Many Americans value environmental protection and want to see more of it. But Jill Stein, the Green Party presidential candidate, is drawing only 1 to 3 percent in recent polls, even in an election where many voters dislike the major candidates and are looking for alternatives.

Stein certainly has worked to differentiate herself from the two major party candidates. In July she asserted that electing Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton—probably the choice of most pro-environment voters—would “fan the flames of … right-wing extremism,” and be as bad as electing Donald Trump.

While Stein makes anti-establishment statements like this, her German counterparts have been advancing a green agenda in local, regional and national government for the past 30 years. Most recently, Winfried Kretschmann was reelected this year as head of government in Baden-Württemberg, one of Europe’s technologically and industrially most advanced regions.

I grew up in Germany and have taught about Germany and Europe in the United States for the past 15 years, so I have seen Green Party politicians at work in both countries. In my view, there are two reasons why the U.S. Green Party remains so marginal. Structurally, the American electoral system is heavily weighted against small political parties. But U.S. Greens also harm themselves by taking extreme positions and failing to understand that governing requires compromise—a lesson their German counterparts learned several decades ago.

One movement, two electoral systems

Both European and North American Green Parties evolved from activist movements in the 1960s that focused on causes including environmentalism, disarmament, nuclear power, nonviolence, reproductive rights and gender equality. West German Greens formed a national political party in 1980 and gained support in local, state and federal competitions. Joschka Fischer, one of the first Greens elected to Germany’s Bundestag (parliament), served as the nation’s foreign minister and vice chancellor from 1998-2005.

The German Green Party’s rise owed much to the country’s electoral system. As in many continental European democracies, political parties win seats in German elections based on the percentage of voters that support them. For example, a party winning a third of the popular vote will hold roughly a third of the seats in the parliament after the election. Proportional representation makes it possible for small parties to gain a toehold and build a presence in government over time.

In contrast, U.S. elections award seats on a winner-takes-all basis. The candidate with the most votes wins, while votes cast for candidates representing other parties are ignored. As a result, American voters choose their leaders within a de facto two-party system in which other parties often have trouble even getting their candidates’ names onto ballots.

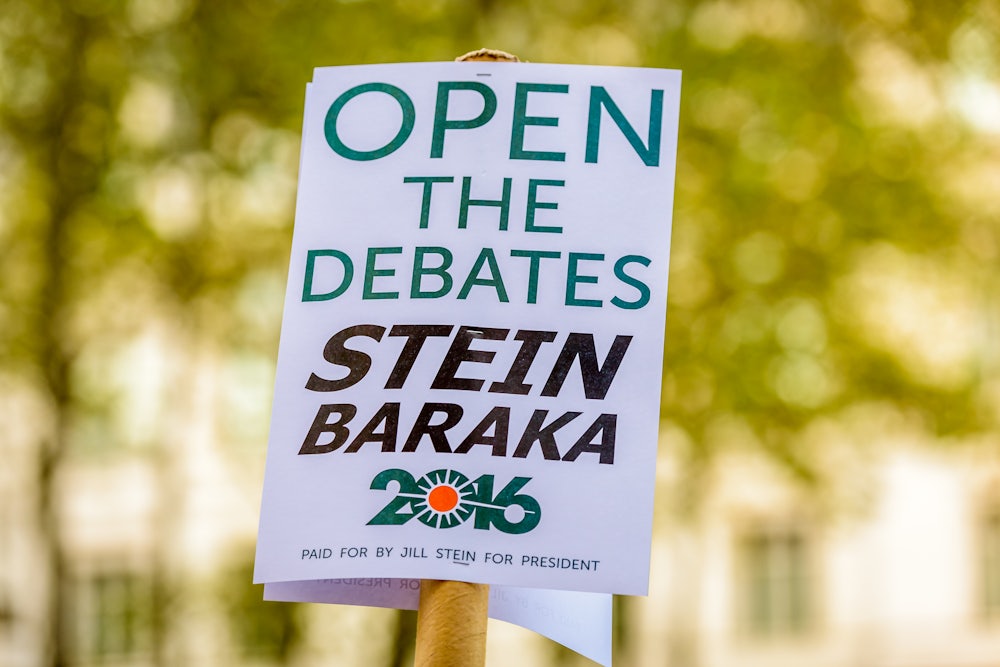

U.S. Greens have won only a handful of state-level races, and have never won a congressional seat. Their greatest success came in 2000, when Ralph Nader and Winona LaDuke won 2.7 percent of the popular vote in the presidential election. Many observers argued that Nader’s only real impact was to throw the election to conservative Republican George W. Bush, but Nader and many of his supporters strongly disagreed, and the question of whether challengers can act as more than spoilers in U.S. elections remains controversial today.

Purity or compromise?

As green politicians have helped to shape political priorities in Berlin, Brussels and other European capitals and regions, many observers have debated whether these former activists are selling out by participating in the political process—and whether joining that process helps or hurts the green movement.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Green Party conventions in Germany were dominated by fierce infighting between moderate “Realos” (realists) and radical “Fundis” (fundamentalists). The Realos, who prioritized electability over ideology, eventually prevailed.

In order to graduate from an opposition party to a ruling party that controlled cabinet posts, German Greens had to develop a capacity for compromise. To gain power, they had to form coalitions with center-left Social Democrats. But coalitions require consensus—especially in parliaments with proportional representation.

Interacting with centrist politicians, unionists, church representatives and the media taught Realos to act less like activists and more like politicians. In 1998 the Green Party formed a so-called red-green coalition with the Social Democratic Party (SPD), a party that has traditionally championed the working class, and won a large majority in the Bundestag.

Working through this alliance, former activists initiated reform of an antiquated immigration and citizenship law and worked toward recognition of same-sex unions. They implemented an environmentally driven tax code and brokered a deal with the nuclear energy industry to cancel projects for new plants and phase out nuclear power by 2022.

Many Green Party supporters thought Realos were too eager to compromise. Some even physically attacked their party leaders when the coalition government supported use of military force in a NATO-led campaign against Serbia in 1999. Many critics viewed this decision as the remilitarization of German foreign policy under the leadership of Joschka Fischer of the Green Party, then serving as Foreign Minister.

However, these compromises did not erode broad public support for the Greens. On the contrary, in 2002 the red-green coalition was reelected and the Green Party received more votes than it had in 1998. When the coalition government broke down in 2005, it was due to Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s lack of leadership within his own SPD.

Although the Green Party has not regained control of Germany’s federal government since 2005, its positions have become part of the nation’s mainstream political culture. Notably, after the 2011 nuclear plant meltdown in Fukushima, Japan, a center-right German government decided to accelerate the phaseout of nuclear power in response to rising public concern. To reach this goal, Angela Merkel’s centrist government has implemented an ambitious policy bundle known as the Energiewende that seeks to transition Germany to a nonnuclear, low-carbon energy future.

Massive governmental support for alternative energy sources has encouraged Germans, especially in rural areas, to invest in solar power, wind turbines and biomass plants. These green policies did not harm, and may have buoyed, Merkel’s status as one of the most popular German chancellors prior to this year’s controversies over immigration. Germany reformed its renewable energy law this year in response to new European Union rules governing electricity markets, and will shift from subsidies to market-based mechanisms, but the Energiewende remains highly popular.

No third lane

There is no easy way for the U.S. Green Party to emulate its German counterparts. Because the American political system makes it difficult for third parties to participate, Green Party candidates do not have opportunities to learn the trade of politics. They have remained activists who are true to their base instead of developing policy positions that would appeal to a broader audience. By doing so, they weaken their chances of winning major races even in liberal strongholds.

As a result, green ideas enter American political debates only when Democrats and Republicans take up these issues. It is telling that major U.S. environmental groups started endorsing Clinton even before she had clinched the Democratic presidential nomination over Bernie Sanders, who took more aggressive positions on some environmental and energy issues during their primary contest. And although Sanders identifies as an environmentalist, he sought the Democratic Party nomination instead of running as the Green Party candidate.

This suggests that running on a third-party ticket in the United States is still not a winning route to shaping a message aimed at a broad electorate. Instead, climate change, dwindling energy resources and growing human and economic costs from natural disasters will do more to promote ecological consciousness and political change in mainstream America than the radical rhetoric of the U.S. Green Party.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.