It’s not easy to become a woman anywhere. The years-long passage between what, if you’re lucky, is the bold and relatively invulnerable era of girlhood, and (again, if you’re lucky) the self-possession and confidence of adulthood, is fraught. And while so many recent books have taken on the subject of “girlhood” and troubled girlhood—Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, Girl in the Dark—they play up the drama of transformation more often than they address the ordeal of finding oneself in a suddenly altered reality, one that makes bodies objects of appraisal and potential violation and where there’s a confounding mix of new threats and desires, power and concessions.

When Blair Braverman enrolled at age 18 in a Norwegian “folk school”—a self-guided education program with the “distinctly Scandinavian” aim of fostering “uncomfortable self-awareness”—she wanted to learn how to dogsled. From an early age, Braverman, a child of Southern California, had been transfixed by the idea of the far north, of skiing toward the top of the world in the bracing cold, with just reindeer and the Northern Lights to guide her. Her teacher at the folk school had his teenage charges jump into a frigid polar river so that, by learning to force their ice-numbed limbs into action, they would be prepared to save themselves. It’s the only wisdom he had to impart, he later told Braverman: “how to be cold,” by which he meant, “How to live.”

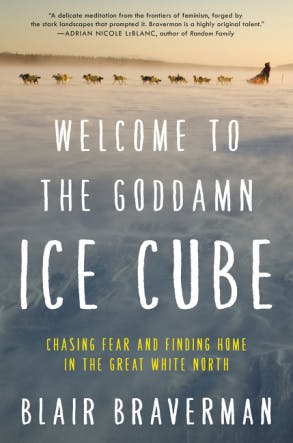

It’s a lesson she returns to repeatedly throughout Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube: Chasing Fear and Finding Home In the Great White North, a lyrical, time-skipping memoir of her adventures in the northlands of Norway, Alaska, and Wisconsin. More broadly, it’s a first-person meditation on what it means to come of age as a woman in a place that doesn’t accept your presence. “I’ve spent more than half my life pointed northward,” Braverman writes, “trying to answer private questions about violence and belonging and cold.”

The violence comes early. When Braverman first went to Norway at 10 years old, on a chance family sabbatical, she found a country so safe that mothers could leave their babies in strollers on the street while they shopped and young girls could explore from one end of the city to the other without a chaperone. It was, as her parents would later comfort themselves, “a good place for a girl.” But when Braverman returned to the country at 16, as a high school foreign exchange student, the intervening years had somehow made Norway less safe, at least for her. The father of the host family she’s placed with, a man she calls Far, watches her with a sexual aggression she only dimly comprehends; over the course of the year she stays, he goes on to touch her inappropriately, follow her to a friend’s house at night, and relish opportunities to physically and psychologically dominate her.

She becomes fearful, but worse, the ordeal plunges her into years of self-doubt. She second-guesses her own instinct that what Far did was wrong and that her corresponding anger was O.K. While her classmates see her as “a tough girl,” Braverman becomes her own victim, questioning herself “so violently that I split in two: the part that was afraid, and the part that blamed myself for my fear.”

For Braverman, these years are, like the landscape, stark and cold, exhilarating and terrifying. The north, in Braverman’s book, represents a lot. It’s the location of adventure and a chosen home, and as such, the setting for fulfilling personal ambitions and dreams. But the north she loves knocks her down repeatedly. It’s the backdrop for a brand of “hard masculinity” that doesn’t welcome women except as sexual distractions, and a place where Braverman strives, first, to prove and defend herself and, ultimately, to trust herself.

After Far’s hostility robs her of what was to have been the launching point for a self-made life of adventure, Braverman—how about that name?—determines that the solution is to go back “to the place I had yearned for, where I could prove I was the person I had once known myself to be.” At the folk school, she falls in love with dogsledding, a sport “in which the bulk of the action played out in secret”—as mushers disappear into the wilderness for solitary journeys across hundreds of miles—and where the things to be afraid of don’t lurk beneath the surface but are tangible and immediate—fears that don’t make her crazy, she writes, but brave.

But the sexual violence Braverman first encountered in Far’s home extends across the north. When she takes her new dogsledding skills to Alaska, to work as a musher at “Dog World,” a glacier-based tourist destination, she finds herself again a target. The mostly male staff stare at her when she walks, gape when she washes her hair in a pail of melted ice, dismiss her success with clients by suggesting she’s doling out blowjobs, and joke about catching her “alone on the trail.” She bundles herself in layers of Carhartts and men’s flannels, hopeful to go unnoticed. But ultimately, she fears, “in Alaska I would never be anything but a girl.”

That changes for a time when she begins dating a male coworker, Dan, and becomes an honorary member of what seems like “another gender entirely”—one where women are greeted as colleagues, with opinions that count and bodies that are left alone. For a time Braverman basks in the civility, but when her romance with Dan turns ugly—in an encounter it takes Braverman years to call rape—she again turns on herself, slipping into an unhappy long-distance relationship (“the path of least resistance”) and losing a dramatic amount of weight (“until I no longer recognized the body that Dan had fucked”). The following year, when she returns to Dog World and finally manages to break things off, Dan leads her coworkers in a campaign of silent retaliation, proposing that the situation will only “get better” if she relents and sleeps with him again.

Faced with the “bitter protection” Dan offered and “the exhaustive work of shielding myself alone,” Braverman chooses the latter. But it’s a choice that comes with a cost. “Turning down Dan—choosing jurisdiction over my own body—felt like choosing exile from the very things in which his approval had granted me legitimacy,” she writes. “The change Dan lamented was that I had started to trust myself. But the way I saw it, I had flunked out of the north.”

Although the world of female dogsledding is almost definitionally obscure, Braverman’s experience in it is not. Full disclosure: I know Braverman—she’s the partner of a friend, and we share a common circle of colleagues. When I published a story this spring about an epidemic of sexual harassment and assault in national parks and forests, Braverman noted how the experiences she’d had in Alaska and Norway paralleled those of the women I’d spoken to—firefighters in California and desert biologists at the Grand Canyon, all women trying to forge careers in wilderness fields where the sheen of wholesome benevolence associated with the outdoors obscured the hostility of traditionally male-dominated industries resistant to change. The stories those women told—of being repeatedly propositioned and harassed, having everyday experiences become distressingly charged, and pointed attempts to undermine their work or drive them out of their jobs if they complained or fought back—aren’t unique to any one field. They’re just cast into sharper relief because they’re happening in settings that are both isolated and revered.

“People ask me all the time if I’m scared in the wilderness. Because I’m a woman,” Braverman tweeted at the time. No, she answered, “I’m scared everywhere because I’m a woman. At least in wilderness I have space.” Or, as she writes in the book, “nothing that had happened to me—not Far, not Dan, not anything—was beyond the normal scope of what happened to women all the time. Some harassment by an authority figure, a few sexual remarks, pressure from an insistent boyfriend? What woman hadn’t experienced those things?” The water’s cold everywhere. Come on in.

“On the other hand,” she continues, “if I’d accepted the word rape, maybe I would have discovered other words, ones that could have helped me make sense of my earlier experience: dissociation, counterphobia”—that relentless return to a source of anxiety in the hope of finally overcoming it. It takes her a long time to begin enforcing boundaries and to learn how to navigate a threatening world: when to stop proving yourself, how to trust your instincts. These are the lessons of every coming-of-age story but they mean something more specific for women. Like the hostility and harassment Braverman finds in the north, they’re universal issues made more urgent in a landscape with fewer avenues of escape.

Ultimately, Braverman finds herself in upper Wisconsin, where, to her surprise, she becomes the expert at the center of a small community of dogsledders. She finds a sense of peace in small epiphanies: the shy, nervous dog who thrives when she’s placed at the head of the pack; the chaotic accident during a race she realizes she can fix. It’s how adventure stories are supposed to end. A decade after fleeing a country that seemed to turn against her, Braverman realizes she had made her own north.