In early July, Ruth Bader Ginsburg did something apparently unprecedented for a Supreme Court justice: She trashed a presidential candidate in the midst of an election. If Donald Trump won the presidency, she warned, “everything is up for grabs.” A few days later, she elaborated, “I can’t imagine what the country would be with Donald Trump as our president. . . . For the court . . . I don’t even want to contemplate that.” If her husband were still alive, he would have viewed a Trump victory as “time for us to move to New Zealand.” And the next week, she doubled down: “He is a faker. . . . He says whatever comes into his head at the moment. . . . How has he gotten away with not turning over his tax returns?”

Trump, of course, can’t handle criticism from a woman, especially an old and powerful one. Predictably, he tweeted “her mind is shot” and told her to resign. But then, in a stinging editorial rebuke, The New York Times declared that Trump was right and that Ginsburg should “drop the political punditry and the name-calling.” One of her loyal former law clerks sadly admitted that Ginsburg had “stepped over the line.” A few commentators defended her—judges such as Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito have crossed it, too, after all—but most thought she had acted unwisely. Ginsburg released a statement regretting her remarks and promising to be more “circumspect” in the future.

Both attack and apology were out of character. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was born cautious. She is the essence of circumspection. She puts the prudence in jurisprudence. So why did she step over the line? Mark Joseph Stern at Slate speculated that Ginsburg had recklessly decided to “cash in her political capital after years of holding her fire.” As Ginsburg would say, I have to concur. But I was secretly delighted to see that the Practically Perfect Justice had committed a judicial crime of passion. Ginsburg is in a unique position of authority as probably the best-known and most admired living Supreme Court justice. Yet her office forbids her to speak out on political issues, and her authority as an impartial judge is undermined if she exerts influence outside the court. Barred from activism, she has instead come to represent an ideal, and the fact that she is a woman complicates that position even more.

Indeed, the terms applied to Ginsburg since her appointment to the court are a veritable glossary of ladylike propriety. She’s been repeatedly described as austere, deliberative, soft-spoken, schoolmarmish, solemn, modest, and reserved. Her own children decided that her “sense of humor needed improvement” and kept a book called “Mommy Laughed” to record the apparently rare occasions when they succeeded in provoking a chuckle. Now 83, Ginsburg still works out twice a week with a personal trainer, lifting weights, doing push-ups, planks, and squats, and tossing a twelve-pound medicine ball. She never misses a deadline and needs very little sleep. In fact, she often stays up all night writing her opinions and briefs, pausing only to indulge in her favorite snack: prunes. She is a guilt-inducing role model for senior citizens.

But since 2013, Ginsburg has been rebranded by a fan base that sees her as feisty, funny, and up-to-date. The phenomenon started when she issued her fierce dissent from the court’s 5–4 decision to kill the Voting Rights Act. Two young digital strategists in Washington wanted to pay tribute, and distributed stickers with an embellished painting of Ginsburg, in her black robes and big glasses, with a sketched-in white crown and the slogan “Can’t Spell Truth Without Ruth.” They also put it on Instagram. In New York, a young law student, Shana Knizhnik, posted the image on Tumblr with the title “Notorious RBG,” playing on the contrast between the pugnacious 300-pound rapper Biggie Smalls, who died in an unsolved drive-by shooting on the streets of L.A. at the age of 24, and the judicious Jewish grandmother who has spent much of her life on the mean streets of the Upper East Side.

The term “notorious” was the attention-grabbing antithesis of every sexist and ageist stereotype that Ginsburg was burdened with. By 2015, Ginsburg had become an icon for a new feminist generation with her own tchotchkes—T-shirts, mugs, and key-chains. Was it the secret superhero Notorious RBG who blasted Trump, or was it the indomitable Justice Ginsburg, finally breaking free of her chains? Are the young right to idolize her as someone who rejects outmoded rules and pursues her own course, or has she earned her present stature by excelling in the traditional path to the top? And should she stay on that path or blaze a new one?

Ginsburg is now the subject of two excellent books that reconcile the two Ruths, by telling the story of her inspiring life and her towering career. My Own Words, skillfully edited by two Georgetown law professors, Mary Hartnett and Wendy Williams, brings together Ginsburg’s writings—briefs, articles, speeches, lectures, and bench announcements—over 70 years, from the age of 13 to 83. The selection showcases her astonishing intellectual range, from law and lawyers in opera, to tributes to Louis Brandeis, William Rehnquist, and Gloria Steinem, to the significance and form of dissenting opinions. The book also includes a number of revealing speeches Ginsburg has given about her historical heroines, starting with Belva Lockwood, who went all the way to President Ulysses S. Grant to demand her law degree, and at the age of 75 became the first woman to plead before the Supreme Court. Lockwood’s message to women was: “We shall never have equal rights until we take them, or equal respect until we command it.” Hartnett and Williams’s brief biographical introductions to each section show how much Ginsburg has heeded it.

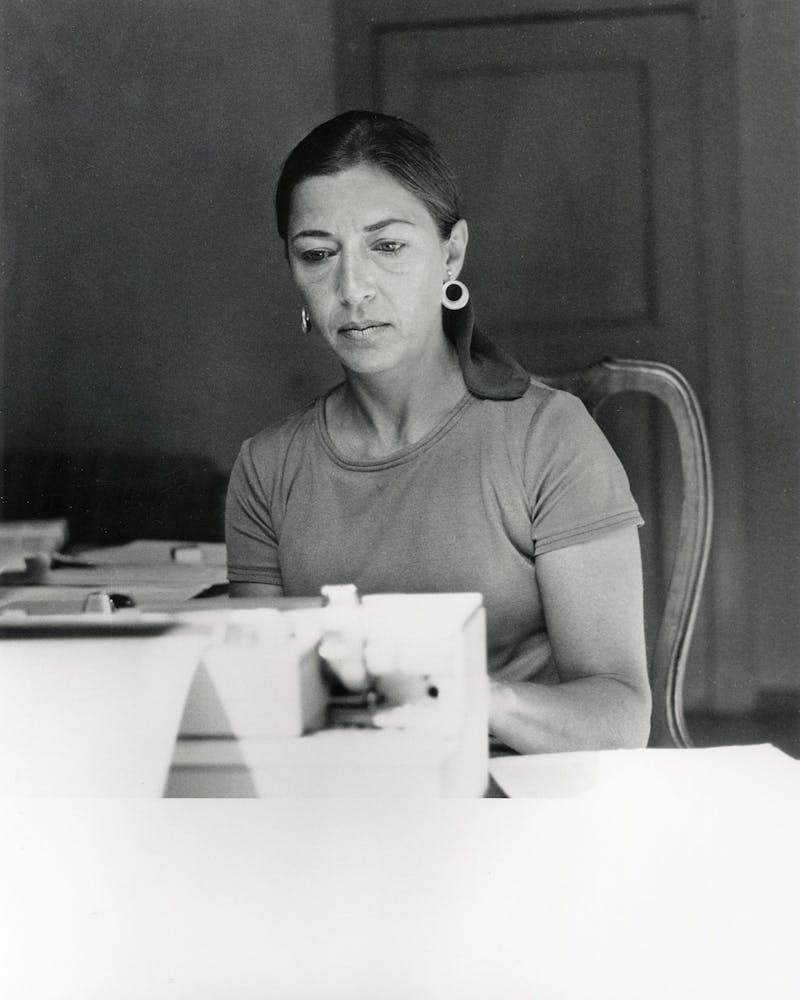

The best-selling Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, by Knizhnik and journalist Irin Carmon, focuses on Ginsburg’s evolving image and cultural currency. It reproduces many black-and-white photographs of a stylish and vivacious Ginsburg. (My Own Words includes most of these, too.) As a senior at Cornell in 1954, she resembled a sultry Lizabeth Scott or a glamorous Veronica Lake. As late as 1980, she was elegantly tailored, smiling, and chic in her roles as lawyer, professor, and ACLU strategist. Not until 1984, at the age of 51, was she photographed tight-lipped and forbidding in the black robe of a federal appeals court judge. The judicial robe is intended to mask difference between the judges, and Ginsburg has welcomed it as a symbol of unity: “We are all in the business of impartial judging.” But the robes were never meant for women. Ginsburg and Sandra Day O’Connor adopted a wardrobe of frilly and jeweled collars to mark their difference, but even the lacy jabots make her look like the nineteenth-century suffragists whose lacy caps suggested unthreatening femininity when they spoke in public.

Notorious RBG includes many full-color photographs of Ginsburg in all her private roles—posing with her husband in her judicial robes while he is wearing an apron; in India in a turban, riding on an elephant behind her friend Scalia; whitewater rafting with colleagues in Colorado; and, most spectacularly, as a radiant extra in the opera Ariadne auf Naxos at the Kennedy Center, holding a lovely fan, wearing a white ball gown and a flattering platinum wig. Carmon and Knizhnik also display her status as a cultural icon in sketches by court artists, cartoons, portraits, tattoos, nail art, embroidery, greeting cards, Halloween costumes, and fan selfies. Her willingness to be seen and photographed in playful public appearances marks her as one of the most approachably human justices in recent memory. And by bringing her image into popular culture, Carmon and Knizhnik override some of the generational conflicts in feminism that exclude older women from the community.

The chapter titles (“Been in This Game for Years”) are taken from the lyrics of Notorious B.I.G., with subtitles like “RBG’s Swag.” But the book is also thoroughly researched through archives and interviews. The authors are both lively and serious in their attention to Ginsburg’s legal career, providing accessible introductions to her major opinions and dissents, helpfully reprinted with key passages highlighted in boldface, and annotated in red by two law professors. For those to whom RBG’s cultural appeal is obvious, there is an exploration of her legal importance, and vice versa. Perhaps more than anything else, the book demonstrates that to understand her formidable influence, you need to understand both.

Ginsburg grew up in Brooklyn as a remarkably intelligent, reflective, and socially conscious child. Her first published article—printed in her elementary school newspaper, Highway Herald, in 1946—urges her eighth-grade classmates to emulate the charter of the United Nations and “try to train ourselves and those about us to live together with one another as good neighbors.… It is the only way to secure the world against future wars and maintain an everlasting peace.” As a teenager dealing with her mother’s death from cervical cancer, she kept her worry and sorrow private, graduating near the top of her high school class, playing cello in the orchestra, twirling a baton as a cheerleader at football games. She was, a classmate recalled, “beautiful, outgoing, and friendly.” At Cornell on a scholarship, she joined a sorority, majored in government, studied European literature with Nabokov, and read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.

She also encountered McCarthyism at Cornell, when one of her professors was punished for defending freedom of speech, and she was drawn to the law as a weapon against such abuses. The most important event of these years, however, and the turning point of her life, was meeting and marrying the gregarious, generous, and adoring Martin Ginsburg in 1954. In the preface to My Own Words she confesses, “I do not have words to describe my supersmart, exuberant, ever-loving spouse.” He is the co-star of her biography. The egalitarian life partnership they created together was highly unusual in the 1950s. They supported each other’s careers in the law, took turns moving for good jobs, shared child care and parenting, nursed each other through cancer, and loved opera, golf, and travel.

An easygoing, popular extrovert, Martin dragged Ginsburg away from her desk and drew her into social life. Having taught himself to cook from Escoffier, he took over the family meals and entertaining, hosting an annual New Year’s feast, to which Scalia would bring “the spoils of a recent hunting trip.” One guest joked that “Scalia kills it and Marty cooks it.” Along with John O’Connor, he enjoyed being a member of the “Dennis Thatcher Society” of First Gentlemen.

Above all, he gave her the gift of confidence. “He always made me feel like I was better than I thought myself,” Ginsburg has said. “I started out by being very unsure. Could I do this brief? Could I make this oral argument?” For decades, she’d had to quietly accept second-class professional status. At Harvard Law School, she was shut out of the men-only Lamont Library. In order to follow her husband to a job in New York, she transferred to Columbia Law School, graduated top of her class, and served as editor on the prestigious Law Review, only to struggle to find a job herself.

In 1963, she was the second woman hired at Rutgers School of Law–Newark. Still, the dean told her “it was only fair to pay me modestly because my husband had a very good job.” She didn’t protest for herself, although she filed successful suits in behalf of her women faculty colleagues, and taught one of the first courses on sex discrimination and the law. During her career, she recalls trying to hide her pregnancy from her bosses; going into club dining rooms through the back door; looking for a women’s bathroom in various offices; toughing out sickness and surgery so as not to seem weak. But in her marriage, she said, “I didn’t get second-class treatment.”

Marty’s support helped Ginsburg to find her forceful public voice. She has said that if she could have chosen any profession, she would like to “have had a glorious voice” and be a “great diva.” But speaking in court, she was initially “shy,” a code word for feminine self-doubt. She made up for it by knowing all the facts. When she argued her first case before the Supreme Court in 1973, Justice Harry Blackmun graded her C+ for eloquence in his little notebook, adding “very precise female.” Her women students at Rutgers also described her speaking “flatly, sometimes haltingly, but always precisely.” She speaks so slowly and with such long pauses that one of her clerks noticed how “there was always a point where you thought you were at the end of the conversation, where you weren’t sure if she was fully done.” Marty said she was the same at dinner.

Her breakthrough from procedural cases to gender discrimination law also came through her partnership with Marty. In 1970, through his practice as a tax lawyer, he discovered the case of Charles E. Moritz. Moritz, who acted as caregiver for his mother, wanted to claim a $600 dependent-care tax deduction, but because he was an unmarried man, he was deemed ineligible. “If I were a dutiful daughter instead of a dutiful son,” he protested, “I would’ve received the deduction.” Marty showed the case to Ruth and persuaded her to sign on pro bono. With the backing of the ACLU, the Ginsburgs took it as a team to the Tenth Circuit Court, which allowed Moritz to take the deduction.

Since then, a few major themes have united Ginsburg’s many cases and opinions about gender equality under the law. She’s been guided by the principle of equal protection for women to become full citizens. In United States v. Virginia Military Institute (1996), she argued that a law or official policy must be challenged and changed when it “denies to women, simply because they are women … equal opportunity to aspire, achieve, participate in, and contribute to society based on their individual talents and capacities.” She has consistently opposed “benign” legislation that prevents women making their own choices and decisions, on the basis of sexist assumptions about their wishes and needs. She also has defended affirmative action. When she got tenure at Columbia Law School, some of her colleagues gossiped maliciously that she was only promoted because of pressure to hire a woman. “At least,” she wrote drily, “the days of ‘negative action’ were over.”

On these principles, she insists that pregnancy is a temporary disability and that women should not be penalized or restricted during or after it, holding that “presumably well-meaning exaltation of woman’s unique role in bearing children has, in effect, denied women equal opportunity to develop their individual talents and capacities, and has impelled them to accept a dependent, subordinate status in society.” She has been ahead of her time in seeing that laws limiting the employment of pregnant women reflect patriarchal horror of female sexuality: “Only a woman’s body showed proof of having sex, and only women were punished for it.”

Educating the courts to understand these principles has been a project of many years’ duration. In 2003, she opposed the Supreme Court’s assent to the ban on so-called “partial abortion.” When the ban was upheld in 2007, she argued in her dissent that “the court shields women by denying them any choice in the matter. This way of protecting women recalls ancient notions about women’s place in society and under the Constitution—ideas that have long since been discredited.” Not discredited by everyone, alas. Ginsburg has long maintained that legal change would follow and reflect social changes, and that judges were affected by “the climate of the era.” The court would evolve with the culture, not lead it. But what if the court is packed with judges opposed to social change?

In the tradition of the American judicial system, Ginsburg has scrupulously avoided confronting her colleagues and making disagreements personal. In her written pronouncements as well as her oral arguments, she has always stressed the importance of clarity, collegiality, and civility. “I prefer and continue to aim for opinions that both get it right, and keep it tight,” she has written, “without undue digressions or declarations or distracting denunciations of colleagues who hold different views.” Indeed, she has bitten her tongue and censored her language to avoid criticizing her fellow judges. In 1993, she insisted that “one must be sensitive to the sensibilities and mindset of one’s colleagues, which may mean avoiding certain arguments and authorities, even certain words.” She strategically avoids open conflict by often concluding a talk or brief with a quotation from an unimpeachable judicial authority, usually a dead male, in place of her own opinion, and adding something like, “I heartily concur in that counsel.”

She is also careful not to identify by name men whose opinions are so outrageous or stupid that she cites them as ridiculous examples. In one lecture about the uses of international law, for instance, she quotes a number of obtuse senators interrogating Elena Kagan at the hearing on her nomination. “One asked whether judges should ever look to foreign laws for good ideas.” Who is this idiot? She gives no footnote.

But there are a few exceptions. In 1993, just before her appointment to the Supreme Court, Ginsburg reiterated her belief in good manners and mutual respect, quoting the distinguished legal scholar Roscoe Pound’s recommendation that the opinions of an appellate judge should exclude “intemperate denunciation of colleagues, violent invective, attributions of bad motives to the majority of the court, and insinuation of incompetence, negligence, prejudice, or obtuseness.” She then gave some examples of judges attacking the opinions of their opponent as ludicrous, outrageous, or inexplicable. There are footnotes for these examples, and several come from Scalia. Once she got to the Supreme Court, however, she was much more careful not to offend him.

Yet this ladylike and restrained stance has slowly changed as Ginsburg has grown impatient with the glacial pace of judicial progress and the renewed efforts to reverse equal-rights decisions. Her radicalization may have started in 2005, when Sandra Day O’Connor retired. As Slate journalist Dahlia Lithwick has observed, Ginsburg “hated being the only woman” on the court. (Sonia Sotomayor would not be appointed until 2009, followed by Justice Kagan a year later.) She found herself in the unwelcome position of speaking for all women, and her fellow justices, all male, began issuing opinions that reversed the progress she had spent much of her life working for. She soon started writing tougher dissents. In The New York Times, Linda Greenhouse speculated that Ginsburg “may have concluded that quiet collegiality has proved futile and that her new colleagues . . . are not open to persuasion on the issues that matter most to her.” It might be more effective to appeal directly to the public.

By 2007, Ginsburg was speaking out. She read aloud forceful oral dissents from the decisions upholding the federal Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act and denying Lily Ledbetter’s suit against Goodyear Tire and Rubber over unequal pay. She openly confronted disagreements in the court, such as Alito’s responsibility for the outcome in the abortion case. Her friend the sociologist Cynthia Fuchs Epstein has commented that Ginsburg had “always been very ameliorative, very conscious of etiquette. She has always been regarded as sort of a white-glove person, and she’s achieved a lot that way. Now she is seeing that basic issues she’s fought so hard for are in jeopardy, and she is less bound by what have been the conventions of the court.” A photograph in My Own Words shows Ginsburg vigorously working out in a sweatshirt that says super diva. She was finally taking off her gloves.

The next big change came with Marty’s death in 2010. His heartbreaking farewell note to her is reproduced in both books: “I have admired and loved you almost since the very day we first met.” On her own, Ginsburg was forced to take charge of her social life. Her friends have found her more engaged in conversations outside the law, and she seems to have assumed for herself the sense of confidence and the right to be heard that Marty had patiently supported. Finally, with the unexpected death of Scalia in February, and the Republican Party blockade of his replacement, the tradition of collegiality on the court was demolished.

Today, the Supreme Court is not just part of the political agenda; for Republicans, it is the agenda. Ginsburg’s seat will be at the center of a fight if, as many expect her to, she chooses to retire in the next few years. For the time being, as Rob Hunter argues in his provocative review of Notorious RBG in Jacobin, Ginsburg’s dissents, however stirring, reflect losses not victories; they are “an index of powerlessness.” Without political clout, high moral considerations and restraint are a luxury.

It is possible Ginsburg could actually be more influential outside the court, where she could speak freely, than by remaining on the bench. Her decision to stay on is a risky gamble. She has said that she will step down when she can’t do the job and maintain the pace—when she can’t remember the “names of cases I once could recite at the drop of a hat.” Meanwhile, she’s already hired the four clerks who will work for her through 2018. If Trump wins, we’ll have to pray that she can hang on long enough to prevent him from stacking the court for the rest of the century with young conservative ideologues. If Hillary Clinton wins, Ginsburg may want to stay on because, as the senior judge on a court with a liberal majority, she would have a unique opportunity to further her views of justice and the Constitution.

Ginsburg, of course, has the right to stay on and continue to make the judgments that will complete her life’s work; moreover, much of the current clamor for her retirement is fueled by sexism. But there’s another way for her to use her moral authority and exert her political power. Now that she has found her voice, she will surely want to keep on writing and speaking out to the public. It will be up to her to decide whether she can do it more effectively on the court or off it. As a private citizen, she could say whatever she damn well pleases. Beyond the antitheses of the austere Justice Ginsburg and the Notorious RBG is the woman she has always dreamed of being, speaking her own words in a grand and powerful voice: the Glorious RBG.