In September of 2015, 14-year-old Ahmed Mohamed showed up to his high school with a clock he’d made himself. A science nerd who loved to tinker, he brought in the clock and got some praise from his engineering teacher. But later that day, when the clock beeped in English class, school officials thought it was a bomb and called police, who arrested him. It seemed clear that Ahmed, who is Muslim and whose father immigrated to the US from Sudan, was being targeted for his ethnicity or religion—hard to imagine teachers responding to a homemade electronic device with such panic if the boy who brought it in was named Tommy instead of Ahmed.

By now, that story of Ahmed and his clock is famous. In a photo that went immediately viral, Ahmed looks the consummate geek, a skinny kid in glasses and NASA t-shirt—but he is also scared and handcuffed. Scientists and science enthusiasts around the country unleashed a torrent of support. Mark Zuckerberg and a host of Silicon Valley royalty tweeted Ahmed invitations and kudos. A banner at MIT, Ahmed’s dream school, bore the #IStandWithAhmed hashtag. Ne-Yo offered to help him out if he ever wanted to get into the music business. President Obama invited him to Washington in a tweet: “Cool clock, Ahmed. Want to bring it to the White House? We should inspire more kids like you to like science. It’s what makes America great.” Ahmed and Obama met a few weeks later, at the White House astronomy night, mingling with a few hundred fellow NASA-loving students and Bill Nye the science guy.

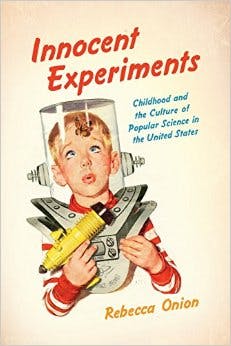

In her new book Innocent Experiments: Childhood and the popular culture of science in the United States, Rebecca Onion places Obama in a long line of American adults—from politicians and authors, to museum workers, artists and toymakers—who have celebrated youthful interest in science as a “natural” part of childhood, and simultaneously worried that too few children end up pursuing science as adults. But she also questions our ideal of the wholesome young scientist: “If we turn the twentieth-century boy chemist over and shake him a bit, questions fall out of his pockets, along with the snips and snails and puppy dog tails: Was he ever truly real? Why do we love him so much? And where is his sister?”

In the early 1900s, kids visiting the Brooklyn Children’s Museum were seen as tiny naturalists, collecting butterfly and insect specimens and later learning how to operate the museum’s wireless station, a hobby that became especially popular within the years leading up to World War I. The interwar years saw the rise of the home chemistry set, and childhood interest in science was linked not only to the national interest but to successful careers in scientifically-informed industries. Home chemistry sets even cleverly skirted parents’ concern about buying too many toys by framing the sets as a kind of career preparation, with mottos such as “Experimenter Today, Scientist Tomorrow.”

Yet, as Onion’s book reveals, not all children were equally encouraged to dive into scientific inquiry. In some cases, the exclusion of girls and children of color was incredibly overt. A 1937 chemistry set manual offers guidance for staging an alchemical magic show, with instructions for stagecraft as well as experiments. It suggests that the young alchemist choose a friend to dress up as “an Ethiopian slave,” and blacken his face and arms for the role. “If you prefer,” the manual offers, “the blackening of the face and arms can be omitted and the Assistant can be called ‘Apprentice’ instead of slave.” The faces on the covers of the chemistry sets, and in the museum materials, and in the pages of the storybooks for budding scientists are almost always white boys.

During and after World War II, a manpower crisis caused a spike in interest in women’s participation in scientific work, as women and girls were seen as “an untapped resource,” especially since they could not be drafted. Yet they were never greeted with the same enthusiasm as their male peers. When young women science students were among the winners of the Westinghouse Science Talent Search, a national program of the Westinghouse Electric Company to identify future science stars, STS publicity materials portrayed them as “nurturing and family oriented.” The boys in the program were “leaders,” the girls were photographed gazing dreamily at jewelry in a museum case. In the Science Talent Searchlight, the alumni magazine for STS winners, a cartoon showed a woman in a hospital bed holding several new babies, commenting “Thank goodness I finally have something to report to the STSL.”—even the organization that went to the trouble of educating young girls in the sciences didn’t seem to believe they’d actually become women scientists.

The adults in Onion’s book nurture children’s scientific interest because they believe that rational-thinking scientists make better citizens, or lead to lucrative careers, or align with the national interest. But these aren’t the reasons kids who love science would give you. I found myself wondering what really does make a child love science. What carries that spark from the children’s museum to the laboratory? It makes sense that the perspectives of children aren’t a larger part of the book—Onion is a historian and children don’t leave rich archives to study. But the book did leave me wondering what it is that makes some basement tinkerers and butterfly catchers go on to become chemists and biologists when others’ interest fades.

I recently had drinks with two scientists and asked if they had been into science as kids. (Not being a scientist myself, I didn’t worry about my investigation having an n value of 2, or the fact that the “sample” consisted of an engaged couple, both men working in labs in San Francisco.) What struck me about their answers was how independent their interest was from the adults around them—their love of science developed almost in spite of grown-ups intervention.

Brit, a biologist, remembered cutting into the body of an elk that had been brought into “meat shop,” a butchery class offered in his rural New Mexico grade school. Among the muscles and sinews of a leg, he discovered something strange. “A black ball,” he said, cupping his hands to indicate a globe slightly larger than a tennis ball. The meat shop teacher couldn’t tell him what it was, so Brit asked if he could keep the gruesome glob. “I wrapped it up in paper and ran across the playground to show it to the science teacher,” he recalls. The science teacher was no help either, offering a shrug and a grossed-out expression.

Like the adults that Onion cites throughout her book, Brit says it was curiosity that steered him toward a career in science. “The childhood habits of questioning,” Onion writes, were thought to be “at the heart of the feeling of science.” Brit would ask questions about the natural world that the adults around him could not answer, like “What is this thing I found in the elk leg?” and “Where does the wind go?” When I asked him if he ever found out what the black ball in the elk leg was he shrugged. “Oh, I don’t know, probably just a cyst.” He still has the feeling, but now instead of cervid cysts, his questions are directed at his research on the aging brain.

On the internet, “science” is often presented as a bunch of cool magic tricks and mind-blowing facts. Twitter accounts like “Science Porn” and “Science of Stuff” express delight in knowledge-as-meme, offering videos of cool transformations and explosions, or hallucinatory facts spelled out across a visually stunning image of cells or crystals or galaxies. It’s right to call these amusements science porn—watching a slow-mo video of black holes merging or looking at the glowing streaks of a long-exposure photo of fireflies in a dark forest is a delight for the senses. But it’s very far away from the reality of the actual practice of science.

When asked if their work wasn’t sometimes boring, my two-person sample of scientists cried out at the same time, “It’s awful!” and “So tedious.” If science requires the curious wonder of a freewheeling child, it also requires the diligent recording, repetition, and prevision of a very uptight adult. Onion quotes a blog post from science educator Marie-Claire Shanahan on the way the children-as-scientist analogy breaks down: “Child-as-natural-scientist arguments tend to equate curiosity and exploration with the expert practice of science … Science isn’t just a grown up version of a child’s curiosity. While kids have the fertile beginnings, becoming a scientist requires that they learn and skillfully practice many abstract skills that are far from intuitive.”

I took a couple of years of chemistry and biology as an undergraduate, and I remember walking out of the organic chemistry lab for the last time, feeling sad that I was never going to get to play with those cool toys again. But my scientific interest was that of a child: I had liked hooking up the tubes and watching the substances change when we did stuff to them, had liked the magic trick of cleaning the lab bench off with acetone, how the solvent made droplets of water disappear. I knew I wasn’t going to be a scientist, I didn’t have the patience to power through years of repeated experimentation. I was a science fan—I wanted to hear about the big discovery someone else had made, and to watch a cool 30-second video about it.

More than curiosity, more than patience, my scientist friends say the quality their jobs require is comfort with uncertainty. They have to sit with unanswered questions that may remain that way for years, or longer. Their research may take them in directions they’ve never considered. It’s an almost Zen state, this calmness in the face of the unresolved, and it strikes me as very grown-up indeed.

Onion shows that anxieties about the future of science have persisted throughout the century, through very different sets of circumstances. But now, one can’t help but feel, as the nation girds itself for a president who denies the reality of climate change, talks trash about the National Institute of Health and NASA, and shows a contempt for basic reason and objectivity that’s positively pre-Enlightenment, that the future of science is under threat in a way it hasn’t been for a long time. In the face of such proud and blistering ignorance, the delight that some people find in the production and dissemination of knowledge seems all the more precious and important.

At the end of the scientist’s process of tedium, bureaucracy, and uncertainty, there is often the creation of brand new knowledge. The second scientist in my very unscientific survey lit up like a Bunsen burner when talking about the moment of discovery and getting to share it—going to a conference or presenting a paper, introducing that new knowledge to the world. “It’s the biggest high of your fucking life!” he exclaimed, practically leaping off the ground with glee. That electrified feeling—more than any chemistry set or whimsical museum installation—is the message for the kids.