Since Rodrigo Duterte was elected president of the Philippines last June, he has waged a brutal crackdown on drug dealers and addicts. Nearly 4,000 people have been killed by government forces, and Duterte has invoked the Holocaust to describe the scope of his ambition. “Hitler massacred three million Jews,” he declared in September. “Now there is three million drug addicts. There are. I’d be happy to slaughter them.”

Duterte’s authoritarian rhetoric has elicited sharp condemnations from human rights advocates and foreign leaders. But there’s another front in his war on drugs that has escaped international attention. Last fall, as I reported on the violence in the Philippines, I picked up an ardent critic on social media. Her name was Madelyn, and she was young and attractive, with long hair and deep, brown eyes. When I posted about Duterte’s war on drugs, Madelyn responded with derision. “Maybe u are anti-Duterte TROLL,” she tweeted. “A foreigner who knows NOTHING bout my country.” She seemed to devote her waking hours to spreading her love of Duterte and assailing anyone who questioned him, posting dozens of times a day. “My President and I am proud of him,” one tweet read. “Get lost critics!”

Madelyn, it appears, is part of a vast and effective “keyboard army” that Duterte and his backers have mobilized to silence dissenters and create the illusion that he enjoys widespread public support. Each day, hundreds of thousands of supporters—both paid and unpaid—take to social media to proselytize Duterte’s deadly gospel. They rotate through topics like corruption, drug abuse, and U.S. interference, and post links to hastily cobbled-together, hyper-partisan web sites at all hours of the day and night. Though social media is designed to make each user appear to be a unique individual whose views are her own, Madelyn and her cohort stick exclusively to the Duterte talking points, without any of the cat GIFs, funny asides, jokes with friends, or other elements that populate most people’s feeds.

When Facebook and Twitter were founded a decade ago, they heralded a new era in which the voices of ordinary citizens could be heard alongside—or even above—those of establishment insiders. From the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter and recent demonstrations against Vladimir Putin, activists have used social media to attract followers and broadcast their messages free from official oversight. But increasingly, authoritarian regimes like Duterte’s are deploying social media to disseminate official propaganda, crack down on dissent, and maintain their grip on power. What began as a tool of freedom and democracy is being turned into a weapon of repression.

“For authoritarian states, social media censorship will increasingly be seen as an essential aspect of the security apparatus,” says Eric Jensen, a sociologist at the University of Warwick in Coventry, England, who specializes in online public engagement. “There has been a pattern of civil society embracing opportunities for more open communication, such as social media—followed inexorably by a gradual colonization of those communication channels by corporations and government.”

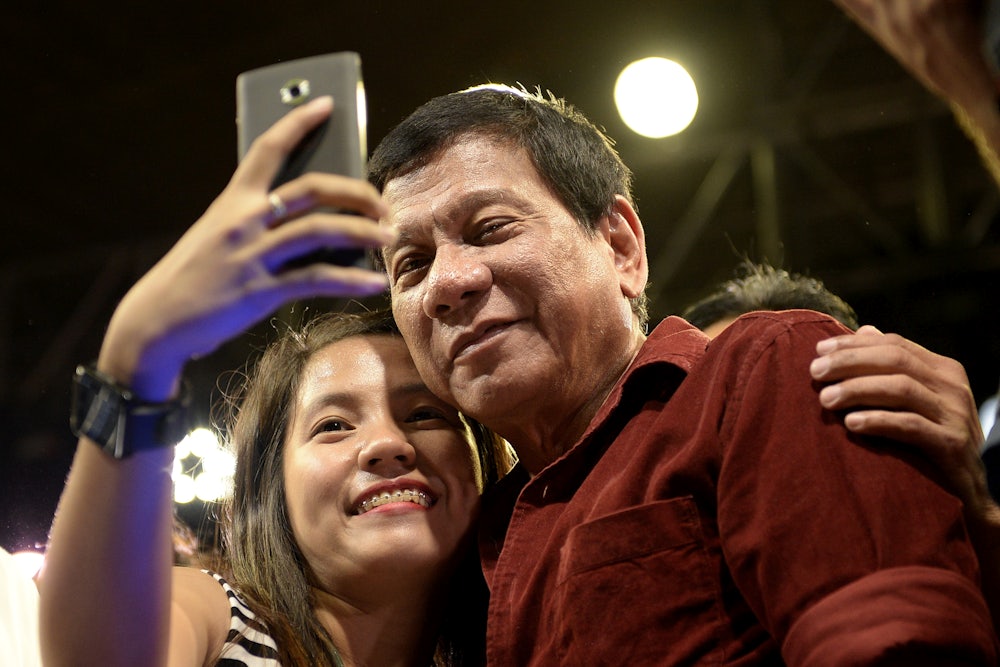

Duterte’s social media campaign began while he was the mayor of Davao, where he allegedly ran death squads to curb rampant drug dealing and other street crime. In November 2015, when he decided to run for president, he enlisted a marketing consultant named Nic Gabunada to assemble a social media army with a budget of just over $200,000. Gabunada used the money to pay hundreds of prominent online voices to flood social media with pro-Duterte comments, popularize hashtags, and attack critics. Despite being vastly outspent by his rivals, Duterte swept to power with almost 40 percent of the vote. After the upset victory, the new president’s spokesman issued a warm thanks to Duterte’s 14 million social media “volunteers.”

The Philippines seem tailor-made for this kind of propaganda machine. The median age in the country is only 23 years old, and almost half of its 103 million citizens are active social media users. Access to Facebook is provided free with all smartphones, but Filipinos incur data charges when visiting other web sites, including those of newspapers. As a result, millions of citizens rely on social media for virtually all of their news and information, consuming a daily diet of partisan opinion that masquerades as fact.

Duterte has taken advantage of this media landscape. Online trolls can earn up to $2,000 a month creating fake accounts on social media, and then using those “bots” to flood the digital airwaves with pro-Duterte propaganda. According to Affinio, a social media analytics firm, a staggering 20 percent of all Twitter accounts that mention Duterte are actually bots. Thanks in part to this constant thrum of pro-Duterte messaging, the president has maintained an approval rating of more than 80 percent.

As my encounters with Madelyn illustrate, Duterte’s supporters are also quick to attack the president’s critics. Leila de Lima, the country’s former justice secretary, has endured death threats and online abuse since she launched an inquiry into Duterte’s current policy of extrajudicial killings and alleged use of death squads in Davao. Ellecer Carlos, a human rights advocate, was forced to change his Facebook profile after he received repeated threats of violence. In a country where antigovernment activists have been killed during Duterte’s drug war, Carlos takes such threats seriously. “Sometimes you go home, you’re alone, and you need to buy something from the store,” he says. “Then the fear kicks in.”

Such tactics are being employed by authoritarian regimes around the world. China’s Communist Party has mobilized a network of government bureaucrats known as the “50 cent” army to post 450 million fake comments a year on social media. In Russia, the Kremlin finances a huge army of trolls who post disinformation all over the web. In Egypt, where Twitter and Facebook helped topple Hosni Mubarak’s regime, the military-led government has tracked, silenced, and in some cases killed its opponents. In many countries, governments routinely spy on social media accounts, assisted by a raft of private firms. Procera Networks, a Silicon Valley startup, has signed a contract with the Turkish government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to extract usernames and passwords from unencrypted web sites. The Turkish government could use that information to spy on political opponents. “People could well die from this work,” one former Procera employee told Forbes.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Back in 2012, as Facebook prepared for its IPO, Mark Zuckerberg wrote a letter to investors touting the company’s role in helping ordinary citizens hold their leaders accountable. “By giving people the power to share, we are starting to see people make their voices heard on a different scale from what has historically been possible,” he wrote. “These voices will increase in number and volume. They cannot be ignored. Over time, we expect governments will become more responsive to issues and concerns raised directly by all their people.”

Unfortunately, Zuckerberg was only half right. Social media has undeniably helped activist movements draw attention to their causes. But regimes around the world have figured out how to use social media to build even bigger megaphones, effectively drowning out dissent. In the Philippines, the massive online army has chilled public opposition to the crackdown on drug users. In one Manila slum I visited, where English terms like “human rights” and “extrajudicial killings” are sprinkled into Tagalog like grim shibboleths, almost everyone opposes the bloodletting. Some criticize the drug lords; others save their ire for overzealous cops. But no one blames the president. When I mention Duterte’s orders to shoot drug addicts, one mother simply shrugs her shoulders. “I don’t read the newspaper,” she says. She gets her news exclusively from Facebook.