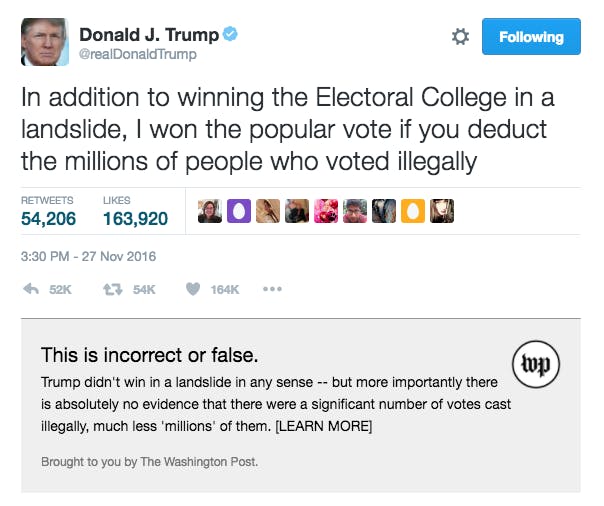

The Washington Post has created a nifty tool designed to address one of the novel problems of our political era: a president-elect who persistently uses Twitter to spread lies. A web-browser extension for Chrome and Firefox, RealDonaldContext annotates some of Trump’s tweets with fact-checking from the Post. For instance, last month Trump tweeted, “In addition to winning the Electoral College in a landslide, I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” Below that, if you use the extension, is a note saying, “This is incorrect or false,” with this explication: “Trump didn’t win in a landslide in any sense—but more importantly there is absolutely no evidence that there were a significant number of votes cast illegally, much less ‘millions’ of them.”

RealDonaldContext meets a genuine need, given the importance tweeting plays in Trump’s media strategy and the frequency with which he lies. Trump’s authoritarianism is manifest in his attempt to impose a false reality on the world, which will become all the more dangerous when he assumes power. Thus, fact-checking his tweets is not only essential journalism, but an act of resistance—a reminder that Trump can’t make a lie come true by fiat alone.

Yet fact-checking, while necessary, is also only a partial solution. Trump’s core supporters, and the Republican Party that has decided to appease them, have proven willing to swallow his lies wholesale; they are immune to fact-checkers. Moreover, the problem with Trump’s tweets isn’t just that they often contain falsehoods, but that they are deliberate provocations with the potential to cause real conflict.

Consider Trump’s tweets after China seized a U.S. underwater drone:

China steals United States Navy research drone in international waters - rips it out of water and takes it to China in unprecedented act.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 17, 2016

We should tell China that we don't want the drone they stole back.- let them keep it!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 18, 2016

The Post annotated the first tweet by noting that the act was not unprecedented: “There have been other instances in which the Chinese have seized American military property. In 2001, following a collision with a Chinese fighter, an American spy plane was forced to land in China where it and its crew were held for days.” This annotation is useful enough, but it hardly addresses the real problem: that Trump is trying, even before assuming office, to turn a minor diplomatic scuffle into a major crisis.

Trump promised during his campaign to get tough on China, and after the election he broke with nearly four decades of diplomatic precedent by taking a congratulatory phone call from the president of Taiwan. Thus, the Chinese government understandably saw Trump’s tweets about the drone as hostile in intent. “We don’t like the word steal. That’s totally inaccurate,” Hua Chunying, a spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry, said. “The Chinese navy found the device and examined it in a professional manner… It’s as if you saw something on the street and someone asked you for it, you’d have to examine if it really belongs to them.” Global Times, a Chinese state-run newspaper, took a harder line, warning that if Trump “treats China after assuming office in the same way as in his tweets, China will not exercise restraint.”

Trump’s belligerence extends beyond foreign powers. On Monday, he tweeted:

Today there were terror attacks in Turkey, Switzerland and Germany - and it is only getting worse. The civilized world must change thinking!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 19, 2016

The Post didn’t annotate this tweet, but from a diplomatic point of view, it’s just as dangerous as the China ones. Trump conflated three separate, unconnected events and—though the motive in each case had yet to be determined—he described them all as terror attacks. In doing so, he blurred the distinction that the U.S. government usually makes between terrorist attacks directed by abroad by groups like Al Qaeda and lone-wolf violence (even if it’s incited by terrorist groups). Even if Trump had been right, and it turned out all three attacks were organized by terror groups, that wouldn’t have justified his reckless assumption.

Turns out, Trump was at least partly wrong. Officials in Berlin, Germany, suspect that a truck that plowed into a Christmas market was a terror attack; ISIS has taken credit, but the driver hasn’t been apprehended. In Zurich, Switzerland, a Swiss citizen of Ghanaian descent opened fire in an Islamic center, wounding three. “We don’t believe it was a terror act,” the chief of police said. “We have no evidence of a connection to terrorism.” And in Ankara, Turkey, an off-duty Turkish cop assassinated Russian Ambassador Andrey G. Karlov and later died in a gun battle. While Trump issued a statement calling the attacker a “radical Islamic terrorist,” and the Turkish government used the incident to scapegoat a domestic political faction (the Gulenists), the killer’s motives are ambiguous; during the attack, he had shouted “God is great!” and “don’t forget Aleppo, don’t forget Syria!”

Trump will soon be president, and every tweet and other utterance will matter greatly. “The president’s words, as uttered in speeches and other official statements, literally shape American foreign policy,” Shamila N. Chaudhary, a senior fellow at New America, wrote at Politico. “In turn, State Department bureaucrats rely on the commander in chief to articulate clear, thoughtful and consistent views, based on facts and a knowledge of history. Only then can the entire weight of the large State Department bureaucracy follow seamlessly behind him—and carry out his goals.” In other words, the problem with Trump’s tweets isn’t just that they contain lies and speculation; it’s that a steady, sober foreign policy is made impossible by those tweets. If other nations take Trump’s tweets literally, as China did, there is a real possibility of military conflict.

Trump adviser Anthony Scaramucci has told the press they should not “take him literally, take him symbolically.” But if other nations follow this advice, then the value of the president’s words will be diminished. This is the sort of confusion that could easily lead to conflict, as the international community is torn between whether to believe Trump’s words or the explanation from others, whether advisors like Scaramucci or State Department officials.

Trump isn’t even president yet, and already his tweets are causing diplomatic turmoil. Fact-checking tools are helpful, but Trump’s political opposition—not just Democrats, but Republicans dismayed by his foreign policy, like senators John McCain and Lindsay Graham—they need to make the case to the American public that his tweets are a threat to U.S. foreign policy, and even to its national security. Otherwise a President Trump could start a flame war on Twitter that turns into a bloody war in real life.