Austyn Crites, a 33-year-old Republican disgusted by what he sees as the Republican nominee’s “fascism,” went to a Donald Trump rally Saturday in Reno, Nevada, with plans to launch a silent protest. It was anything but silent. when Crites got close to the stage and held up a sign reading “Republicans against Trump,” rally-goers tackled him to the ground and allegedly kicked, punched, and choked him. Then someone shouted “gun,” and the Secret Service rushed Trump off the stage while police handcuffed Crites.

There was no gun; police released Crites after a brief interview. But a myth was born: Trump had survived an assassination attempt. In a subsequent rally in Denver, Trump was introduced by Father Andre Y-Sebastian Mahanna, a Maronite Catholic priest who lamented the “attempt of murder against Mr Trump.” The false narrative quickly became Trumpian lore on social media and was echoed by prominent members of the campaign, including Donald Trump, Jr., and social media aide Daniel Scavino.

Crites’s ordeal was real. He feared for his life. “There were people wrenching on my neck they could have strangled me to death,” he told The Guardian. But Crites story is also a perfect symbol for the larger problems faced by his brand of opposition politics. Over the last year, one of the most intriguing developments in American politics has been the emergence of a faction of Republicans who find Donald Trump intolerable: #NeverTrump, to use its social media moniker. Like Crites’s protest, NeverTrump has been noble in intent (putting national interest above party loyalty) but ineffective and even counterproductive in result. Not only has it failed to convince most Republicans; it might even have helped Trump by giving him a convenient scapegoat to blame for the problems of his candidacy. If #NeverTrump is ever going to be an effective force in reforming the Republican Party, they’re going to have to figure out what they did wrong.

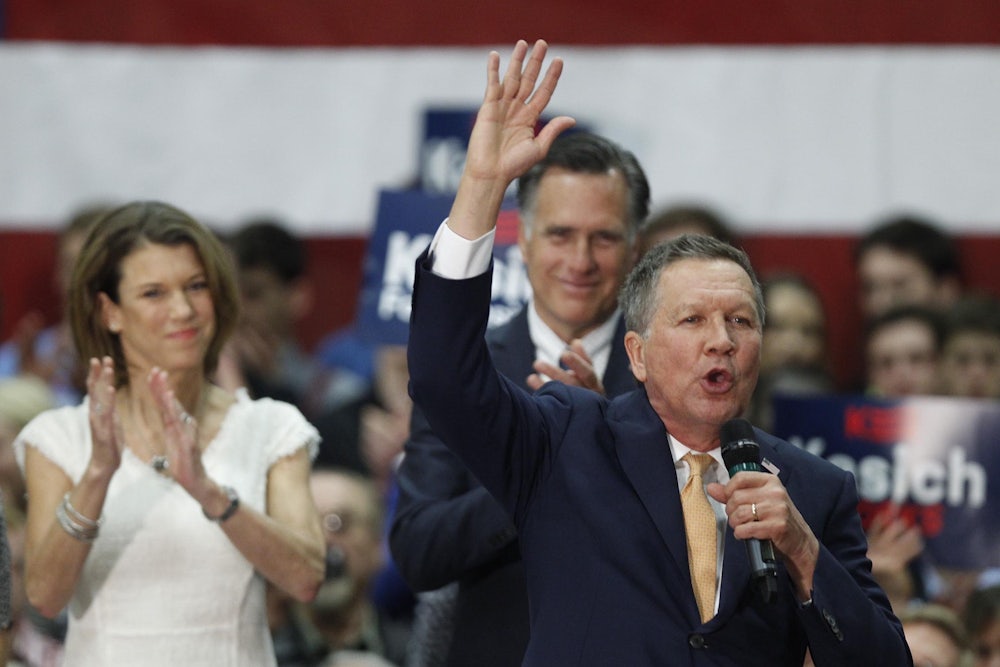

Trump has been criticized by Republicans from the moment he announced his candidacy on June 16, 2015, but it’s fair to say that for many months he was wrongly dismissed as a passing fad, in the manner of Herman Cain and Newt Gingrich in 2012. The panic that led to NeverTrump really began in late February 2016, after Trump’s victories in New Hampshire and South Carolina, when party elders like Mitt Romney and Karl Rove started organizing in earnest to stop him. But it was already too late by then, as Trump enjoyed a beachhead of support that he carried to victory in the primaries.

NeverTrump was always more of a tendency than a coherent movement, and it suffered from the same factional divisions that allowed Trump to dominate over his Republican rivals. The NeverTrump camp could never agree on who they wanted to stand as an alternative to Trump—Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz, or Marco Rubio? Muddying the waters, conservative pundits like William Kristol started entertaining fantasies of some mysterious new champion emerging, a daydream that sometimes took the form of Mitt Romney but then devolved into ever more obscure figures, like National Review writer David French, until finally settling on the quixotic campaign of former CIA operative Evan McMullin.

The search for ever more esoteric alternatives to Trump points to another failure in NeverTrump: They misjudged everything about the Republican Party, from the nature of the electorate to the moral fortitude of party leaders to the power of partisanship.

NeverTrump thought the Republican base wanted a conservative ideology rooted in the Constitution and free market thinkers like F.A. Hayek, when a plurality of that base really wanted racist appeals to white grievances; Trump has made all too clear that when it comes to limited government, the GOP base mainly wants to restrict policies that help non-whites.

NeverTrump also thought figures like Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz would take principled stands against Trump. On February 26, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat tweeted:

Time for a prediction: If Trump is the nominee, neither Rubio nor Cruz will endorse him.

— Ross Douthat (@DouthatNYT) February 27, 2016

In fact, those politicians, who have a better sense of where the party’s grassroots are, caved and supported Trump (in Cruz’s case after putting on a ridiculous drama about his tortured conscience).

Finally, NeverTrump thought there was enough opposition to Trump that they could rally followers to support third-party candidates like McMullin or to stay at home, thus making a real difference in the election. This was the biggest illusion of all. If Trump loses, it won’t be because of garment-rending manifestos like the National Review’s “Against Trump” special issue, but because Clinton rallied the Democratic base (people of color, millennials, single women, college educated whites) in sufficient numbers.

The GOP—not just Trump’s hardcore supporters, but the party base as a whole—has learned to live with their nominee. Citing the latest tracking poll, The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake noted on Friday that “the Republican base is as united in voting for him (87 percent of them are behind him) as Democrats are in voting for Hillary Clinton (also 87 percent).... In other words: It looks like the NeverTrumpers are leading a movement without a real base. And no matter what happens on Tuesday, they’ll have a mess to clean up.”

If Trump wins, NeverTrump will be enemies of the new Republican president. If he loses, they’ll be among the fall guys blamed for the loss. Interviewed by MSNBC last month, Trump campaign manager Kellyanne Conway lamented, “We have the Never Trumpers who are costing us 4 or 5 percent in places.” (As the race has tightened, the Trump campaign has downplayed the dangers of NeverTrump in favor of claims of a “rigged” election.)

It’s easy to imagine NeverTrump going into a long-term exile from politics: at home with neither the post-Trump Republican Party nor the increasingly progressive Democratic Party. Perhaps in seeking consolation for their repeated failures, the NeverTrump faction will take consolation in their own alternative fable, a Lost Cause narrative whereby they are the true heirs of Reaganism, usurped from their rightful place by the orange Pretender.

For the good of both the GOP and America, NeverTrumpers must not indulge in such nostalgic fantasies. The Trumpified Republican Party is a nightmare, and there is no one more likely to repair it than NeverTrumpers. But if they want to do the job, they have to give up the pernicious habits that allowed them to lose to Trump. The earlier #NeverTrump complaints that “Trump is a liberal” have been disproven by Trump’s success in mimicking, albeit often in crude terms, standard conservative rhetoric about filling Supreme Court vacancies, a muscular foreign policy, and the general horridness of the Clintons. They have to stop pretending that all the party needs is a return to Reaganite bromides about low taxes, American exceptionalism, and family values, since Trump has shown how easily such slogans can be co-opted by a cynical outsider.

NeverTrump’s best hope for returning their party to a rational and functioning organ in national politics is to recast Trump’s powerful nationalist appeal, but in a less toxic form. The core of Trump’s politics are immigration restriction, protectionism, and a unilateralist foreign policy. It might be possible to offer a less abrasive version of these policies: immigration restriction without the xenophobic bashing of immigrants, opposing trade agreements that offshore American jobs, and a realist foreign policy that eschews the adventurism advocated by neoconservatives. This Trump-lite policy cocktail could be combined with a more vigorous policing—by Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell on down—of conspiracy-minded conservative media such as Breitbart and Alex Jones.

A reform agenda along this line may or may not work, but it would engage with the actual politics of the Republican Party in a more realistic, constructive way. And it’s not as if the NeverTrump movement has anything left to lose.