There isn’t a word in English to describe the special kind of sadness that descends when a visitor leaves. It’s both a sense of relief (you get your space back!) but also an awareness that your guest has left an emptiness behind. In the language of the Baining people, a tribe in Papua New Guinea, the emotion is called awumbuk. The Baining think that visitors, in order to “travel light,” leave a layer of themselves behind, which hangs like a heavy mist over their hosts. The only way to dispel the mist, which can linger for days, is to set out a bowl of water overnight. The water will absorb the sad air and can be tossed out the next morning.

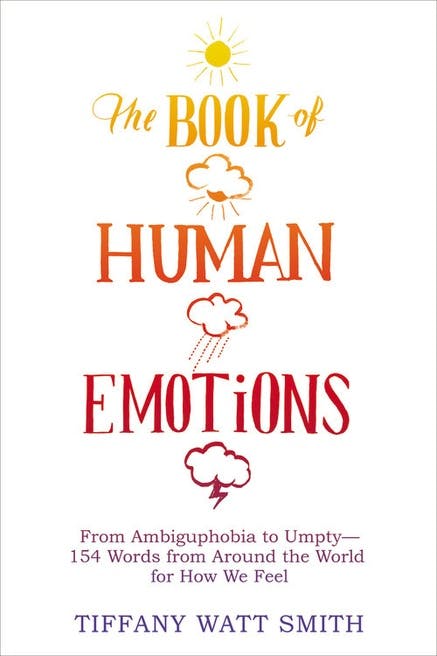

In The Book of Human Emotions, a collection of alphabetically-arranged mini-essays, Tiffany Watt Smith, a cultural historian at the Centre for the History of Emotions in London, has collected words like this from all over the world. It’s largely a playful and lighthearted book, but Smith’s underlying goal is radical: “If our emotions are so important to us today, if they are measured by governments, subject to increasing pharmaceutical intervention by doctors, taught in our schools and monitored by our employers, then we had better understand where the assumptions we have about them come from.” Smith thinks that examining the language of emotions holds the key to understanding emotion itself, leaving us better able to resist the attempts of governments and companies to manipulate us. These concerns couldn’t be more well-timed, and it’s all because of a word that isn’t in Smith’s book, but which inspires in nearly everyone the strongest of emotions—fear, pain, anger, hope, disbelief, and disgust—and which may be the single most emotional word of this year: Trump.

Trump has brought emotion to the election more than perhaps any previous candidate, even including Obama, the candidate of hope. There is the startling euphoria among supporters at his rallies, and the unique feeling of terror and depression he sparks in liberals (and even many conservatives). Yet the reason that Trump should be considered as fundamentally an emotional phenomenon is not because of the different reactions that he inspires but because he doesn’t distinguish between different emotions at all. Trump doesn’t recognize the differences between his subjective feelings (“Nobody has more respect for women” than he does, he claims) and objective facts (he has a trail of accusations and allegations of sexual assault and discrimination). It turns out you can build a whole presidential campaign on blurred emotions.

It wasn’t until the early nineteenth century that the concept of—and word for—“emotion” came into use. Before then, we spoke of love, hate, or jealousy, for instance, as types of “passions” or “appetites” or “humors.” Each of these words implied forces that act upon us—arising from either the supernatural world or from our own bodies. In 1820, the Scottish philosopher Thomas Brown suggested that a new, more precise language was needed for the category of experiences and mental states. In lectures Brown gave in Edinburgh, he repurposed a French word, émotion, which had previously been used to describe the movement of physical bodies. Emotional states could be seen—for instance, in wide eyes and trembling hands, reflexes that showed how the brain was processing stimuli.

Charles Darwin, early in his career, also began to study how emotions were expressed. “The language of the emotions, as it has sometimes been called, is certainly of importance for the welfare of mankind,” he later wrote in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). In order to understand that language, Darwin sent questionnaires to missionaries and explorers, asking them how the people they met expressed fear and excitement. He conjectured that emotions are not “fixed responses, but the result of millions of years of evolutionary processes that were still ongoing…our emotions were there because they had helped us survive.” Emotions, in short, were nothing less than inherited reflexes.

At the end of the century, Freud began developing a theory of emotions that ran directly counter to Darwin’s purely biological one and explained them as arising, as Smith summarizes, from the “elusive and complex influence of the mind, or psyche.” Seeing emotions as not just evolved responses gave them new dimensions: Now they could be repressed, parasitic, hidden, forgotten, and transformed. Darwin and Freud, Smith points out, “are responsible for two of the most influential ideas about our feelings today: that our emotions are evolved physical responses, and that they are affected by the play of our unconscious minds.”

Perhaps the most influential modern thinking about emotion is the so-called universal emotions theory, a loose set of ideas developed across decades by various anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists. In the 1960s and 70s, the psychologists Paul Ekman and Carroll Izard argued for the existence of a small group of basic emotions—happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise—that all humans both experience and express in the same way, regardless of cultural or historical context. Smith’s book offers a subtle corrective to such essentialism, and she is less interested in root causes than in sheer diversity, hunting worldwide for rare and far-flung emotions, like some Victorian botanist on the hunt for new species.

To interpret her finds, she draws on what the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz in the 1970s called “thick description,”—that is, description that engages with minute historical and cultural context. “Without context,” Smith says, “you only get a “thin description” of what is going on, not the whole story—and it’s this whole story that is what an emotion is.” Han, for instance, is the Korean word for “a collective acceptance of suffering combined with a quiet yearning for things to be different.” While understandable in English, han achieves more complex resonance when considered alongside Korea’s many periods of occupation by foreign powers, from the Mongols in the thirteenth century to the Japanese in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

When you look at Trump’s campaign through the lens of Smith’s book the thing that jumps out at you is that the candidate invariably opts for thin descriptions of emotion. Take “disgusting,” one of his favorite words. A lot of things disgust Trump, especially women: they “bleed out of their wherever,” they breastfeed their newborns, they gain weight and have sex, they use the bathroom, and they disagree with him. Women, it seems, disgust him for being women, but there’s something bewildering about the range of characteristics he lumps together with this word.

In her long entry on “disgust,” Smith points out that, although adherents of universal emotion theory often point to disgust as a prime example of a basic emotion, there are, in fact, different types of physical disgust: core disgust (a “repulsion felt when something poisonous…comes near the mouth”); contamination disgust; and body-envelope violation disgust (which combines contamination with “an almost existential horror of the open body”). Smith is interested in how culture determines what is disgusting. She suspects that “the sense that something is ‘out of place’ might be more important to provoking feelings of disgust than the objectively dangerous.” In the eighteenth century, people began to use the word disgust for a growing number of emotions, including not just “physical revulsion,” but also “moral indignation.” Perceptively Smith writes: “disgust arises more powerfully when boundaries dissolve, meaning breaks down and things slide ‘out of place,’” Maybe it’s Trump’s sense that women, whether running against him in the election or speaking out against his conduct, are “out of place.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, disgust is one of the most effective words Trump could use to rally support, because, it turns out, how quickly or easily you feel disgust is a predictor of how you vote. Psychologist Yoel Inbar studied the correlation between sensitivity to the emotion of disgust and voting patterns, and found higher sensitivity linked to more conservative voting. For Trump, the word disgust is doing double duty: It’s a handy weapon to throw at the almost numberless things that upset him, and it attracts the many people whose experience of the world is filtered through strong, but not necessarily well-defined, emotions.

It’s hard not to look at all this disgust and see fear at the root of it. The New York Times analyzed 95,000 words from Trump’s speeches, interviews and rallies, and observed a “pattern of elevating emotional appeals over rational ones,” a tactic also deployed by politicians like Joseph McCarthy and Barry Goldwater. A conservative political consultant and writer, Reed Galen, characterized Trump’s speech at the Republican National Convention as “a fear-fueled acid trip designed to encourage older, white, disaffected voters to pull the lever for a time in America that no longer exists, if it ever did.”

Smith’s definition of fear explains another facet of Trump’s rhetorical power. Like disgust, fear is often considered a universal emotion. But, Smith notes, there is a difference between fear of bodily harm and more abstract fears, like that a loved one might leave you. Trump, however, conflates all these feelings. He describes the danger of terrorist attacks with the same fervor as his belief that the media has been unfair to him. According to the Times’s word analysis, “as much as he likes the word ‘attack’…he often uses it to portray himself as the victim of cable news channels and newspapers that, he says, do not show the size of his crowds.” Rationally, these things are different, but by flattening out distinctions between kinds of emotions, so that a woman breastfeeding is equated with beheadings by ISIS and the demise of democracy, he maximizes the appeal that he can make through a single, powerful emotion.

Just as our decisions are influenced by policies, they’re also influenced by appeals to emotion. Trump has been pounding the drum of fear loudly for months, and we’re all living in the reverberations. Of course, having more words for fear wasn’t going to stop Trump’s rise, but it might have given his opponents more effective ways to respond to him, and given voters a clearer sense of exactly what politics they are signing up for. Smith’s book shows how much we rely on, and are bound by, the words our particular culture gives us. Knowing the limits of what they describe, and the possibilities of other languages, should give us pause to think about what we really want them to say.