in its early years. Schmitt considered the whole idea of parliamentary democracy, with its naïve and romantic notion of accommodation among political rivals, as absurd and futile. The key to politics, he believed, was adopting a “friend/foe” mentality of identifying your political enemy and then bringing about his political destruction. And the enemy, in his view, was liberalism itself, in all its manifestations.

But the most important idea Kristol took from Strauss and Schmitt may have been what Drury calls the “populist ploy”—playing on the inherent weakness of democracy itself to defeat the enemy of liberalism, just as Hitler came to power by winning the popular vote in 1932. Kristol believed that the American people were not as liberal as their ruling overlords, and that the right leader could use the democratic process to overthrow them. This new leader, in keeping with the views of Schmitt and Strauss, would then impose a national religion on America, thus unifying the country and saving it from the moral disintegration of liberalism.

Has Donald Trump successfully carried out Kristol’s “populist ploy”? To a large extent, he has. After using the democratic process to repudiate and vanquish the elite of the Republican Party, he defeated Hillary Clinton, a veritable exemplar of the liberal intellectual class despised by Kristol. Trump accomplished this feat with the strong support of conservative evangelicals, an alliance he cemented by choosing one of their own as his vice-presidential candidate, as well as alienated working-class voters in the Midwest. What’s more, he has nominated for secretary of education a woman whose life mission is to turn the American school system into a state-funded training ground for the Christian right.

Although no one in the American conservative movement went looking for a populist demagogue to pick up their banner, congressional Republicans certainly laid the groundwork for Trump’s success by wholeheartedly embracing Carl Schmitt’s “friend/foe” tactic of identifying and crushing their enemies—a strategy that also enabled them to win majorities in both houses of Congress. Intentionally or not, the GOP has effectively implemented the populist blueprint laid out by Irving Kristol and his philosophical forebears. In the final paragraph of her book Leo Strauss and the American Right, published in 1997, Shadia Drury offers a description of the neoconservative movement birthed by Strauss that doubles, virtually unaltered, as a prescient summation of Trumpism:

It echoes all the dominant features of his philosophy—the political importance of religion, the necessity of nationalism, the language of nihilism, the sense of crisis, the friend/foe mentality, the hostility toward women, the rejection of modernity, the nostalgia for the past, and the abhorrence of liberalism. And having established itself as the dominant ideology of the Republican Party, it threatens to remake America in its own image.