Back in 2012, when Mitt Romney was the GOP’s presidential nominee, Republicans were very clear about what his victory would mean for the fate of the Affordable Care Act. That June, when the Supreme Court affirmed the law’s constitutionality, Romney’s eventual running mate Paul Ryan concluded, “We have a law that we have one more chance to repeal, and that’s this November election. That’s basically what the Supreme Court did; they raised the stakes of this election.”

Immediately after President Barack Obama won, then-House Speaker John Boehner relented momentarily to admit that Obamacare was the “law of the land,” but was quickly bullied back into rejecting its legitimacy, and Republicans spent the next four years memory-holing their pronouncements about the stakes of a second Obama term.

We are seeing now that Ryan, Boehner, and the rest were right about the importance of the 2012 election. That year, most of the Affordable Care Act remained unimplemented; today it permeates the U.S. health care system. In 2012 it had a trivial number of beneficiaries; today it has 20 million. The practical difficulties, let alone the political ones, are so daunting that Republicans would be wise to dust off that old logic—remind their voters that their last best chance to repeal Obamacare came and went four years ago—and settle now for more marginal reforms.

They are instead forging ahead, in a fit of atavism, with an attempt to repeal Obamacare anyhow. And as they essentially predicted in 2012, it is not going well. In their haste to set the law on a one-way road to extinction before inauguration day next week, they might—stress, might—close the Obama era with an ironic send-off: an implicit admission that for all intents and purposes, Obamacare is here to stay.

The flurry of activity on Capitol Hill in the past week obscures the extent to which the repeal process will be long, and will have the potential to starve itself of oxygen long before it is complete.

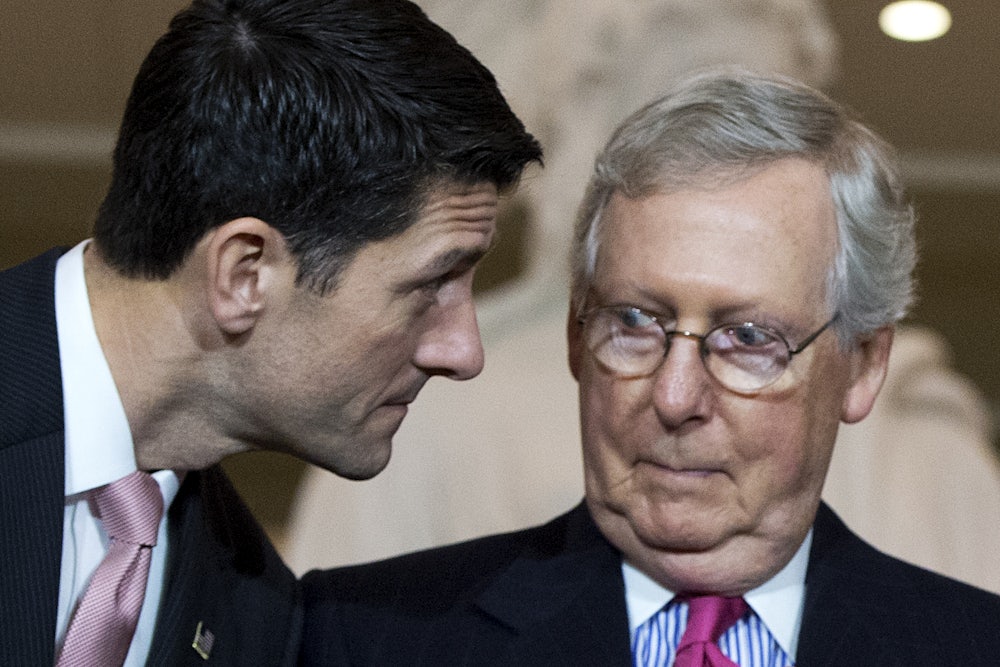

We are only at the beginning of that process; Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says his members are poised to pass what he calls an “Obamacare repeal resolution,” creating the false impression, at least in some circles, of a fait accompli—that if this week’s vote succeeds, the die is cast and Obamacare will be no more.

But that is not the case.

If the “Obamacare repeal resolution” passes this week, the effect on health policy will be precisely nothing. The resolution is more than just a declaration that the Affordable Care Act should be eliminated, but not much more. Its teeth come in the form of instructions to Senate committees of jurisdiction to write repeal legislation, and (should those committees complete their work) a guarantee that the repeal bill they write will be immune from filibuster.

But to credibly threaten repeal, first the resolution has to pass; then Republicans have to write their repeal bill; then that bill has to pass. If any of these conditions aren’t met, repeal is dead; and even if all of these conditions are met, Obamacare isn’t necessarily doomed.

The big cause for hope and determination among Obamacare supporters right now is that Republicans are all over the map, and support for McConnell’s strategy is slipping. As of Tuesday, it is safe to say they do not have the votes to repeal Obamacare; they may not even have the votes to pass the non-binding resolution that would allow them to repeal Obamacare; and they certainly don’t seem to have the will to strip 20 million people of insurance without providing them a fairly robust alternative.

There is a lot of evidence for this. In the Senate alone, multiple Republicans are tapping the brakes on the whole process. Some are demanding that the “Obamacare repeal resolution” allow committees more time to draft repeal legislation, so that it can be introduced in tandem with an Obamacare alternative.

Others (including arch-conservatives from states with large populations of ACA beneficiaries) are making the same basic argument: Whatever happens with the resolution, we can’t repeal Obamacare unless we replace it simultaneously. The chairman of the Senate health committee is on their side.

That adds up to way, way more Republicans than McConnell can afford to lose. He could conceivably bully all of them into line, and place Obamacare on a glide path to oblivion over their objections. But his margin for error is three. Three votes.

Making matters much more complicated for him is the fact that several GOP repeal-and-delay skeptics also want any replacement plan to insure as many, if not more, people than the current law does.

Far-right Republicans will have no part in that kind of moochery, of course. Ryan, the House speaker, is now bribing them with an ancillary provision to defund Planned Parenthood so that the whole repeal edifice doesn’t explode on the launchpad.

Needless to say, any “Obamacare replacement” that maintains or expands upon current coverage levels will require many Democratic votes, leaving us with Obamacare by another name, or perhaps some alternate universal coverage scheme that satisfies liberals. If Republicans manage to pass a bill that schedules Obamacare to expire in two or three years, they will be on the hook for whatever happens if they can’t broker such a compromise. Absent one, Republicans would have to choose between throwing millions of people off their insurance in 2019 or 2020 and bailing out the law with further delays.

This is all going very poorly for the GOP. There’s a reason Ryan feels the need to insist every few hours that Republicans are on a “rescue mission” to save Americans from “the damage [Obamacare’s] already done.”

If a three-year delay seems at odds with the concept of a rescue mission, you’re on to something. Navy SEALs didn’t “rescue” Captain Phillips by leaving him in limbo on the pirate boat for months and months, and Republicans aren’t “rescuing” people from anything that they’re scared to eliminate abruptly. If Ryan’s comments were an honest assessment of the Republicans’ strategy, they would not be haggling over the length of the delay.

Ryan’s language is all about willing into reality a sense (among Republicans, the media, and the wider public) that there is real urgency to acting quickly and for his members to fall into line—at least to get past step one. But the real reality is almost exactly the opposite of this. As Obama is fond of saying: in governance, reality has a way of asserting itself.