Fifty-odd years ago, the Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg wrote an essay about marriage called “He and I.” Thirty years after that, the American journalist Lynn Darling wrote one called “For Better and Worse.” The titles alone make these pieces sound as though they might belong in a “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” column—but they don’t. Both grew out of raw, unmediated experience, and both are saturated in a visceral reality that reaches beyond marital complaint into the territory of existential testimony.

The American announces straight off, “When I was single, I equated marriage with drowning: Your identity disappeared, your privacy was invaded, your self submerged. After I married, I found out that I was right; what I hadn’t known was how much of an amphibian I could be.” She adds to this a long recital of the surprises (pleasant and otherwise) that the coming years were to hold, including the one that delivered an angry shock during their first year together.

When Darling’s husband bought her red bathroom towels for Valentine’s Day, she cried because she thought the honeymoon was over. “We were not really married then,” she observes ruefully, “we were still in teen-romance mode—he loves me, he loves me not—still riveted by the high drama and pitched emotion of courtship and passion.” Years later, she and her husband laugh together over the incident, “But the laughter is its own edgy commentary on how things have changed . . . how the two people who smile at this joke are indelibly stained with each other’s expectations and disappointments, how who we are is a composite of who we might have been refracted through the lens of whom we married.”

As for the notoriously unsentimental Natalia Ginzburg, she begins with an astonishing laundry list of the differences—some vital, some trivial—between her and her husband: “He always feels hot, I always feel cold. . . . He loves the theater, painting, music, especially music. I do not understand music at all, painting doesn’t mean much to me, and I get bored at the theater.” Soon the list becomes so stark the reader cannot help wondering how on earth they ever managed to live together.

Then, at the very last, Ginzburg pulls the whole piece together with an evocation of how once upon a time, very long ago, these two, almost strangers to one another, took an evening walk together and, while each found the other attractive, they were equally “ready to say goodbye to one another forever, as the sun set, at the corner of the street.” Only they didn’t, and here, more than two decades later, they were. Over the years, Ginzburg has often marveled at the fact that “he and I” fell randomly together when it was just as possible to have fallen randomly apart. It is the very randomness of their destiny that has held her attention over time; the randomness of life itself that got cemented into a relationship that somehow became a marriage.

In each essay, the writer seems, as she writes, to be discovering the mysterious in the familiar. The more she contemplates the everydayness of her life, the more amazed she becomes. Stunned, in fact. Stunned by what it actually means: being married. When people live together without the benefit of the legal tie, there is often talk of the anxiety of not being fully committed; but when they are legally bound, and have now become “husband” and “wife,” the psychological power attached to no longer beginning and ending with oneself in the eyes of civil society is felt 24-7.

In both the Ginzburg and the Darling essay, the shock of the quotidian is central to the internal action of the piece. It’s extraordinary, the writing seems to say, this compelling need to rationalize the trade-offs, endure the intermingling of contradictory emotions—admiration, dislike, desire, distrust, stimulation and boredom, exile and ease—none of which will ever separate out; and all because of the blind hunger to mate that, without exception, characterizes animal life.

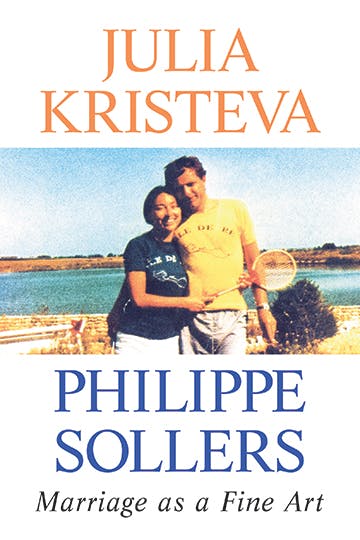

Marriage as a Fine Art is a book of conversations between the celebrated French power couple Julia Kristeva and Philippe Sollers, in which they open themselves to a barrage of questions about their own marriage. This subject matched with these participants must seem highly suspect to many: Kristeva is a world-famous psychoanalyst and feminist theorist and Philippe Sollers a novelist, critic, and magazine editor well known in France. The couple has been married for 50 years, and has for just as long been part of an elite circle of intellectual theorists—including such figures as Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Lacan—where defending marriage as such is the last thing on anyone’s agenda. So what were these two now up to?

In her preface to the book, Kristeva promises “to tell all about a given passion, with precision, without shame or shirking, without altering the past or embellishing the present, and steering very clear of the flaunting of sentimental fixations and erotic fantasies so prevalent in the current ‘selfie’ memoir.” Sollers adds that when “people get married out of calculation or delusion, time wears down this fragile normality contract, they get unmarried, they remarry, or else they stagnate in mutual disappointment. Nothing of the sort with us: Both partners equally preserve their creative personality, each stimulating the other all the time.” It’s a “new art of love,” he proposes, one that he believes society may not, however, be ready to accept. Thus, from the very start, both respondents took pains to establish their attachment as an example of the intelligence and courage that it takes to rescue the words “husband” and “wife” from their ever-increasing lack of prestige.

Kristeva and Sollers met in Paris in 1966 when she was 25 years old and had just arrived on a fellowship from Bulgaria, and he was 30, already a published writer, and a disaffected son of the French middle class. No sooner had they begun talking than each recognized in the other an exciting kindred spirit. Two years later they were married and, from that day on, the conversation between them has not ceased to flow. This intellectual companionateness, both aver, has established the kind of equality that is vital to a successful marriage. It also doesn’t hurt that Kristeva and Sollers are equals insofar as material independence goes. Sollers, sounding for all the world like an American feminist as well as a French bourgeois, confides that without equal earning power, “there’s not much use in talking about the sophistication of love or the ins and outs of fidelity.”

Kristeva laughs and assures the reader that Philippe is only speaking the simple truth. The problem is both Kristeva and Sollers are incorrigible intellectuals, constitutionally incapable of a simple anything, much less a straightforward answer to a straightforward question. For each, theory is mother’s milk, abstraction the staff of life. To be sure, bits of concrete information—including the fact, mentioned on the book jacket, that Kristeva and Sollers do not actually live together—appear alongside abstract disquisitions on literature, social history, analysis, you name it. But while their book is characterized by intellectual elegance, not much of what they say has the feel of flesh-and-blood reality.

Kristeva, especially, sins on this score. When asked how she herself would respond to a clear instance of infidelity, Kristeva observes, “In male-female relations, you can engage in ‘outside’ friendships that are sexual and sensual while still respecting the body and sensitivities of your main partner”—and adds that she herself has never known jealousy and thus could never feel betrayed. “To feel betrayed,” she clarifies, “implies zero self-confidence, a narcissism so battered that the slightest affirmation of the other person’s individuality is felt as a crippling blow.” Huh?

Thinking back to the Darling and Ginzburg essays, I could not help admiring anew the fearlessness with which those writers evoked the pleasures and pains of that extraordinary contractual relationship into which two human beings, no matter how many times they’ve performed the ceremony, enter as innocents and emerge initiates. In contrast, Kristeva and Sollers’s presentation of their marriage seemed the work of two people who think openness equates with exposure, and thus were more involved with self-protection than with truth-speaking.

Towards the end of one conversation, however, they each answer a question that breaks their uniform imperturbability and, inadvertently, delivers a flash of emotional rupture. When the hapless interviewer insists that whether to confess or to deny an infidelity is still the great question in marriage, Kristeva instantly announces, “I don’t believe there can be secrecy.” But Sollers declares, “I don’t believe in transparency . . . I’m all for secrets.” Secrets, he persists, are the real foundation of liberty. I could not help recalling that the couple does not live together, and began mischievously to wonder exactly how open this marriage is; and at what emotional cost; and if the cost is being paid equally.

It is my fervent belief that no reader could come away from this book with anything like a usable insight into the actualities of the Kristeva-Sollers marriage—or, for that matter, into the institution of marriage itself. At the same time, I’d also bet that nearly everyone will come away exhilarated. The performance, so smart, so practiced, is genuinely entertaining, enacted, as it is, by two people who are openly energized by showing off to and for one another. Their mutual enjoyment, as they go through their paces, is palpable. Clearly, intellectual busking is the glue that binds Kristeva and Sollers to one another.