Since his death in a car accident on January 4, 1960, Albert Camus has led a kind of double-afterlife. In the West, he is not only remembered as one of the great writers of the post-war era, but as a hero of the resistance, a celebrity intellectual, and a style icon—“the Don Draper of existentialism,” as The New Yorker once put it. His best-known book, The Stranger, is a staple of high school curricula and virtual rite of passage for adolescents who may see something of themselves in Meursault, that avatar of sullen rebellion. But in Algeria, where he was born and raised—and in former European colonies in general—Camus cuts a different figure. At best, he is a compromised genius; at worst, an oppressor whose lionization has extended the colonial perspective well into the twenty-first century.

These two versions of Camus, like a superhero and his all-too-human alter ego, are rarely seen at the same time. Earlier this year, Camus was celebrated in a month-long retrospective in New York, commemorating his first visit to the United States. By the time of that trip, in 1946, all the components of Camus’s legend were in place. As the former editor of the underground newspaper Combat, he embodied the humanist response to Nazism. As an associate of Jean-Paul Sartre and the existentialists, he represented the new philosophical thinking emerging from the rubble of Europe. And, as a magnetic and sought-after public figure, he was seen as a man who, after years of war and unprecedented horror, could lead others to believe in life again.

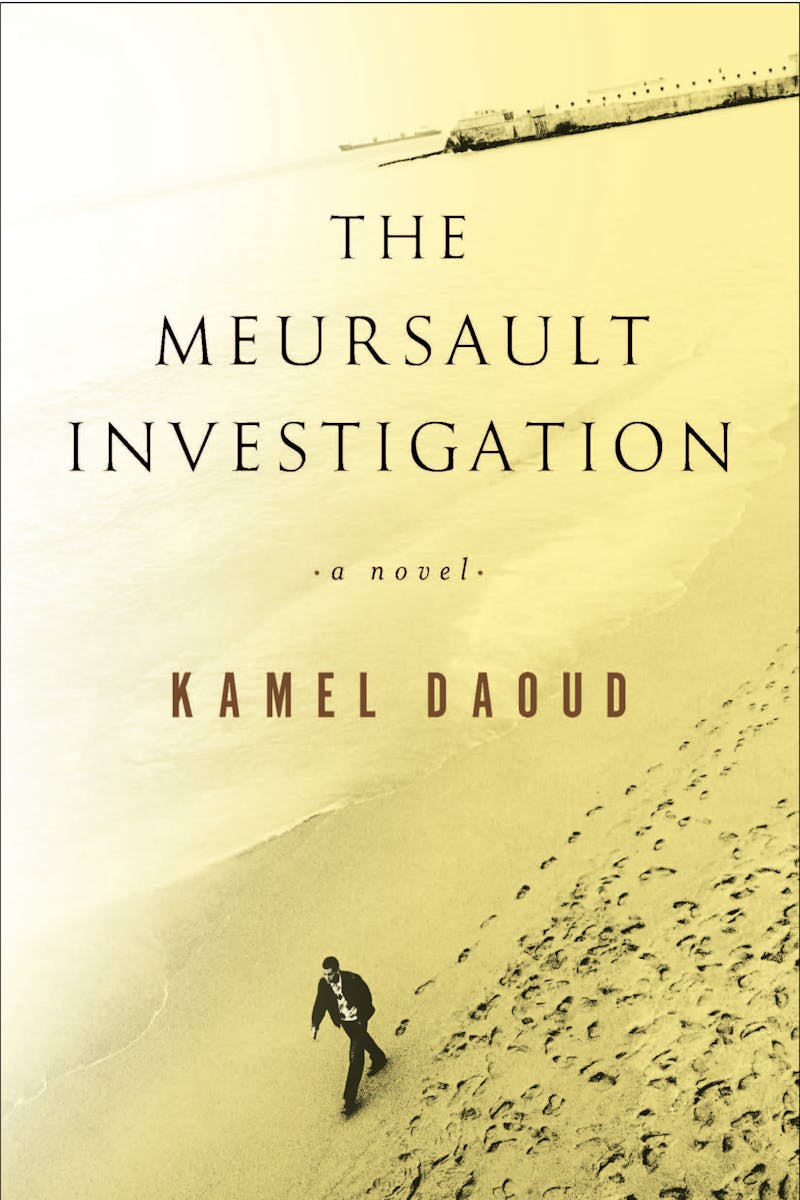

But in the months before the retrospective, the Camus legend looked shakier than ever. The English-language publication of the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation in the summer of 2015 occasioned a wholesale reassessment of Camus’s reputation in the mainstream press. Daoud’s novel, which is told from the perspective of the brother of the nameless Arab that Meursault kills in The Stranger, became an instant classic of post-colonial literature, rendering vividly Camus’s blind spots and latent biases. The Moroccan-American novelist Laila Lalami suggested that whereas The Stranger had erased Algerians, Daoud made the country “more than just a setting for existential questions posed by a French novelist.” The Guardian reported that Daoud’s novel had revived criticisms of Camus’s “inability to see violence through a non-white, non-colonial prism.”

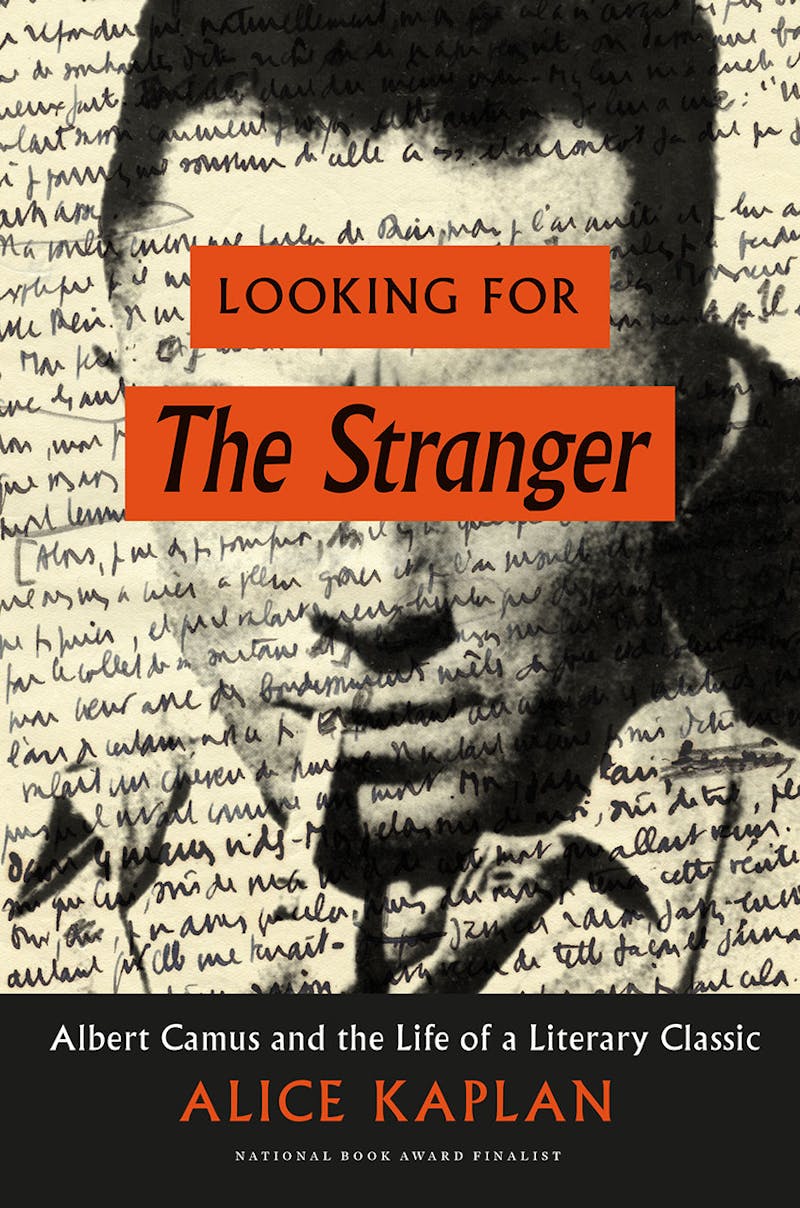

Camus’s complex relationship with Algeria is one of the central themes of Alice Kaplan’s new book, Looking for “The Stranger,” which attempts to reconcile Camus’s dueling legacies. It is a historical account of how Camus’s novel came into being, starting with the famous opening sentence—“Today, Maman died”—scrawled in a notebook marked “22” in the fall of 1938 in Algiers. But, like the characters in Daoud’s book, Kaplan is also conducting an investigation. She searches for the creative origins of The Stranger in the strained relationship between Arabs and Europeans in Algiers’s lower-class neighborhoods of Belcourt, where Camus grew up, and Bab-el-Oued. And as her investigation deepens, she is drawn into the real-life story behind the unnamed Arab who, like Camus’s shadow, lives on as a silent rebuke to his creator.

The post-colonial critique of The Stranger has a long history. Lalami’s criticism echoes Edward Said’s assertion, in 1989, that the Arabs in The Stranger “are nameless beings used as background for the portentous metaphysics explored by Camus.” (Said, in turn, was echoing Chinua Achebe’s 1975 critique of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: “Can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing Africa to the role of props for the breakup of one petty European mind?”) Said’s essay was a cornerstone of post-colonial theory, whose influence in academia has changed the way we see scores of writers, from Conrad to Graham Greene to E.M. Forster. But doubts about Camus went back still further, and were rooted in his politics. Camus had opposed Algeria’s war for independence from French rule in the 1950s and ‘60s, and had instead proposed an Algerian federation in which Europeans, Arabs, and other groups lived in harmony. (Neither Arab freedom fighters nor French settlers liked this plan.) The French historian Pierre Nora wrote as early as 1961: “Meursault, in killing the Arab, represented the unconscious wish of the French in Algeria—keep the land and destroy the enemy.”

But what separates Camus from a Conrad or a Forster is that Algeria was undoubtedly a part of him. The Stranger is steeped in its burning light—“like a sun in a box,” as Daoud describes it—and shrouded in its desert silence. As an adult, he never felt quite at home in the wealthier enclaves of Algiers, let alone in cold, gray Paris, because they deprived him of what he “loved most in Algiers,” Kaplan writes, “the smell of the ocean and a view of the bay on nearly every street corner.” He was of Spanish and French descent, but his family had been in Algeria for generations, and Europe was so foreign to them as to be unimaginable. As Camus wrote in The First Man, his autobiographical bildungsroman, France was for his beloved mother “an obscure place lost in a dim night which one reached through a port named Marseilles, which she pictured like the port of Algiers.”

And they were very poor. Unlike other pieds noirs, they lived close not only to the Arabs of Algiers, but also to Spaniards, Jews, and Berbers. Camus’s unlikely rise out of poverty—in The First Man, he pays tribute to the teacher who put him on a path toward a scholarship at the lycée—connected him all the more deeply to the plight of those suffering under French rule. When he was in his twenties, Camus earned a living as a journalist. In 1939 he reported on how the Kabyles, an ethnic group in the Tell Atlas mountains, were starving to death because of French neglect and discrimination. He covered the courts in Algiers, where he saw how the rule of law was twisted to protect Europeans at the expense of Arabs. The absurdities of the justice system went straight into the court scenes in The Stranger, while the squabbling violence he saw between Europeans and Arabs partly inspired the book’s main plot device and thematic hinge: the killing of an Arab.

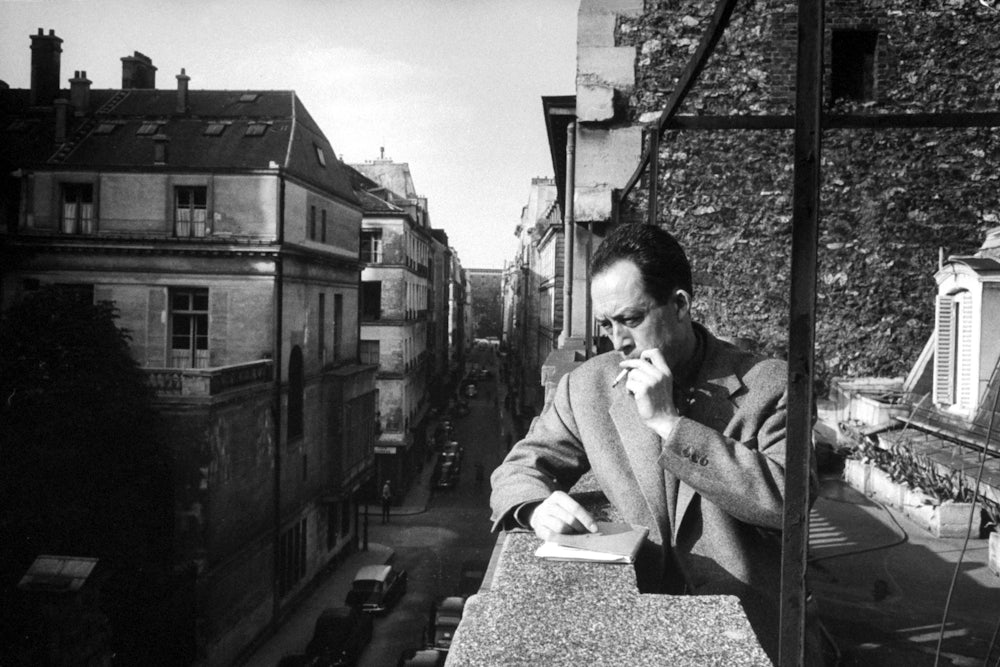

All of this served to harden Camus’s long-held conviction that the French administration would be doomed without top-to-bottom reform. For his efforts, the anti-colonialist newspaper he wrote for, the Alger-Républicain, and its successor were shut down by the colonial authorities, and he was blacklisted, forcing his eventual exile in Paris. It was there, in a hotel room in Montmartre, that Camus completed a first draft of The Stranger in May 1940. Even though he had a day job as a newspaperman, he would return to his manuscript “and pick up exactly where he had left off, with no difficulty,” Kaplan writes. As Camus wrote to his wife Francine: “I’ve been carrying it with me for two years and I could see by the way I wrote it that it was already completely traced within me.”

It is hard, however, to see any trace of Camus in the story he transcribed on the page; it is more like a “photographic negative,” as he would later write in his journal. It begins with the death of Meursault’s mother, to which the character shows a troubling indifference. Meursault proceeds to live a carefree, aimless existence in Algiers, wanting nothing more than to satisfy his most immediate desires: going for a swim, having a smoke, making love. He falls in with a pimp, almost out of sheer passivity, and becomes embroiled in the pimp’s dispute with his girlfriend—a “Moor,” i.e. an Arab, who also goes unnamed. The dispute expands to include two Arab men, one of whom Meursault shoots dead on the beach. He then is put on trial, not for killing the Arab, but for being a heartless son who never loved his mother. All of this stands in polar contrast to the author, who was a doting son, a driven young adult, and an activist who loathed, and campaigned against, colonial violence.

This inversion of his sympathies, this upside-down world, would seem to belie the notion that the depiction of the Arabs in The Stranger reveals Camus’s true feelings toward Arabs—that they are incidental, less than human. In fact, Kaplan shows that Camus’s treatment of the Arabs was very deliberate. In the fall of 1938, he sketched out the story of the Moorish mistress, the first discernible scene from The Stranger to appear in his notebooks. By the spring and summer of 1939, he knew that his main character would kill an Arab. The relationship between Europeans and Arabs is, as Kaplan writes, the “backbone” of the book, not merely a platform to pontificate about the absurdity of life. Furthermore, she argues, convincingly, that his use of appellations like “Arab” and “Moorish” are not evidence of unconscious prejudice. Rather, “by reducing a man to his ethnic label,” they are meant to convey a wider prejudice prevalent in colonial Algeria—an inability to see the Arabs as people.

At one point in The Meursault Investigation, the main character, Harun, describes a scene that is fixed in his mind: the beach ablaze under the merciless Algerian sun, and the ghostly outline of his brother, Musa, prone on the sand. Above him there is “a man holding a cigarette or a revolver”—one of the many instances in which Daoud conflates the character Meursault with Camus, who was often photographed with a smoldering Gauloises between his lips. “The scene never changes,” Harun says, “and I beat against it like a fly against the windowpane.” The scene produces in him a welter of feelings—curiosity and excitement, but also anger and sadness—as well as an impossible desire “to pass through the screen or follow the white rabbit.”

This passage is a good representation of Daoud’s style: densely allusive, rich with simile, emotionally naked. If Camus’s prose, influenced by hardboiled American detective novels, is as cool and polished as the barrel of a gun, then Daoud’s is raw, jagged, confessional. (It is, in fact, an homage to Camus’s novel The Fall, adding yet another thread to Daoud’s dizzying intertextual tapestry.) The passage captures the utter frustration of the Arab reader of The Stranger, the inability to break the scene open and dive into the life of the anonymous Arab who is eternally nothing more than a blank, a void. Daoud voices that frustration, and answers it by coloring in the details of the murdered man’s life, and giving him a name, Musa, that sounds a lot like Meursault.

By expanding the universe of The Stranger, Daoud gives us not only a necessary Arab perspective on the relationship that so haunted Camus, but a new understanding of what Camus was trying to achieve in that enigmatic scene on the beach. The Meursault Investigation is, without a doubt, a critique of The Stranger, but it is also much more: an interpretation, a sympathetic companion, one pole of a shared world.

This mirroring is most obviously evident in Daoud’s postmodern plot, the centerpiece of which involves Harun shooting a French settler—a roumi—in revenge for Musa’s death. This act quickly becomes absurd: Harun is imprisoned by the mujahideen who are in the midst of liberating Algeria, not for killing the roumi per se, but for doing it during a cease-fire. Harun ends up a stranger in his own country, caught between the old order that fractured his family and a new order that has rejected him. If the novel is partly about the legacy of colonial violence—how it traumatizes its victims, and begets more violence—it is also about a painful estrangement from the world that succeeded it.

What Camus and Daoud share, then, is a deep ambivalence toward their homeland. While Camus loved Algeria like a family member, his exile forced him to acknowledge that it was not his completely. “I am not from here,” he wrote in his lonely hotel room in Montmartre, “not from anywhere else either.” He added, “A Stranger, who can know what this word means.” Before The Meursault Investigation, Daoud was best known for his polemical columns in Algeria’s Quotidien d’Oran, a French-language newspaper, where he launched attacks on Islamism, autocracy, and Arab nationalism—in other words, the very forces that took hold of Algeria in the post-colonial era. (He has since become something of an international spokesperson on these issues, extending his polarizing political reputation to Europe and beyond.)

These criticisms are everywhere in The Meursault Investigation, flowing like acid through Daoud’s embittered mouthpiece, Harun. On institutionalized Islam: “As far as I’m concerned, religion is public transportation I never use. This God—I like traveling in his direction, on foot if necessary, but I don’t want to take an organized trip.” On pan-Arab identity: “Tell me, is that a nationality, ‘Arab’? And where’s this country everybody claims to carry in their hearts, in their vitals, but which doesn’t exist anywhere?” On the malignant forces unleashed by the revolution, which led to a civil war between Islamists and Algeria’s ruling elite—le pouvoir, “the power”—in the 1990s: “[T]he beast fattened on seven years of war had become voracious and refused to go back underground.”

And so through various phases of disillusionment, Harun begins to identify with none other than Meursault. The Stranger, he says, is a “mirror held up to my soul and to what would become of me in this country, between Allah and ennui.” He understands, better than anyone else, how Meursault could commit such a heinous crime: “The murder he committed seems like the act of a disappointed lover unable to possess the land he loves.” That Daoud’s novel would end up on the side of the murdering pied noir has rankled some of his countrymen, one of whom characterized Daoud as a “self-hating” Algerian who “writes as if imperialism and capitalism didn’t exist” and who “comforts white readers.” This seeming betrayal could be read as Daoud’s way of playing Camus’s rebel, rejecting the community and all its trappings in the name of an uncompromising individual truth. But it is also to convey a broader truth of how we understand ourselves—through the other, the stranger, who is also us.

There’s a beach in the Algerian port city of Oran known as la plage de l’étranger—the stranger’s beach. Camus’s biographers have identified it as a spot where an altercation took place, between two Arabs and three of Camus’s friends, that very well may have been the real-life inspiration for the climactic scene between the Arabs and pieds noirs in The Stranger. The beach was off-limits to Arabs, setting off a scuffle between the two groups. A knife was brandished, resulting in an injury to one of the Europeans. They retreated to dress his wounds, before returning to the beach with a pistol. But in this version, no shot was fired. The knife-wielding Arab was arrested, but Camus’s friends didn’t pursue charges.

In a sense, the mystery of the Arab’s identity has been in plain sight for many years. Out of curiosity, and perhaps with an aim to right the scales of literary history, Kaplan decides to research this incident during a visit to Oran, where Camus spent time in his young adulthood before shipping off to France. Lo and behold, she finds the Arab, in a brief story about the seaside confrontation in the Alger-Républicain from 1939: a young man named Kaddour Touil. She finds his surviving family, and fills out his story. Like Camus, he was in France during the war, though he ended up returning to Algeria after marrying a Frenchwoman. No one remembers the fight on the beach—it is chalked up to boys being boys, “two young roosters on the beach.”

It is a fitting conclusion for a book that tries to square Camus’s warring legacies. But any lasting reconciliation has to occur when we actually read and interpret the book—on the very same beach, so to speak, where the Arab was killed. As Harun warns his unidentified interlocutor, “Don’t do any geographical searching,” since “[t]his story takes place somewhere in someone’s head, in mine and in yours and in the heads of people like you. In a sort of beyond.” In striking out for the beyond, Daoud manages to meet Camus at the point where he could go no further. In making his post-colonial critique, Daoud also offers its response.

Whether others will be as forgiving is another question. As Kaplan notes in her introduction to Algerian Chronicles, a collection of Camus’s reportage and essays on Algeria, his reputation has shifted with Algeria’s politics, particularly in the aftermath of the Islamist insurgency of the 1990s, when secular Algerians began to see something of themselves in the pieds noirs of the 1950s and ‘60s, who were deemed insufficiently Algerian. “What, we’re supposed to leave Algeria now?” one academic asks her. “We’re as much Algerians as they are!”

This was Camus’s own point about the pieds noirs, particularly the poor ones, like the members of his family, who knew no other home. Whatever the claims of justice or history, how could Camus deny what his own experience told him? This was the philosophy behind his most infamous statement about the war for independence: “People are now planting bombs in the tramways of Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, then I prefer my mother.” It read as solipsism then, but now it points to the primary quality that Camus and Daoud share: an aversion to fundamentalism of any kind. They attest that ideologies and scholarly theories have their limits, and that life is understood as it is lived. As the existentialists might say, there is only the world.