Years ago, there was an old guy in my neighborhood named Pete. His hair was white and disheveled, and he liked to wheel his small shopping cart up and down the street and hand out political flyers to everyone he met. Some days the flyers were about the dangers of nuclear power. Some days they were about the perils of free-trade agreements. But they were always handwritten, they always took up both sides of the page, and there was never a margin in sight. For Pete, margins were a missed opportunity, a plot by the establishment, an artificial convention created by a world that mistook the urgency of the situation. The truth has no use for margins.

Bernie Sanders is a little like Pete. He doesn’t have a shopping cart, and his political positions are significantly more coherent. But like Pete, he has no patience for anything that threatens to distract him or others from the pressing matters at hand. When I arrive at his Senate office for an interview, he does not want to chat about the last time we met, at a tribute in Vermont to the late journalist Michael Hastings. He does not want to look back at his historic campaign for the presidency and consider what he might have done differently. He does not want to talk about Hillary Clinton’s shortcomings or the incivility of some of his supporters. He does not mention that tomorrow is his seventy-fifth birthday. He wants to talk about policy, and the nuts and bolts of organizing, and whatever else is needed to bring a greater measure of justice and equality to human affairs. He lives by the Marxist-Calvinist tradition of everything for the cause. He doesn’t have time for roses. Too many people need bread.

This single-mindedness of purpose is at the very heart of his appeal. Other people live in this world, and abide by its niceties. Sanders looks forward to the world yet to be, the world as it should be. He set out to lead a revolution, and he nearly succeeded. His agenda is a cross between Das Kapital and Deuteronomy. He rails against the Trans-Pacific Partnership with the same hatred that the rest of us reserve for the New York Yankees, or the New England Patriots, or some other, more leisurely expression of American empire.

Now, after laboring for years as a lone voice on the left, Sanders suddenly finds himself speaking for millions. It’s an unexpected role, and not without its pitfalls. Having won twelve million votes in the Democratic primaries—a showing that exposed the deep rift between younger voters and the party establishment—Sanders faces a new challenge: how to continue to pressure the party from the left without tearing it apart in the process. The internal tensions have been apparent from the start: In August, when Sanders launched his new organization, Our Revolution, key staffers resigned in protest over the group’s structure, which permits it to accept contributions from billionaires without revealing the donors.

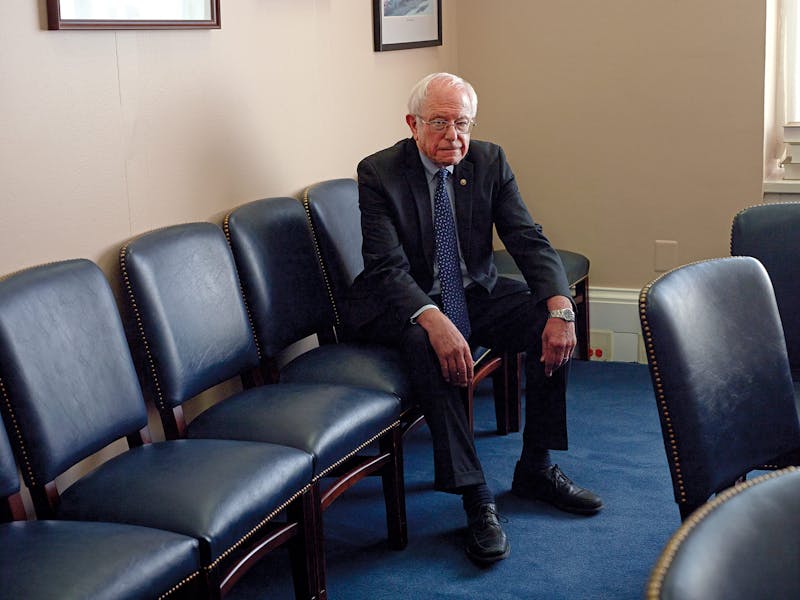

On a hot afternoon in September, we speak for nearly an hour in his office on the third floor of the Dirksen Senate Office Building. Whenever the conversation turns to something he doesn’t care about, Sanders doesn’t nod politely, or find a way to change the subject. He looks away, or scowls, or dismisses it out of hand. But when the talk turns to tax policy, or student debt, or the minimum wage, he leans forward and speaks with passion and urgency. He looks like a man who sees a margin that needs filling.

Let’s start with a postmortem on the extraordinary campaign you ran. You came very close to defeating Hillary Clinton, who’s the closest thing America has to a political dynasty. Looking back, is there something you wish you’d done differently? Something that might have put you over the top and enabled you to win the race?

Well, I think every day we all wish we had done something different yesterday—certainly in something as complicated as a presidential campaign. Of course there were things I wish we had done differently. But at the end of the day we did much, much, much better than anyone dreamed we could have. People who study the campaign will see that it was a very, very effective campaign. Should we, in retrospect, have done things differently? The answer is, of course we should’ve.

Give me an example.

I don’t really want to do that type of postmortem. It doesn’t matter. We put together a great campaign with some fantastic people, given the time constraints. But the difficulty is that in a campaign, you’re moving very, very fast. You are starting with three or four people, and then within a few months suddenly going up to a thousand people in many, many states throughout this country, hiring people you really don’t know, trusting that they will be able to do the kind of work they need to do. Corporations do this slowly and steadily, but you don’t have that option in a campaign. And of course you’re running not one campaign, you’re running 50 campaigns, and hiring this state leader here and that one there. So not every person we brought on was of the quality, in retrospect, that we would’ve liked to have had.

In retrospect, you also always think, “Should I have spent more money in a state on television? Should we have spent less money in a state on television?” There’s always that kind of Monday-morning quarterbacking. But at the end of the day, we showed that there are millions of people in this country who are sick and tired of establishment politics, who want real change, and who are prepared to stand up and fight for that. My hope is that that movement continues to go forward.

After 35 years in politics, this was your first campaign at the national level. What surprised you most about the whole process of running for president?

One of the disappointments—not really a surprise—was the media. The very great reluctance of the media to cover the serious issues facing the American people. There was a study that came out a couple of months ago, which showed that only 11 percent of the campaign coverage dealt with issues. For much of the media, coverage was all about the ups and downs of a campaign day, which obviously benefits somebody like Donald Trump very, very much. He’s great for the media, because you don’t know what he is gonna say. So I found it disappointing that we had a hard time getting some of the very serious issues we were trying to raise out through the media.

On the other hand, I was also surprised and gratified that CNN would sometimes cover an entire rally. That would give us an opportunity to beam out directly, through television, to people in many parts of this country who had never heard a progressive message before.

The other thing that I would say is that I left the campaign, quite honestly, more optimistic about American politics than when I went in. We went to 46 states, and I saw great people. That’s not just rhetoric—that’s reality. Just wonderful, wonderful people in all walks of life trying to do the right thing.

You fared badly among black voters during the campaign. Fewer than one in four supported you. Why do you think that is?

The answer is not complicated. The answer is a fairly simple one: Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton have developed very strong roots within the African American community over decades. They are very popular within the black community, and that’s that. Among older African American women, it was like ten to one. We were really getting decimated. But by the end of the campaign, we were winning a majority of young black and Latino voters, which was very, very impressive. In fact, in some communities we wound up winning the Latino vote overall.

I’ve spoken with longtime supporters of yours who feel that you lost in part because despite your own record in civil rights, you didn’t seem comfortable talking about race in a way that—

[Interrupting] OK, see, this is an issue I’m not really—what I don’t want to do is get into me.

I’m not raising this to talk about you. I’m interested in hearing your take on racism. Do you see it as primarily a class issue—a by-product of economic injustice? Or is it a separate and distinct problem of its own?

It’s a complicated answer. It’s a good question, but I prefer not to get into it right now. [Stony glare, followed by silence.]

All right, let’s talk about the young voters you mentioned. During the primaries, almost three-quarters of voters under the age of 30 cast their ballots for you. What do you say to your younger supporters who don’t plan to vote for Clinton because they see her as too establishment-oriented?

Look, I ran against Hillary for over a year, so I understand where she is coming from. For me, this is not a tough choice. I am a United States senator, and I know what would happen to our government if Donald Trump became president. I think Donald Trump is the worst candidate for a major party that has surfaced in my lifetime. This guy would be a disaster for this country and an embarrassment to us internationally. A man who is a pathological liar. Somebody who, to the degree that he deals with issues at all, changes his position every day. That is clearly not the kind of mentality we need from somebody who is running for the highest office in the land.

What is particularly outrageous and disturbing is that the cornerstone of his campaign is based on bigotry—trying to turn people against Mexican-Americans or against Muslims or against women. To my mind, it’s very clear that Donald Trump would be an incredible disaster to this country, and I will do everything I can to see that he is defeated.

But is there a case to be made for Hillary, solely on her own merits?

On a number of issues, I believe Hillary Clinton’s positions are quite strong. I was happy to negotiate an agreement with her in the party’s platform which said that she would support making public colleges and universities tuition-free for families making $125,000 or less. That is pretty revolutionary. That will not only transform the ability of people to go to college, it will have an impact on kids in elementary school today who know that if they study hard, they can get a college education. She and I also agreed to a doubling of the expansion of community health centers. That’s tens of millions more people who will have access to primary health care and dental care and low-cost prescription drugs and mental health counseling. I want to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour, and I think Clinton is open to moving in that direction, to at least $12 an hour. She supports infrastructure projects that will put millions of people back to work. She understands the significance of not acting on climate change, while Donald Trump does not believe that climate change is real, which is a real threat to the planet.

So what I would ask people is to take a hard look at (a) what a Donald Trump presidency would mean for this country, which in my view would be a disaster, and (b) how Clinton’s views on a number of issues are fairly good. That is what we should be focusing on—not the personalities of the candidates, but what their policies will do for the middle class and working families of this country.

You certainly played a major role in pushing Clinton to the left on some key issues, at least in the party’s platform. But many of your supporters don’t believe that Hillary really supports those positions or will make good on those promises. They see it as something she did in the platform to appease the left.

I think that Hillary Clinton is sincere in a number of areas. In other areas I think she is gonna have to be pushed, and that’s fine. That’s called the democratic process.

Right now, you have a majority of Republicans—of Republicans—who believe we should raise taxes on the wealthy. Do I think Clinton is prepared to do that? Yeah. Do I think she is prepared to do away with loopholes to get rid of outrageous tax breaks for large multinational corporations? Yeah, I do. Do I think she is serious about climate change, and that we can push her even further? Yeah, I do. Do I think that under Clinton we will raise the minimum wage? Yeah, I do. I’m not quite sure it will be 15 bucks an hour, but it will bring millions of people out of poverty.

Through the work of millions of people, we created a Democratic platform which is far and away the most progressive platform in the history of the United States of America for any political party. Our job the day after the election—and hopefully after Clinton is elected—is to make sure that that platform is implemented.

So what I would ask of young people is to turn off CNN. Let’s assume that Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders and you and everybody else are not perfect human beings, all right? Let’s take a look at the needs of ordinary people and which candidate will be better on that as president of the United States. On that approach, there is no debate to my mind that we should elect Clinton.

Let’s talk for a minute about that post-election process of putting pressure on Hillary. At the Democratic convention, things turned ugly. Some of your supporters disrupted speeches and heckled opponents. And it hasn’t stopped—at your latest rally for Clinton, some of your backers showed up to chant “Never Hillary.” It seems to me—

When did this happen?

On Labor Day, at your event with Hillary in New Hampshire.

You see, it’s interesting that you mention this. Was this written up? This is again the media. We had 400 or 500 people there. It’s true that there were a few people there from the Green Party, but I don’t recall hearing anything.

Well, let’s stipulate that only a small number of your supporters have engaged in that kind of disruptive behavior. Even so, it seems to me emblematic of the challenge you face. If Hillary wins, you need to challenge her strongly from the left to achieve your goals. But you also need to make sure that happens in a way that doesn’t tear the party apart or create an opening for the right. Is that a tension that’s controllable?

Our campaign took on virtually the entire Democratic establishment. We had the endorsement of one United States senator. We had six members of Congress. We had zero governors, zero large-city mayors, zero state party chairs. That is what we took on. And what we showed is that there is an enormous distance between what goes on here, in the Democratic Party, and the real world out there. So the Democratic Party, if it is going to survive, is going to have to open its door to people who are a little bit louder, a little bit coarser than the fine men and women who go to the $10,000-a-plate fund-raising dinners. They are going to have to let other people in America in the door and start representing their interests.

The only way you make change is by rallying large numbers of people to stand up and fight back. And the day after the election, that is exactly what I intend to do. My job is to help rally the American people and say, “Yeah we’re going to make public colleges and universities tuition-free, create a massive jobs program, rebuild our infrastructure, establish pay equity for women, raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. We are going to double funding for community health centers and move toward a Medicare for all, single-payer program of health care. We are going to deal aggressively with climate change. We are going to demand that the rich and large corporations start paying their fair share of taxes.” Every one of those issues is a popular issue. And whether the folks here in Congress like it or not, the way change comes about—the way we were able to write the Democratic platform—is not because everybody liked Bernie Sanders. It’s because they realized, “Oh, we better do this, because there are people out there who believe in this.”

I can’t think of a presidential candidate who has ever succeeded at turning their campaign into an ongoing movement. How will you succeed where everyone else has failed?

I think your statement is probably right. It is very difficult. What we have done is taken the campaign and transferred the nuts and bolts of that, in a much reduced fashion, into an organization called Our Revolution. I am not a part of that. Legally, as a United States senator, I can’t be. But the goal of Our Revolution is to get people involved in the political process, from school board on up to the United States Senate. We are going to be working with organizations like MoveOn and trade unions to help people financially and give them the confidence they need to successfully run for office. We will also be working on state ballot items that deal with terribly important issues: Citizens United, automatic voter registration, controlling the cost of prescription drugs, Medicare for all.

In some ways, you’re talking about building a modern political machine. Democrats used to have a structure that did exactly what you are describing—getting people elected, from the school board and dog commissioner on up. That really doesn’t exist anymore in the fashion you’re talking about.

It’s a challenge, and I don’t want to suggest that it’s easy. One of the great crises we face—and what the campaign demonstrated—is how far out of touch most Democratic leaders are with their constituents. That we can go into state after state and take on the entire Democratic establishment, in some cases win landslide victories, tells you that the gap between the Democratic leadership and grassroots folks is very, very wide. It is enormously important that we revitalize American democracy, that we get people thinking about the issues that impact their lives and their families’ lives and their neighbors’ lives, and start figuring out the route forward to address those issues.

Now, you may think that’s pretty simple. If you are not feeling well, you go to the doctor, right? The doctor makes the diagnosis and provides the treatment. And yet that is not what we do in talking about politics. That is certainly not what television does in talking about politics, and Americans know it. What are the problems facing the country? Do we really even discuss them? One of the successes of our campaign is that we hit a nerve and said, “Yeah, these are the issues. Why isn’t anybody talking about them?”

When you asked before about economics and race—well, we have more people in jail than any other country on earth, and they are disproportionately African American and Latino and Native American. We have youth unemployment rates in communities which are 30, 40, 50 percent, yet we are shocked, just shocked, that when kids have no constructive opportunities to earn a living, they engage in illegal activity. Who talks about that? Who talks about the reality of what goes on in Native American reservations in this country? I have sat in a room with people who make $7.25 an hour, OK? You don’t see that on television. Somebody’s got to talk about what poverty means in this country, and how you cannot live on $8 or $9 an hour.

So the strength of the campaign was that people turned on the TV and said, “Oh my God, somebody is talking about my life. Somebody is talking about what this country can become. Somebody is asking why the United States can’t have a national health care program when every other major country on Earth does.” It’s about putting the questions out there, getting people to think about it and say, “OK, I can do something about it.”

And in the midst of all of that, you are going to have to take on the Koch brothers and the billionaires who are spending huge sums of money to buy the elections. That’s also an issue that’s not being talked about. You tell me—do you watch television? Tell me if I am wrong. How often do you hear the words Citizens United? And you know why? Because Citizens United is the best thing that ever happened to television. Is it not? They are making God knows how much money.

When it comes to campaign finance, journalists always talk about who gives the money, and which candidates receive the money. But they almost never talk about where the money ends up. Candidates don’t keep the money that flows into political campaigns. Most of it winds up being pocketed by major media companies. It ends up in advertising.

It ends up in advertising, primarily television. Best thing that ever happened to television. So you need to break through that crap, break through the media, and get people to play an active role in resolving the issues that impact their lives and creating a democratic society.

Your plans for Our Revolution remind me of what the Moral Majority and the far right did between Barry Goldwater’s loss in 1964 and Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1980. They did a lot of work at the local level to run people for school boards and get local candidates to focus on the issues that mattered most to them. That was a successful movement that emerged from a losing campaign—one that changed the course of a major political party.

That is absolutely right—you have to start from the bottom on up. What the Democrats do now is, “Oh, we’ve got an election—how do we go out and raise money from rich people to buy television ads and pay for consultants so we can elect somebody to the United States Senate?” I understand that—that’s one way to do it. But there is another, more fundamentally important way, and that is to build a movement of people. The Christian Coalition in fact did do that.

I don’t think that anybody would debate that the gap between Democratic leadership and grassroots America is very, very wide, and that has a lot to do with the fact that over the last 30 to 40 years, Democrats have spent so much time raising money. People are just astounded by the amount of time somebody like Hillary Clinton spends talking to 20 people so she can walk away with a few hundred thousand dollars, rather than relying on ordinary people.

One issue that will affect working people is the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the trade pact being pushed by President Obama. You tried to get a commitment in the party’s platform to not hold a vote on TPP, but you were unsuccessful. Are you worried that there is going to be an attempt to pass it in the lame-duck session of Congress?

Yes. The president has been adamant in his support for the TPP. I spent a half-hour with him on the phone talking about the issue. He is dead wrong, but he feels very, very strongly about it.

The corporate world virtually never loses on trade. Since I’ve been here, they always win. Wall Street, drug companies, corporate America—that is a very heavy-duty group. When they push with their unlimited sums of money, they can make things happen. I will do everything that I can to rally the American people to understand that TPP is a continuation of disastrous trade policies, and that it should not be passed.

So why does President Obama think it’s a good idea?

He sees it as a geopolitical issue. He does not pretend, as previous presidents have, that this is going to create all kinds of jobs in America. His argument is that if you abandon the TPP, you’re gonna leave Asia open to Chinese influence.

So he’s not making a NAFTA argument—that a rising tide of trade will lift all boats.

Right—that mythology seems to have disappeared. But one of the interesting things about the TPP, in particular, is not just that it’s gonna force American workers to compete against people making pennies an hour in Vietnam or slave labor in Malaysia. It also includes an investor-state dispute system. If my state of Vermont, or the United States government for that matter, passes a piece of legislation designed to protect the health of the American people or the environment, then that government entity could be sued by a multinational foreign corporation, because the legislation would impact the corporation’s future profits. As an example, Obama did the right thing in killing the Keystone pipeline, because he concluded that it would add to the crisis we’re facing from climate change. But the United States is now being sued for $15 billion by TransCanada, the owner of the pipeline, because NAFTA bars governments from taking actions that limit the profits of a multinational corporation. And the lawsuit doesn’t go to an American court. It goes to a three-person tribunal, which is made up of corporate lawyers.

Under these trade agreements, the president must accede to corporate profits. If a poor country wants cheap prescription drugs for malaria or for AIDS, and a corporation says you can’t use a generic product because we can make more money by keeping the brand name, then people will die in that country, and likely the tribunal will sustain that. This is a world of insanity, and it’s enshrined in the TPP.

We are coming up on the end of eight years under President Obama. What do you think was his single biggest achievement, and what was his single biggest failure?

There’s a criticism today that the economy is not where we want it to be; I make that criticism every day. But let’s not forget for one second, let’s never forget, where this country was when Obama came into office. We were losing 800,000 jobs a month. A month! We were running up a $1.4 trillion deficit, and the world’s financial system was fairly close to collapse. Other than that, things were pretty good when Bush left office. [Pause] That was a joke. In other words, the man came into office inheriting economic hardship, the worst since the Great Depression.

And two wars.

And two wars! And, on top of that, we had our Republican leaders meeting literally on the day of the inauguration and deciding that they would do everything they could to obstruct anything the guy wanted to do. That’s what he faced when he came in.

Now, you and I can acknowledge that this country is very, very far away from where we want it to be. But compared to where we were eight years ago, it is day and night. And to some degree, Obama’s intelligence and strength have made that happen. We are living in difficult times, but the stock market hasn’t collapsed, employment is not at 14 percent. So you ask me a major accomplishment? That’s a pretty good accomplishment.

On a personal level, I am always impressed by his discipline, his incredible focus, and his intelligence. When you are president of the United States and exposed to media 24 hours a day, it is so easy to say stupid things to get yourself in trouble. He has done that very, very rarely. No president I can recall has had the kind of discipline and focus that he has, and that is no small thing.

So what do you see as his biggest failure?

He ran in 2008 a brilliant campaign. One of the great campaigns in American history. He rallied the American people, he gave the American people hope. He put together, to some degree, the kind of Rainbow Coalition that Jesse Jackson had talked about. But what he did after becoming president was essentially to say, “Let me thank all the people who helped get me here, but I will take it from here. Mitch McConnell and I will sit down and work out the future.” He misunderstood that Republicans had no intention to negotiate anything. He severed his ties with the grassroots that got him elected, and you can’t take on the powers that be in this country—the power of the media, the power of Wall Street, the power of corporate America, the power of the drug companies—unless there is a mobilization of millions of people to demand fundamental change. Intellectually he understands that, but for whatever reason he did not implement that.

At the same moment that Obama shut down his grassroots machine, Republicans were creating one of their own. But as we’ve seen with the Tea Party, it’s easy for that kind of operation to become a Frankenstein monster. Part of the challenge of organizing the dispossessed is that the pent-up frustrations you tap into inevitably take on a life of their own. Do you think you can tap into that energy on the left and make it productive?

That’s a good question. Let me repeat: I think it is a very, very difficult task. I don’t say, “Hey, let’s snap our fingers and create a broad-based grassroots Democratic movement involving millions and millions of people.” It is a little bit easier to say than to do.

Somebody reminded me just the other day of something that happened during the Progressive era, during the early part of the century. The Progressives signed up 60,000 actual teachers to go out into communities and educate people about the issues of the day. Certainly social media and bright young people can play an enormous role in that effort today, in a way that we have never seen before. But the goal remains to educate and to organize. You are right in saying it is not easy, and no one can predict what the end result will look like. But it is absolutely imperative that we do that. Absolutely imperative.

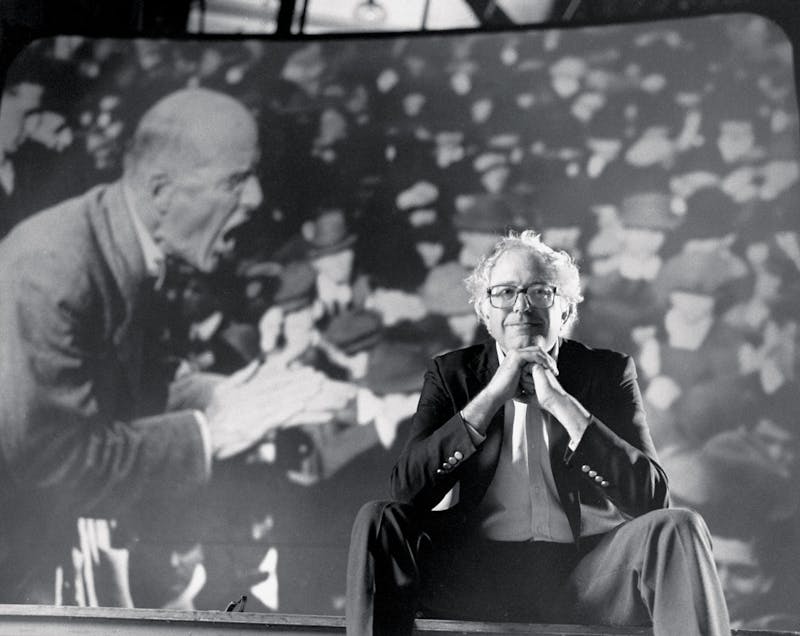

I can’t think of any presidential candidate, certainly in our lifetime, who has shared less about himself personally than you have. So let me ask you a personal question in the guise of politics. I know that Eugene Debs, the socialist organizer and presidential candidate, is a hero of yours. [Sanders smiles and points to a bronze plaque of Debs on the wall of his office.] When did you first come across him, and what effect did that have on you?

When I was in college, I began to read a lot about socialism, and obviously Debs was right in the middle of that. Extraordinary man—people of his period described him as a Christlike figure who would literally give you the shirt off his back. He had money in his pocket, he gave it away. He was a man who had the common touch, who was very close to the people, who had incredible courage, who stood up and opposed the hysteria of World War I, when the government wiped out the Socialist Party. He ran for president when he was in jail—did you know that?

It was in the 1920 election. He got a million votes while he was in jail.

If they counted all of his votes, which we have reason to believe they didn’t. So this is a man of great integrity and great courage, and if you read what he wrote—wow, it still reads brilliantly today. In the mid-1970s, I did a video on Debs. I did that because I spoke at the University of Vermont during that time and I asked, “Has anybody here heard of Eugene Debs?” Very few hands went up. It just struck me how sad it was that our young people have very little understanding about American history. I would have continued making films like that if I hadn’t been elected mayor of Burlington.

You’d be the Ken Burns of the left?

That’s right. Or what’s his name, who died recently. The one who wrote that book.

Yeah. I mean, it was just invaluable stuff, to take a look at American history in a way that most history books and PBS do not.

Other than Debs, is there someone in politics past or present who you particularly admire?

Yeah, I’ll tell you. The more I read, the more I was impressed with Martin Luther King Jr. Now everybody says, “Well, of course he was a great hero and he led the civil rights movement.” But what was extraordinary about this man was his incredible courage. The establishment said to him, “Congratulations, you got a Voting Rights Act and we’ve done away with segregation in the South—my God, what an unbelievable achievement. Now you can rest on your laurels.” But his conscience said, “You know what? I talk about nonviolence every day, and yet an incredibly violent and horrible war is taking place in Vietnam. And yes, that war is being supported by the guy who signed the Voting Rights Act, but I have to come out against it.” And then he said, “I get money for my organization from wealthy white liberals, but you know what? In this country we have an awful level of income and wealth distribution, and what does it matter if I integrate a restaurant when people can’t afford to eat at that restaurant? I am going to put together a Poor People’s March on Washington, even if the media does not pay any attention to me anymore, to demand a change in national priorities so we don’t give tax breaks to the rich, we don’t fight a war in Vietnam, but we pay attention to the needs of ordinary people.” Whoa! What incredible courage. That’s not what you are going to see on television, but that is the truth about the man’s life. He knew what he was doing.

It goes back to the question I asked you earlier. King went from looking at racism as an issue unto itself, to seeing it as part of a system of economic injustice. People forget that when he was assassinated, he was in Memphis to support a strike.

Exactly. He was there to deal with the garbage workers fighting for decent wages and working conditions. Which is of no interest to the media at all. So going back briefly to your question: Do you remember what the 1963 March on Washington was called? The full name of it? It was called the March for Jobs and Freedom. And “jobs” came first.

What King understood is, what good is it if you give people the right to go to Harvard University if you can’t come up with the $40,000 a year that it takes to attend? If you are sitting in a low-income community and youth employment is 50 percent, and your dad has no job and you have no money—that’s what matters. That it is not just a black issue, it’s also a white issue. One of the horrors in America today—and this is sad, but interesting—is that the life expectancy for working-class whites, especially women, is going down precipitously. That has a lot to do with despair: bad jobs, no jobs, turning to drugs, turning to alcohol, turning to suicide. So the ability of Trump to gain support among people by running a campaign based on bigotry has to do also with people hurting economically and needing someone to blame. The two things go together.

Any final message you want to share with your supporters, who themselves feel some despair that their choice is between Trump and Clinton?

I would ask people to take a look at history and to understand that change never, ever, ever comes about in a short period of time. To take a look at the struggles of the civil rights movement, of the women’s movement, of the union movement, of the gay movement, of the environmental movement, and to understand that all of those movements took years and years and are still in play today.

In the campaign, what we did is show the American people that the ideas the establishment had thought were fringe were really not fringe—that millions of people want to transform this country. It’s not gonna happen overnight. The fight has got to continue. And if you are serious about politics, then you gotta put your shoulder to the wheel and keep going. Sometimes the choices that are in front of you are not great choices, but you do the best you can. And the day after the election, you continue the effort.

Anyone who thinks that Hillary Clinton will not be more sympathetic, more open to the ideas we have advocated than Donald Trump obviously knows very little. So the day after the election, we begin the effort of making Clinton the most progressive president that she can become. And the way we do that is by rallying millions of people.

You ask me about my personal life. I’ve got seven beautiful grandchildren, and I want them to be able to grow up in a decent country. We all have the responsibility to work as hard as we can to make that happen—understanding, as has always been the case, that there are gonna be obstacles in the way. Look up what happened to Eugene Debs. He spent his life working to build a socialist movement, only to see it destroyed. Then ten years later, FDR picked up half of what Debs was talking about.

That’s how the world works. We don’t have the luxury to give up, OK?

Thank you for taking the time to talk.

Thank you very much. [Turns to his aide.]

Well, Josh—any crises that we face? No? Well, you know where to reach me.