When I first read Dreams From My Father, I had the uncanny feeling that I myself was the subject of the book. As Barack Obama recounted the joys of his boyhood in Indonesia—running around with the children of servants, “battling swift kites with razor-sharp lines,” eating exotic delicacies like grasshopper—it was as if, in some mind-bending Borgesian sense, I was both the reader and being read. I had encountered this feeling before, in other literature, but not with such specificity, down to the “civilizing packages” of treats Obama would receive in the mail from his American grandparents. All of this was presented as if it were somehow normal. “That’s how things were,” Obama wrote, “one long adventure, the bounty of a young boy’s life.”

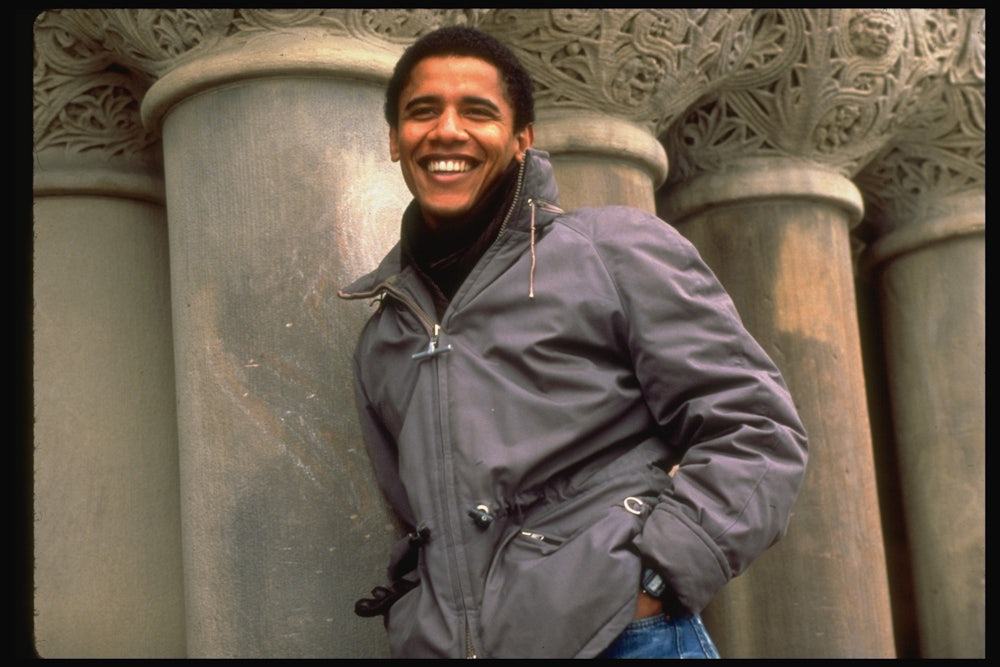

It is always hazardous to identify too strongly with a famous person. This is especially true in the case of Obama, who, despite being the preeminent figure in American life these past ten years, remains as inscrutable as any other celebrity. But I am one of the many millions of people who feel a deep connection to the man. I continue to believe that he understands me in a way that others in Washington, in Hollywood, in the New York media, in all the institutions of our cultural and political life, do not. I recognize an essential part of myself in him, and am convinced that, were he to know of my existence, the recognition would be mutual, a kind of secret we share. I realize that this may be incredibly naïve, that I may be confusing Obama with the mirror I have made of him, and yet I cling to my beliefs all the same.

Like Obama, I was born to parents of different countries and races: a Japanese mother and a white American father. Like Obama, I spent my childhood in a culture other than that of my biological parents, thanks to my father’s job as a foreign correspondent: first in Hong Kong, where I was born, then Manila and New Delhi. (The term sometimes used for such children is a “third-culture kid.”) Like Obama, I attended a high school—mine an international school in Delhi, his a prep school in Hawaii—that was akin to a multiracial utopia. And like Obama, I threw in my lot with the American aspect of my identity once I came of age, and have now lived in this country as long as I lived in Asia.

It is difficult to explain just how formative these experiences are. Foremost, there is the problem of distinguishing the peculiarities of such an upbringing from the universal nostalgia that clouds happy childhoods. If I look back on my time in Delhi in an Edenic light, and if Obama in Dreams From My Father casts the Indonesia of his boyhood in golden hues, how is that different from the eidetic memories of those who were born and raised in their own countries? There was, undeniably, the benefit of being a foreigner—of being distinct, special, superior even. There are people, particularly those sick of being another anonymous cog in the West, who become hooked on this feeling, and they crowd the bars in Bangkok and Tokyo.

But that is not what my old friends and I miss about Delhi; this is not the source of the warmth that permeates the early passages in Obama’s memoir. Jakarta in the late 1960s, Delhi in the 1990s—these were challenging places to live for a foreigner, full of inconveniences and deprivations, where poverty and misery were always just outside your door, perhaps even living alongside you in the servants’ quarters. But a place like Delhi also seemed to facilitate a more intense mode of existence. The punishing, omni-radiant heat in the summer; the herds of emaciated cows that lazed, like yogic oases of calm, smack in the middle of deadly traffic; the smog that moved in great drifts through the streets in winter; the burnt smell of desiccated dung used for cooking fuel—these only enhanced the blazes of beauty Delhi could provide, in its crumbling tombs, its lush Mughal gardens, its scorched sky flecked with paper kites. In Dreams From My Father, Obama proudly relates his habit in Indonesia of eating “small green chili peppers raw with dinner,” which to me serves as a metaphor for what it is like to be a foreigner in a developing country: There is a piquancy missing from the more insipid climes of the industrialized West.

Again, it is hard for me to separate all this from the distorting power of memory. When we are young we live very close to life, we have not yet learned the proper proportion of things, and who am I to say these experiences were more intense than anyone else’s? But I do know that they are treasured by adults who were once third-culture children, if my Facebook account is to be believed. The affection for Indonesia all but glows in Obama’s book. We carry these places with us wherever we go, and they grow mythic because we have, for the most part, left them behind for good. It is a strange and fraught concept to build an identity upon: a sense of irrevocable loss.

It is also extremely isolating. It is an identity with no outer expression, afflicting people of all skin colors, beliefs, and accents. It is almost impossible to adequately explain in casual conversation. We are akin to a minority, but one so tiny and dispersed that we have no coherent political constituency and are almost never reflected in popular entertainment. It is the kind of condition that makes one a writer, because it is all invisible, all internal, essentially confined to remembrance. The fixations it breeds will be familiar to more traditional emigrants: an almost desperate desire to belong, for one; an unhealthy obsession with the past, for another. As any melancholic emigrant will tell you, it is not only your home that you have lost, but also the person you once were.

Such a background also crosses the wires we use to identify with other people. Take, for example, our relationship to art and entertainment, the best instruments we have for understanding others and ourselves. There was never any expectation that I would encounter people like myself in movies or read about them in books. (And when I did, whether it was in the novels of Jean Rhys or in the teen comedy Mean Girls, it was with a kind of greedy hunger.) I instinctively learned to see some part of myself in all kinds of pop figures, from Rent Boy in Trainspotting to Zack de la Rocha of Rage Against the Machine. To this day, I cannot relate to statements like these, published by The New York Times, “For Asian-Americans, it’s rare to encounter a flicker of recognition in literature.” From my perspective, as a man of Asian descent, this is a sad and cramped way of looking at the world. Borges once wrote that “all men who repeat a line of Shakespeare are William Shakespeare,” and I feel the same way when I am absorbed in Faulkner or Baldwin or Woolf, even though these writers are very different from myself.

Then again, perhaps that is easy for me to say. I didn’t grow up in an environment where the racial walls were so impassable. Many of my friends were diplomats’ children, living in houses within their embassy compounds, which meant that when the big gate swung open and you passed inside, you were literally on Dutch or Thai or Canadian soil. In the early 1990s, one of my best friends lived in what was then known as the Yugoslavian embassy, which had its very own soccer field—this, more than anything else to my young mind, more than the stuffed cabbage and cigarette smoke and deep-bellied laughter, was evidence of a little globe of culture unto itself, one that was open to me through the innocent bond of friendship. And, of course, we were surrounded by an ur-culture in India that we loved and explored and took for granted, as young people do—while enjoying the foreigner’s distance from India’s own racial enmities and historical hatreds.

To relate to everyone and no one; to long for community while remaining an outsider; to build an identity from the pieces of the past; to view writing as a vessel for what would otherwise be consigned to oblivion—all of these traits I see in Obama. Ultimately, he chose to be an African-American, and this is, naturally, where we part. As Ta-Nehisi Coates noted in his recent profile of the president for The Atlantic:

Obama could have grown into a raceless cosmopolitan. Surely he would have lived in a world of problems, but problems not embodied by him.

Instead, he decided to enter this world.

To see it put this way—“raceless cosmopolitan”—is to feel, in a surprisingly painful way, the emptiness of this identity. This is the legacy of being a third-culture child, like a toll one pays for happiness. Yet the great irony of this life, one so improbable that it makes me laugh, is that of the very few public figures who share this condition—Uma Thurman, Timothy Geithner, Steve Kerr, Kobe Bryant—of the luminaries in this world who, just by existing, make me feel less alone and insubstantial, one of them is the leader of the free world. Honestly, what are the chances? It will certainly never happen again in my lifetime.

We know the dangers of reading too much of ourselves in politicians. Identity politics is a volatile force, as we have just witnessed with the election of a man who presented himself as the avenging champion of one race. But politics is not just ideas and principles and laws, but memoir, too. One of the abiding lessons of the Obama era—now widely evident in our discourse, our activist politics, and our culture—is that the experiences of those who have long been invisible matter as well. It is not mere coincidence that Obama sparked his career with a book.