“Will François Hollande be remembered as the Franklin Roosevelt of Europe?” It was with this question that Thomas Piketty, author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century and one of France’s most vocal critics of austerity, began his reflection on Hollande’s electoral victory in 2012. There was undoubtedly a touch of irony in that question—“the comparison can make one chuckle”—but it was nonetheless an honest assessment of the forces that were already impinging on the new president and other major European leaders. In 1932, very little of what became the New Deal was spelled out in Roosevelt’s campaign against Herbert Hoover. All that Roosevelt knew was that, as Piketty writes, “the crisis of 1929 and the policies of austerity had brought the United States to its knees and that public power must reassert control over a finance capitalism on the run.” The scale of the crisis pressed Roosevelt into a daring rush of experimentation.

Piketty’s hope was that the incoming president would likewise be pressed into inventiveness and ingenuity. The crisis in Greece and the gulf between heavily indebted Southern European countries and the dynamic North would necessitate greater cooperation on fiscal policy and the mutualization of sovereign debt. Hollande, as the president of the European Union’s second pillar, would be uniquely situated to take the case for a popular redefinition of the EU to Brussels and Berlin. The rise of euro-skepticism was simultaneously a roadblock and a harbinger for dramatic change—it would create the needed opening for a departure from the norm. The rise of populism in France and across the continent would give momentum to an establishment candidate that had pledged to seriously confront inequality—Hollande became famous for the campaign promise, later aborted, to tax all annual incomes over one million euros at 75 percent.

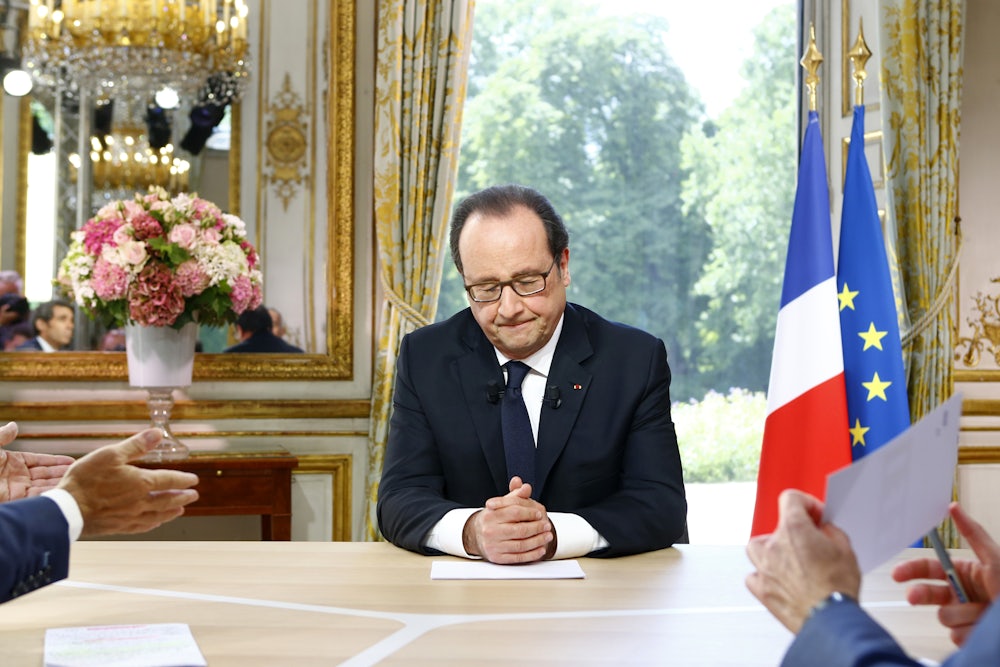

The events of the last five years have proved that Piketty’s latent cynicism was justified. On December 1, a melancholic Hollande delivered an unannounced address to the nation. At what was the lowest point in his popularity, Hollande announced somberly that he would not seek a second presidential term. The bulk of the speech, however, was largely a defense of the many controversial decisions he made after abandoning the populism of his campaign and early mandate. Large tax credits and deductions for corporate investments and the liberalization of the labor code were designed to improve the country’s business climate and ameliorate the still stagnant employment market. “The results are here,” Hollande pleaded late in the speech, “much later than I had anticipated, I admit, but they are here.” In a climate of deep insecurity, Hollande bolstered the French security apparatus, now over a year into a state of emergency. The one regret that the president admitted: proposing in the aftermath of the November 2015 Paris attacks a constitutional reform that would have enabled the nullification of citizenship for individuals convicted of terrorism.

The reform never passed. In fact, it added fuel to a growing revolt within a Socialist Party rapidly losing confidence in its own president. Hollande’s decision to step aside was born out of a frank assessment that his candidacy would do more to divide than unify a French left that had become demoralized and balkanized during his tenure. He concluded his address by hoping that his renunciation would enable “a collective spark that would encourage all progressives to unify.”

This plea has

been echoed in recent weeks by numerous calls for some form of grand primary of

progressives, which would take the place of the Socialist primary currently

scheduled for late January. Though Francois Fillon of Les Républicains

and Marine Le Pen of the National Front are the front-runners in recent polls,

the wide field of “progressives,” from centrist neoliberals to left-wing

populists, could, if unified around one candidate, form a commanding coalition.

The reality is that the growing chasm between these two poles will likely prevent

such an alliance from holding.

Donald Trump’s victory was greeted with shock and awe by the political class across Europe. In France, it could happen here was the conclusion drawn by many who had dismissed the possibility that the right-wing National Front might arrive at the presidential palace. This picture was then complicated by a new wrinkle on the French right: the surprise victory of Fillon in the conservative primary in late November, which had been previously understood as an internal battle between the liberal wing of the French right, rallied around former Prime Minister Alain Juppé, and the insurgent populism that has upended the United Kingdom and the United States, embodied by combative former President Nicolas Sarkozy.

Fillon’s victory has revealed the existence of a third force. The darling of the conservative, Catholic constituencies that hold a large sway among the French right, he is known for his staunch opposition to the expansion of gay rights. Although he has not pledged to repeal the 2013 law guaranteeing marriage equality, he has vowed to halt any further liberalization, on adoption and family rights, specifically. Among Fillon’s other controversial stances is his endorsement of calls to alter the récit national, or the national story or history, as it is taught in France’s educational system, imagined by the entire political establishment to be the bedrock of French republicanism.

Presenting a greater break from the country’s norms is Fillon’s social and economic radicalism. Imagining himself as something of a French Ronald Reagan or Margaret Thatcher, Fillon hopes to take a sledge-hammer to all that has remained to distinguish French capitalism from its trans-Channel and trans-Atlantic counterparts. For Fillon, the stagnant economy needs nothing short of unrelenting shock therapy. The “radical transformation of the country” would entail massive reductions in taxes for the wealthiest households and businesses, a drop in labor costs, and a drastic re-imagination of the French state. Speaking before a gathering of executives and tycoons on March 11, Fillon likened his first 100 days to a “blitzkrieg.”

By July 1, 2017, he looked forward to receiving a pile of reforms from the ministers of the economy, industry, and labor. These he suggested would be passed “using all the means allowed under the constitution of the Fifth Republic” including “the 49-3,” an increasingly used article of the constitution that enables the passage of a law by ministers without a vote of parliament. The Reagan Revolution by decree: One of his most infamous planks is the intention to fire 500,000 public sector workers, in a country of roughly 66 million people and an unemployment rate already hovering at 10 percent.

In other words, the social compromise that has characterized French capitalism over recent decades must be irrevocably abandoned. Even for Le Pen, Fillon represents an insufferable rupture from French norms. She has declared that she is “thrilled” by the prospect of facing off against Fillon. Despite boasting an equally frightening platform heavy on the xenophobic and nationalistic sentiment, there is a kernel of truth in Le Pen’s historical assessment of the Les Républicains candidate: “[Fillon] offers an ultra-liberalism entirely against the current of everything happening in Europe and in the world. François Fillon is like the candle salesman after the invention of electricity.”

The struggle between neoliberalism and populism is even more marked on the French left. Many have argued that the already wide field of Socialist Party candidates should whittle itself down before the primary to two representatives of these wings, so as to amplify the debate over the future of the party. Manuel Valls, Hollande’s prime minister, officially joined the race on December 5. Valls has a difficult path ahead: Though he enjoys broad support among the more conservative wing of the Socialist Party, having presided over much of Hollande’s shift from populism since 2012, he has hoped to present himself as a unifying candidate. This is ironic because Valls himself coined a now infamous phrase in French political language: that there exist two, “irreconcilable lefts.”

The self-described modern left, which Valls hopes to preserve and lead, is committed to participating in and harnessing the effects of an inherently beneficent globalization. Embracing the trajectory of the party’s development in recent decades, this wing insists on drifting away from the social compromises developed over the past century. France’s legal codes governing the ability of corporations to hire and fire workers, the argument goes, were developed at a time of stable mass industry and are buckling under the fluidity of today’s labor markets. Once occupying a dominant position in the global economy, France has grown sclerotic and must compete with a wider field of competitors. Valls argues that his faction is locked in a struggle with the forces of nostalgia. Resistance to reform is defined as clinging to the ideological struggles—capitalism versus socialism, essentially—that captivated the French left throughout the 20th century.

Hollande’s presidency gave birth to growing dissent within his own political family, where a clique has become increasingly dismayed by the trajectory of the Socialist Party. In many respects, these dissenters, referred to as the “frondeurs,” hope to restore the coalition and ideas that animated Hollande’s campaign in 2012. That the two leaders of this wing, Benoit Hamon and Arnaud Montebourg, were both former ministers of the sitting government speaks to the disillusionment with a president who had campaigned to attack income inequality and shifted to a politique de l’offre (“corporate welfare”). The desire to transform, and thereby preserve, the European Union likewise lives on among these dissenters. In a recent interview, Montebourg said that his plan is to “oppose the conservative bloc led by Germany” and to “build a reform bloc among the member countries who had placed hope in the election of François Hollande and who had been disappointed.”

This rebellion is more than a simple rejection of the policy prescriptions pursued by the Valls-Hollande duo. It is also an attack on the way government has enacted unpopular reforms. Episodes such as the passage of a package of labor reform laws through extra-parliamentary means (the “49-3”) have rightfully propagated fears about a reform-by-decree model. This reservation can hardly be characterized as a case of ideological nostalgia, as the reformers would have us believe. It is born out of a much deeper suspicion of the centrist elements of the Socialist Party: Their efforts to reform the country along more pro-business lines are perhaps only possible by curtailing the institutions of liberal democracy itself.

The calls for a broad primary of the left are directed first and foremost at the two insurgent movements that have sought to bypass the Socialist Party entirely. What we are possibly witnessing is the Socialist Party’s unseating as the center of gravity on the French left. There are now three distinct poles—a neoliberal party, an unhappy alliance of Socialists, and a growing progressive populism—that share roughly equally the remaining support of the French electorate, once you account for the right.

Taking Valls’s neoliberalism to its logical conclusion—a breakaway party entirely shorn of the ideological baggage of the Socialist Party—is the independent candidacy of Emmanuel Macron. There is very little in terms of substance that separates Macron from Valls—the conservative weekly newsmagazine Le Point, in an issue devoted to the two candidates, asked, “Is the left finally leaving the Stone Age?” What distinguishes Macron from Valls is the former’s opportunism: Macron began to abandon the Hollande ship this summer, debuted his movement En Marche! in July, resigned as economy minister in late August, and officially announced his candidacy in November.

Fillon’s victory poses some problems for the Macron/Valls project. In a campaign that had been presented as an effort to break the left-right binary entirely and establish a “progressive” versus “populist” battle, Macron now has to separate himself from a conservative candidate whose project is a more extreme version of his. (Macron was one of the staunchest advocates in the government for using article 49-3 to pass unpopular labor-market reforms.)

Although his platform remains very opaque to this day, the undeniably charismatic Macron has nonetheless crafted some interesting arguments to make this distinction. Macron’s target is not simply the old labor protections inherited from the 20th century, but the nexus of big business and government. Macron’s claim to rally French progressives is this crucial pairing. While Fillon may be the candidate of oligarchy, Macron vies to speak for the anxieties and wishes of the small entrepreneur weighed down both by an archaic labor code and tax system and monopoly. In a year in which populist revolts have shaken confidence in the economic doctrines of the past 30 years, he has innovated a brilliant strategy: re-package those old doctrines as a new form of populism.

Diametrically opposed to Macron is the insurgent campaign lead by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of the populist party La France Insoumise (“Rebellious France”). Like Macron, Mélenchon hopes to convince voters that the Socialist Party is an impossible alliance. Speaking in early December in Bordeaux, in a 100-minute address filled with historical excurses on Montesquieu, Mélenchon declared that the right’s coronation of Fillon was “a good thing” that can “clarify” the political crossroads at which the country finds itself. Fillon is “the synthesis of what the right really is in our country,” Mélenchon said, “the most absolute economic liberalism and the most total moral and intellectual conservatism.”

With such a reading of the situation it is not hard to understand Mélenchon’s refusal to cooperate with a Socialist Party led by the likes of Hollande and Valls. Mélenchon has been waiting on the sidelines of French politics for the past half-decade. What’s remarkable is that the candidate enjoys support in the mid-teens according to recent polls, which show no candidate exceeding 30 percent in the run-up to the election. All the more remarkable is that this is a figure famous for such proposals as capping the ratio of executive-worker pay at 20:1 and immediately calling a constitutional convention to usher in the Sixth Republic.

But Mélenchon is also in competition with Le Pen, whose National Front has some of its strongest support (and a few elected offices) in the old industrial heartlands of the country. This has undeniably pushed Mélenchon into flirting with a nationalist discourse himself. Mélenchon’s line comes into higher relief, however, with his declared admiration for such Latin American figures as Hugo Chavez, whom he referred to as “the infinite ideal of human hope, of revolution.” Relative to the National Front candidate, Mélenchon’s euro-skepticism is likewise tempered, if only slightly: Either the union is fundamentally re-imagined in the name of economic security and social protection (and as a political and economic counterweight to American imperialism), or France leaves.

These divisions go much deeper than the usual debates within political families. What has emerged are two distinct strategies for confronting Le Pen’s rise and, more significantly, two sharply different visions for the country and Europe. That a grand primary of progressives could paper over these cleavages would appear to be wishful thinking. What we will likely see instead is a rump primary for a rump Socialist Party ravaged by the legacy of François Hollande, the Franklin Roosevelt that wasn’t.