The terrorist attack earlier this month in New York followed a pattern that has become at once predictable and puzzling. A troubled young man, failing to make something of his life, grows alienated from his family, community, and country. He embraces a radical jihadist ideology that promises redemption in return for murder, then proceeds to act on that ideology by trying to kill as many people as possible.

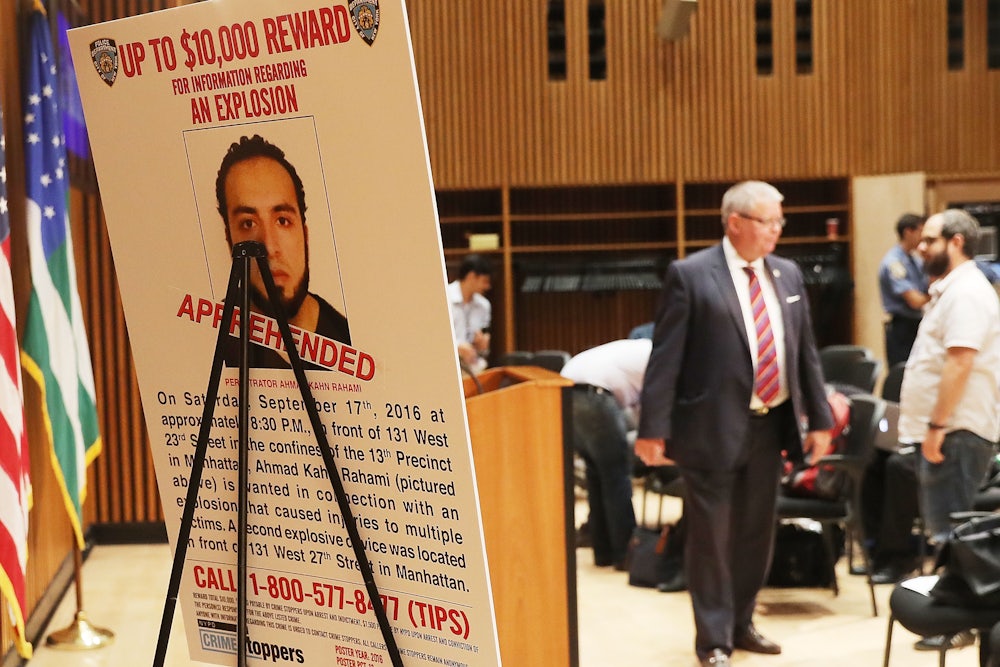

Ahmad Khan Rahami was the latest suspect in a long list of young males, radicalized online and abroad, who have attempted to carry out mass carnage in the name of Islam. More than 100 people have been arrested in the United States since 2014 for supporting ISIS. Two hundred and fifty Americans have traveled or attempted to travel to ISIS territory. Compared to Europe, these numbers are quite low, but it is the possibility of a single catastrophic attack that makes the terrorist problem so acute and the biographical patterns of recent attackers so alarming.

Following every terrorism-related incident there is a frenetic search for clues to explain the attacker’s path to radicalization. Almost always, it becomes evident that the jihadi in question reached a mental breaking point that preceded his rebirth as a self-described martyr. Something in the person cracked. This fracturing of identity, a dismemberment of the self, led to what psychologists call a “cognitive opening.” An existential vacuum was created in their minds, allowing the germ of jihadist ideology to implant itself, metastasize, and transform the ordinary man into a mass-murderer.

This was the trajectory of Rahami: he fathered a child while still in high school, dropped out of college, and physically abused his family. It was the trajectory of the Pulse night club shooter, Omar Mateen: violent since his middle school years, dismissed from his job, tortured by feelings of homosexuality. It was the trajectory of countless European jihadis who were uniformly loners, anti-socials, petty criminals, and, in most cases, drug dealers or heavy drug users. (“He often slept during the day,” said the wife of one of last year’s Paris jihadis. “The number of joints that he smoked was alarming.”) It’s a familiar narrative of alienation fueling extremist religiosity, which in turn fuels extreme carnage.

It is facile to pin the blame on Islam or Muslim culture alone. Rahami’s father told the FBI that his son was engaged in terrorism, and Muslims themselves are the greatest victims of jihadist violence. Researchers who study the radicalization problem note that terrorists are created in basements, not prayer halls. And a significant number of Muslims who become radicals were not born into Islam but converted in adulthood, evidently seeing in the religion a path to internal harmony.

The psychological element in these terrorist crimes has prompted a fresh look at how to confront them. Last year, the White House held a summit on Countering Violent Extremism, pledging to work with local communities to stage an intervention on suspected radicals before they commit crimes. But by far the most common buzzword for how to deal with jihadism is “de-radicalization,” a process by which an individual with terrorist sympathies is given counseling, therapy, and intellectual sessions to convince him to abandon his radical views.

A number of European and Middle Eastern countries have implemented de-radicalization programs already. The most prominent program is run by the Saudi government. Not typically known for its humane treatment of prisoners (or anyone else), the Saudis have special prisons for convicted jihadis that provide the inmates with big-screen TVs in their rooms, free health care, a monthly stipend, art therapy, and access to gyms and swimming pools. While the detention centers have the look and feel of a luxurious spa, their purpose is clear: to rid the jihadis of what the Saudis call “ideological sickness” by bringing in psychologists, therapists, and clerics to teach the “correct” Islamic view on matters of law and violence.

It’s a tough proposition because the ultra-conservative Saudi kingdom and ISIS are ideological cousins—differing only in their methods. The Saudis initially claimed that their program had a 100 percent success rate, but a number of graduates from their de-radicalization program have joined Al Qaeda. The recidivism rates are difficult to ascertain, but in any event, the scale of the Saudi program and its geographical location make it sui generis.

This past April, a federal judge in Minnesota created the first de-radicalization program in the United States for four Minnesotans convicted of supporting ISIS. The jihadis will meet with a leading psychology expert who will assess their motives and histories, and work with them to understand why they were drawn to ISIS. This will be the basis from which, it is hoped, the individuals in question will be purged of their jihadist fantasies. While the program is in its beginning stages, it will be watched by prosecutors and judges across the country to see if it can be replicated in other cities.

But there are a number of reasons to be cautious—even suspicious—of any such efforts to deprogram extremists. None of these de-radicalization efforts have been proven to be effective, according to studies. A RAND report concluded, “There are not enough reliable data to reach definitive conclusions about the short-term, let alone the long-term, effectiveness of most existing de-radicalization programs.”

This should not come as a surprise, even with all the years that have passed since 9/11 and all the countries that have instituted such top-down de-radicalization programs. Jihadis hijack the Islamic texts in pursuit of glory, narcissistically ventriloquize the supposed grievances of a billion Muslims, and shamelessly blame the blood they shed on America’s sins. I say “shameless” because of the non-sequitur that jihadis employ: Both Ahmad Khan Rahami and Omar Mateen justified the mass targeting of innocents, on the streets of New York and in an LGBT bar, because the United States was bombing ... ISIS, a terrorist group that enslaves its ideological opponents and slaughters women and children. It is to be expected that efforts to de-radicalize such disturbed individuals would meet roadblocks.

Of course, there are outlier cases. One American man who was a recruiter for Al Qaeda found solace in the works of John Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers in prison, and now teaches at George Washington University’s extremism program. But his path out of the dark tunnel of extremism was a self-generated one, and therefore anomalous. Any man or woman, given the great texts of philosophy and history, can annex wisdom out of books and change what they believe. It is in this sense that Hannah Arendt called the act of thinking “a dangerous activity.” The ability to see more than a single shade of truth, and to question the pretensions of all received authority, opens new vistas. But thinking is dangerous precisely because it undercuts any solid, holy crutch that can be leaned on for support. The problem with jihadis is that they worship the very opposite of critical thinking—a cheap and all-encompassing ideology that provides easy answers to life’s most difficult questions.

Then there is the question of principle. A de-radicalization program is, in effect, a brainwashing scheme—or in some cases, a reverse brainwashing. Should the state, with its assorted arms of power, be in the business of indoctrinating acceptable views into people who are perceived to be devoid of them? It is one thing to rehabilitate convicts by offering them therapy, altering their behavior, and helping them reintegrate into society; it is quite another to try to reorient an adult’s beliefs about the divine so that he recognizes the virtues of tolerance and respect.

Instilling an ethical and moral code is primarily the responsibility of families and communities. Most of all, it is the responsibility of the individual. To figure out one’s existential dilemmas, and to suffer the pain of uncertainty and confusion, is part of what it means to be a human being. Jihadis abandon this journey and opt for an extremist, millenarian ideology that instantly gratifies their searching mind. In this way, jihadism is more like an analgesic than a coherent doctrine, curing these young men of their internal agony, consoling their rootless existences, and paving the way to a heavenly utopia.

Freud thought that human beings clung to old religious ways because we never stopped being children yearning for a father figure. There certainly seems to be a universal urge among these radicals to prove their masculinity, to validate their self-worth by submitting themselves to a barbarous patriarch. Imagine the internal loathing it must take to do this. To slaughter one’s neighbors and fellow citizens in cold blood, rationally planned, detailed, and executed. To indict one’s fellow Muslims in an unprovoked crime of resentment. To desire turning a billion of one’s co-religionists into co-conspirators by speaking in their name. Jihadism as an ideology is murder leading to paradise. Jihadism as a psychological state is the outward projection of an inner hell. It is a totalizing condition, one that cannot be exorcised by a visit to the therapist.

What makes jihadism so alluring in the first place is a desolate, depressive state of mind. It is not a psychological disorder in the clinical sense that drives a young man to a violent religious cult. Rather, it is what the cult provides—a lifeline and death wish to which an anguished mind may cling. Look no further than the descriptions of Rahami, which mirror those of ordinary suicide cases before they attempt to take their lives. “He was always in high spirits,” one of Rahami’s former classmates said about him. “Literally a ray of sunshine.” The Muslims least likely to turn into radicals are the happy ones; they have no need for a cult to affirm their value. This world is enough for them.

Karl Marx’s most quoted line is about religion being the opium of the people. But a more nuanced idea comes in the following paragraph, when Marx says that to demand that individuals abandon their religious illusions is to demand that they “abandon a condition which requires illusions.” The conditions—social, familial, sexual, emotional—that give rise to jihadism are not ones that can be cured by a government-mandated de-radicalization program. Drone strikes or longer prison sentences will not alleviate the misery of those conditions, either. But it is these conditions, the ones that have made a deathly ideology more appealing than the arduous task of daily living and suffering, that will need to be changed.

Unfortunately, there are no quick or easy answers here. But Muslim parents and American communities with Muslim populations can start by nurturing those kids who seem to be drifting off, and listening to those who seem to be lost. Because the appeal of jihadism is finally a rebuke of traditional Islam itself. What hope do these young Muslim men find in their seething holy gangs, real or virtual, that they cannot find in the mosque, or at the dinner table with their parents? Why are these young men so driven to torment that they seek refuge in the darkest of alleys? What illusions do they crave, and why do they remain so unfulfilled by their surroundings?

“They never taught us the first thing we needed to hear,” a Muslim friend and artist said to me a few weeks ago, as we were discussing our similar religious upbringings. He was referring to the mosques and family elders we knew, the ones who to us seemed so far from our lived realities that they may as well have resided on another planet.

What was it that we hadn’t been taught, I asked my friend.

“They never taught us to love ourselves. To accept ourselves. They only told us to be afraid.”

It may be a cliche to offer love as a solution to hatred. But without it, a lost generation will continue to fester—one that sees violence as an end to itself. And that would be the ultimate illusion.