A powerful man asks you to his hotel room for a meeting. He has a reason; there’s always a reason. There are too many reporters in the lobby. He’s just in town for a little while. And although he’s never made you feel what anyone would call “comfortable,” you’ve met him before and you admire his work. But when you get to the room, and he grabs you, and begins kissing you, it is a shock. It’s only when he starts dragging you toward the bed that the reason he brought you here really becomes clear.

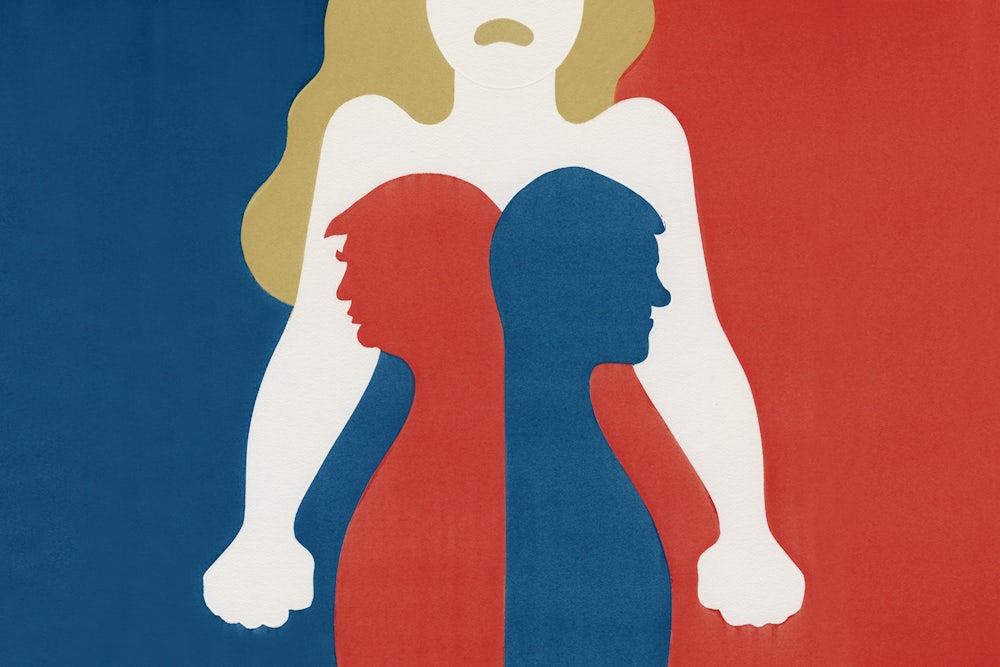

That’s how Summer Zervos, who was a contestant on the fifth season of The Apprentice, says Donald Trump assaulted her at a Beverly Hills hotel in 2007. It is also exactly how Juanita Broaddrick says Bill Clinton, then the attorney general of Arkansas, assaulted her during his 1978 gubernatorial campaign.

The parallels between the two cases reveal an uncomfortable truth. They not only mirror each other in their particulars, they also reflect certain attitudes about women and sex long held by many men in power. In the final weeks of the campaign, when a tape surfaced of Trump bragging that his celebrity entitles him to grab women “by the pussy,” Trump attempted a simple and telling defense: “Bill Clinton has said far worse to me on the golf course.” At that moment, the outcome of this year’s presidential race was made plain: Whichever candidate won, a man accused of some form of sexual misconduct would, in one capacity or another, occupy the White House for the next four years.

The tape of Trump, so many pundits declared on cable news, created an “unprecedented” situation. To some extent they were right. A recording of any public figure describing sexual assault in such unequivocal language is a rare find. In the days after the tape came to light, a dozen women came forward to assert that Trump’s words were, in fact, more than just words. In the past, some of their stories had been ignored or dismissed. But now that Trump’s own words supported their claims, major media outlets like The New York Times and CNN treated their allegations as presumptively legitimate.

It would be tempting to see this as a turning point in our attitudes toward assault cases. Women who accuse a powerful man were finally being given the benefit of the doubt. In an earlier era, many journalists would have treated Trump’s accusers as suspects: Why did they wait so long to come forward? Are they politically motivated? Those were some of the questions raised when Broaddrick made her allegations public in the late 1990s. Since then, a series of high-profile cases—notably the more than 50 women who have accused Bill Cosby of sexual assault—have altered our expectations of victims and clarified our sense of what constitutes consent and coercion. Zervos, in fact, is represented by Gloria Allred, the lawyer who took the lead in drawing national attention to Cosby’s accusers.

Yet it’s also true that Trump is a unique case, an outlier. Whereas we once looked for the “perfect victim”—say, a sexually inexperienced, middle-class white woman who could not be said to have given her attacker any “encouragement”—we have instead found in Trump an avatar of the “perfect attacker.” Few men in the public eye, especially those seeking high office, have flaunted their sexual aggression as nakedly as Trump. His lack of shame on the tape, plus his well-documented history of lashing out at women, all but confirmed what many would like to believe: that rapists are somehow different, a breed apart. That you can spot a man who is willing to commit a sexual assault by the way he talks and looks.

Bill Clinton was something else again: a charismatic and accomplished man who said all the right things and was married to a committed feminist. Allegations against him have not been taken as seriously, in part because he does not “look like” a sexual predator. Even today, Juanita Broaddrick’s case is often dismissed out of hand by major media outlets. Earlier this year, on the Today show, Andrea Mitchell called Broaddrick’s claims “discredited,” even though they have never been disproved. (NBC later scrubbed the online version of the report, muting “discredited,” while leaving the phrase “long-denied.”) Her detractors point out that Broaddrick once signed an affidavit denying her own claims, and only retracted the denial once Kenneth Starr offered her immunity from perjury charges. They also point out that Broaddrick appeared on behalf of Trump at his second debate with Hillary Clinton, and announced that she would vote for him.

Today when women come forward with allegations of sexual assault, we are urged to “believe them.” But for Democrats, Broaddrick’s story challenges that mantra—because belief in her runs counter to party allegiance. To voice confidence in her claims required us, in effect, to voice doubt about the first female presidential candidate of a major party. That paradox posed a net loss for American women. That a husband’s bad behavior could still detract from his wife’s success was intensely demoralizing. “Never imagined the election of the first female president would come down to a fight over who’s the real rapist,” New York Times reporter Amanda Hess tweeted before the second debate, “but here we are.”

The allegations of Bill Clinton’s and Donald Trump’s sexual misconduct inspired more than frustration in their supporters and glee in their opponents (or in Clinton’s case, in his wife’s opponents). Pro-Trump or Never Trump, with Hillary or against her, the revelations allowed people on both sides to feel virtuous. And virtue was in short supply, as the presidential contest grew darker and angrier. Trump’s insult-comic routine, his mocking of the disabled, his bald racism, the violence of his rallies— all of it surfaced every bad thing America believes about itself. So the widespread disgust at Trump’s sexual boasting brought with it an undercurrent of relief. Everyone was desperate to feel something better than what they were feeling, to rise above the sleaze. Defending a victim of sexual assault allowed each of us to make one last grab—no pun intended—at human decency.

While the election was underway, it was difficult to discuss any of this honestly, in large part because liberals did not want to risk tipping the electoral math in Trump’s favor. But we should acknowledge the parallels that emerged during the campaign’s final weeks. We do not have to believe that Bill Clinton’s behavior is the equivalent of Donald Trump’s. We do not have to believe that Bill Clinton is the same as Bill Cosby. We simply have to accept what has been apparent since at least 1992: that Bill Clinton was never afraid to use the allure of his power as a tool of seduction. Much worse, he has, at every opportunity, opted to save himself at the expense of the women who tried to report any bad experience with his alleged charms.

Not all of those experiences amounted to the kind of assault that Juanita Broaddrick described, but they are troubling nonetheless. Take the case of Monica Lewinsky, where the facts are relatively uncontested. Lewinsky readily admitted that her relationship with Bill Clinton, whatever its sexual and emotional contours, was consensual. But from the moment he was forced to confront his actions in public, Clinton did everything he could to undermine and discredit her. As far as I know, he has yet to admit to any wrongdoing on that score, though he has acknowledged that the relationship itself was inappropriate.

It’s curious to remember that at the time, Clinton elicited sympathy from prominent women, many of them declared feminists. In 1998, the New York Observer assembled a panel of luminaries to dissect “the only topic anyone talked about all week,” which led to plenty of cruel jokes about Lewinsky. “My dental hygienist pointed out that she had third-stage gum disease,” said Erica Jong, the author of Fear of Flying. Lewinsky’s name is still used as the butt of jokes: New York magazine recently compiled more than 40 rap lyrics that reference her, including a song titled “Splashin over Monica.”

Only two years ago did the story America told itself about Lewinsky begin to change. In 2014, she published an essay in Vanity Fair about the ridicule she endured after the scandal. “It may surprise you,” she wrote, “to learn that I am actually a person.” At least in some quarters, it began to dawn on people that something more complicated than a sordid sex scandal had befallen Lewinsky, something not quite reducible to, as she put it, a blue dress and a beret.

And yet, all these years later, we still don’t have a word or a phrase for what happened to Lewinsky. She got caught in a destructive vortex of power and sex that no one knew how to talk about. Even after this election-year parade of horribles, even after all our sober public pronouncements about sexual assault, it isn’t clear that anyone knows how to talk about it. The vocabulary simply doesn’t exist. The call to “believe women” was always a gesture at that reality. It was a demand that, at the very least, we learn a sexual assault victim’s terms for her own experience before we render judgment.

Over the past few weeks, it seemed that America was ready to conduct a long-delayed reckoning on issues of power, gender, and sexual assault. But in practice, now that the campaign is over, we’ll likely find it easier to put the whole nasty business behind us. We will congratulate ourselves on a discussion about sexual assault that we didn’t actually have, in the false hope that a season of profound discomfort is finally over.