Some time before the First World War my grandfather, Jack Baker, went to work for “Bathhouse John” Coughlin, the blustery Democratic boss of the infamous political machine in Chicago’s First Ward. Jack had been sent to farm an Indiana homestead, along with his brother and sister, after their mother died. There they were worked half to death, a common fate for hired-out children of the time. My grandfather and his older brother ran away, then returned for their sister, who they freed at gunpoint. But where were three homeless children to turn then? Why, to the First Ward, where Bathhouse John and his political machine would welcome them with open arms.

Coughlin was called “Bathhouse” because he reputedly got his start at the age of eleven as a masseur, or “rubber,” in a Turkish bath. He quickly grasped the economic potential inherent in such an institution, and eventually accumulated enough money to buy a brace of bathhouses. Coughlin and his partner, Mike “Hinky Dink” Kenna, also took a financial interest in—meaning they collected protection money from—saloons throughout the First Ward. Soon, the two men had a foolproof system going. Anyone out of work or down on his luck—say, a man who had fallen into the bottle—could show up at one of their saloons and find cheap lodging at one of their bathhouses. Come election day, the grateful lodger would be trotted out to the local polling place with an already-filled-in ballot hidden in his pocket. There, he would accept a clean ballot from a poll worker, slip the already-completed one into the box, and return to the bathhouse, where he’d be paid 50 cents or even a dollar for the clean ballot. The fresh ballot was then filled in by bright young lads like my grandfather, who were eager to move up the ranks of the machine, and handed back to the bathhouse legion. Then off the lads would go to another polling place, to repeat the process for as long as the polls were open.

Thanks to the largesse of the machine, my grandfather went on to serve in the Great War, taught himself to be an accountant, and ended up a useful citizen and beloved father of seven. Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink remained what they were: corrupt by almost every definition of the word, avatars of a more brutal and cutthroat American age. But from a purely electoral standpoint, they were also incredibly successful. Coughlin was elected alderman 20 consecutive times, serving 46 years before he finally died of pneumonia in 1938. Hinky Dink was in and out of the city council until 1943, three years before he moved on to one of Chicago’s graveyards, which were legendary for their strong election-day turnout.

Democrats, and America, could use men like them again.

When Barack Obama came into power in 2008 with large majorities in both houses of Congress, it was hailed as the beginning of a new and lasting era of Democratic rule. Two years later, Democrats lost six U.S. Senate seats and 63 House seats—their worst beating in the House in 72 years. They also lost 680 seats in state legislatures, an all-time record, and six governorships. The 2014 midterms were no better: Democrats lost nine more Senate seats—their worst showing since the Reagan Massacre of 1980—plus another 13 House seats, and forfeited a net of two more governors’ mansions and eleven more legislative chambers. The party was reduced to its lowest standing on the state and national levels since 1900—and is now so feeble that it cannot even force the Senate to fulfill its constitutional mandate to hold hearings for an empty seat on the Supreme Court.

How is it possible for Democrats—seemingly the natural “majority party,” on the right side of every significant demographic trend—to suffer such catastrophic losses? Explanations abound, most of which revolve around the money advantage Republicans derived from the Citizens United decision. Or the hoary, self-congratulatory fable of how Democrats martyred themselves to goodness, forsaking the white working class forever because it passed the landmark civil rights bills of 1964 and 1965. Or how the party must move to the left, or the right, or someplace closer to the center—Peoria, maybe, or Pasadena.

But there’s a more likely explanation for these Democratic disasters. While 61.6 percent of all eligible voters went to the polls in the historic presidential year of 2008, only 40.9 percent bothered to get there in 2010, and just 36.4 percent showed up in 2014, the worst midterm showing since 1942. What the Democrats are missing is not substance, but a system to enact and enforce that substance: a professional, efficient political organization consistently capable of turning out the vote, every year, in every precinct.

What they lack is a machine.

New York’s Tammany Hall, the first, mightiest, and most feared of the political machines, went online on May 12, 1789—less than two weeks after George Washington took the oath as president in the same city.

The Society of St. Tammany was named for Tamanend, a legendary chief of the Delaware who had obligingly signed much of his people’s land over to William Penn. Tammany always had a populist tinge. It was founded as a counterweight to the Society of the Cincinnati, a club started by Washington’s officers that many feared would serve as the seedbed of a hereditary American nobility. Tammany, by contrast, adopted many of the trappings of the French Revolution, with the Phrygian cap and admonitions such as “no slave nor tyrant enters” carved over the portals of its clubhouses.

The society’s first “grand sachem,” or ultimate leader, was one William Mooney, an upholsterer who entered a float into Washington’s inaugural parade up Broadway that depicted him in the act of cushioning a chair for the new president. Later, Mooney would be accused of having deserted to the British during the war, and he was driven from his grand-sachemship for looting $5,000 from the public almshouse to provide—as he put it—“trifles for Mrs. Mooney,” thereby sealing the machine’s reputation for both chicanery and self-promoting spectacle.

Yet the man who turned Tammany into a full-fledged political machine never actually joined the society: that murky intriguer, Aaron Burr. By 1799, Alexander Hamilton and his Federalists held a virtual monopoly on banking in New York, frustrating smaller businessmen who wanted to start their own banks and “tontines”—investment companies that would not only make them money, but also get around property requirements that kept even most white men from qualifying for the franchise. Burr marched a bill through the state legislature that created the Manhattan Company, which promised to slake the island’s thirst for a dependable water supply. But Burr slipped a provision into the bill that allowed the company to invest any excess funds however it desired—which was the legislation’s main purpose all along.

The upshot was that the Manhattan Company laid down a lot of water pipes that were little more than hollowed-out logs. They leaked badly and absorbed sewage, thus contributing to the city’s constant, deadly epidemics of cholera and yellow fever. But Burr’s company used the money it made from the scheme to found the Manhattan Bank (later to become Chase Manhattan, later to become JPMorgan Chase). The Hamilton banking monopoly was thus broken, and new banks and tontines proliferated, allowing financial speculation to run wild, and untold numbers of middle and working-class New Yorkers to gain the franchise for the first time. In this one coup, Burr established the defining characteristics of political machines for all the years to come: They would be first and foremost about making money, no matter the cost to the general good; they would supply significant public works, no matter how shabbily or corruptly; and they would expand the boundaries of American democracy in the face of all attempts by conservatives or reformers to contain it.

Those leaky pipes and other such shenanigans put Tammany into eclipse for a few years. But “the organization”—as machine leaders preferred to call it—began its recovery on April 24, 1817, when the future arrived in the form of a mob of Irish-Americans, who literally stormed Tammany’s meeting hall and smashed up the place. The Irish were enraged that the society had refused to endorse the popular, Irish-born orator, Thomas Addis Emmett, for Congress. From the start, Tammany had limited its membership to “pure Americans,” meaning native-born citizens. But now that changed in a hurry. The machine had just been crashed by a perfect growth opportunity: immigrants.

Although they had been arriving in large numbers since the beginning of the nation, the 1845 Irish potato famine sped up the influx. By 1860, 200,000 people, nearly one-quarter of the city’s population, were Irish Catholics, many of them often illiterate and unable even to speak English, transforming what had been an overwhelmingly Protestant, Anglo-Saxon city. Other convulsions in Europe would bring waves of Italians, Eastern European Jews, Poles, Slavs, and others. Instead of renouncing or attacking them, Tammany recruited them.

“Think what New York is and what the people of New York are,” declared Richard Croker, the machine’s ruthless, rough-hewn leader. “They do not speak our language, they do not know our laws, they are the raw material with which we have to build up the state.… There is no such organization for taking hold of the untrained, friendless man and converting him into a citizen. Who else would do it if we did not?”

Immigrants provided Tammany with an army. By the Civil War, most cities in the United States had at least one political machine. While some places, including Chicago, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati, boasted competing organizations from each party, the machine was primarily a Democratic institution. Republicans carried the taint of the anti-immigrant, Nativist, and Know-Nothing parties they had absorbed, and the GOP was made up largely of men who were geographically as well as temperamentally more difficult to pack into a machine: yeoman farmers, small businessmen, entrepreneurs.

What’s more, Republicans have always been, for better and for worse, the truly radical party in this country, from the abolitionists and Lincoln’s “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men” platform, to Progressivism and Teddy Roosevelt’s “New Nationalism,” to the right-wing conservatism of Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, to the Ayn Rand utopianism of Paul Ryan. By contrast, machines made Democrats—again, for better and for worse—the party of compromise and inclusion.

By the late nineteenth century, the clients had taken over the company. The leaders of Tammany were now largely the sons of Irish Catholic immigrants, though as the historian Arthur Mann wrote in 1962, machines were also “headed by Germans in Saint Louis, Yankees and Scandinavians in Minneapolis, Jews in San Francisco—or in our own day by Poles in Buffalo and Italians in Rhode Island.” Sometimes, when the Irish had too much of an advantage in numbers, as in James Michael Curley’s Boston, they rode roughshod over later immigrants, turning the city’s politics into a poisonous grudge match between Micks and Yanks—or what the Irish liked to sneeringly call “the codfish aristocracy.” But in more diverse cities, such as New York, ward bosses learned to welcome others from all over Europe, and to bring them up in the organization. “Big Tim” Sullivan, the longtime sachem of New York’s Bowery, would brag about “my smart Jew-boys.” George Washington Plunkitt, the remarkable West Side boss with “three winters” of grammar school, whose reflections on the machine, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall: A Series of Very Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics, would become a staple of college poli-sci classes, described one Johnnie Ahearn, whose “constituents are about half Irishmen and half Jews. He is as popular with one race as with the other. He eats corned beef and kosher meat with equal nonchalance, and it’s all the same to him whether he takes off his hat in the church or pulls it down over his ears in the synagogue.”

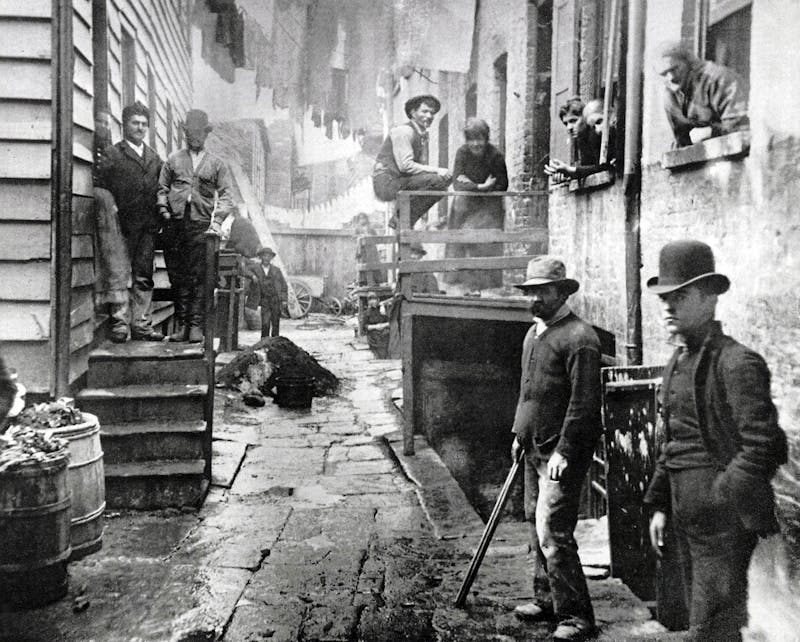

You might not have been interested in the machine, but the machine was interested in you—how it could serve you, win your vote, win your participation. It provided immigrants with jobs, clothing, and the proverbial turkey for Christmas; got them their citizenship papers; bailed them out of jail; advanced them money for a wedding or a new child; sent them a doctor when they were sick; buried them respectably. Providing these services—and finding out in the first place what their constituents needed—required copious man power, with still more hands required to canvass the vote, stand on street corners and bloviate, and physically haul the faithful to the polls to vote “early and often”—not to mention strong-arm opponents, intimidate vote counters, and, if necessary, steal away entire ballot boxes and dump them in the river.

Politics under the machine was an urban festival, with picnics and chowders, boat rides, excursions to the country or the new amusement parks, balls and cotillions, block dances, and “beefsteaks,” atavistic rituals in which men donned aprons and devoured endless amounts of buttered steak with their teeth and hands.

In Chicago, Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink ran the “First Ward Ball,” an annual “racket” that was a common machine tactic for raising money. Everyone under the organization’s sway or who wished to curry favor with its leaders would buy tickets. Police captains and city leaders would rub shoulders with brothel keepers and gangsters. At midnight, the lavishly festooned Coughlin—a typical outfit included “a green dress suit, mauve vest, pale pink gloves, yellow pumps and silken top hat”—would enter at the head of the ball’s grand march, accompanied by the city’s two leading madames, and followed by a procession of masked, drunken revelers in expensive and highly revealing costumes.

The machine insinuated itself into almost every part of urban life. It held regular meetings in the corner saloon, invariably owned by some ward boss like Hinky Dink. (That was a primary reason so many progressive reformers backed Prohibition—to shut down the machines.) It helped organize volunteer fire companies, and took over the police and most other municipal jobs, doling them out to loyal members—in return for a generous contribution to the party coffers. It provided, not least, a career for the millions of bright young Irishmen, Italians, Jews, and other immigrants who were often unable to get more than an eighth-grade education—and who, if they had, were still barred from most of the top law partnerships, medical institutions, and financial firms.

Between 1865 and 1924, the successive bosses of Tammany Hall, who presided over thousands of workers in the nation’s greatest city and handled untold billions of dollars, started out, respectively, as a chair maker’s apprentice, a soapstone cutter, a day laborer, and a horsecar driver. Plunkitt, born on Nanny Goat Hill in what is now Central Park, began work in a butcher shop at age eleven. Big Tim Sullivan took to the streets at eight, as a newsie. Al Smith, that brightest star of the machines, elected governor of New York four times, went to work at the Fulton Fish Market at 14. The machine—and only the machine—provided something better.

The trouble with politics as a business was that it required a dependent and subservient population. The machines had no interest in reducing the numbers of the urban poor, or enabling them to find worthy careers outside of politics. That would mean fewer voters, fewer foot soldiers heeling the ward. The machines were also hugely, grossly corrupt—the more so as the American economy expanded and the opportunities to grab proliferated. The organization was always in bed with organized crime. One of Big Tim Sullivan’s “smart Jew-boy” protégés was none other than the mobster Arnold Rothstein, and Big Tim was part of a criminal syndicate supposedly collecting payoffs from every whorehouse, dice game, race course, and pool hall in the city. The Sullivan Act of 1911, New York’s seminal gun-control statute, was passed not because there were so many gun murders—there weren’t—but because it was an ideal way to control the gangsters Tammany utilized for special tasks. A cop could plant a gun on any mobster who forgot himself, and haul him in to serve time.

But when Prohibition made organized crime richer than it had ever been—an unintended consequence of the drive to “break up the saloon”—the whip changed hands. The mob controlled the politicians, to the point where the 1950 New York mayoral election was considered little more than a contest between the Genovese and Lucchese crime families.

Perhaps the worst flaw of the machines was how often they actually reduced opportunities, and even standards of living, for their constituents. A major scandal burst in 1900, when it was found that crooked elements of New York’s Croker machine had helped a single company gain a monopoly on ice—then a vital necessity of survival in the slums—and double its price. For decades, all along the waterfront of New York Harbor, Tammany and the notorious Jersey City boss Frank “I am the law” Hague kept tens of thousands of poor, mostly Irish and Italian dock workers and their families in penury, murdering union dissidents and looting the busiest port in the world so ravenously that they hastened its demise.

Plunkitt made a great distinction between what he called “honest graft”—using inside information to scoop up land where some new development was planned, or awarding his own contracting company lucrative municipal jobs—and dirtier business. But most were not so particular. The machines effectively forced police to shake down brothels, bars, gambling dens, and even perfectly legitimate businesses. Cops had shelled out large sums of money to the machines—often a year’s salary or more—to get on the force in the first place, and they needed to kick back ever larger sums of money if they were to advance in their careers.

These shakedowns and countless others served as a running tax on businesses, and businesses in return demanded and received services for their money. What this meant became apparent in 1909, when New York’s garment workers walked off the job. The machine turned out the police to crush the strikers, who were overwhelmingly young women, usually from immigrant families. The police, in turn, brought along the prostitutes they controlled and, in an appalling ritual, forced them to start fights with women walking the picket line—whereupon the garment workers were clubbed and hauled off to jail for disturbing the peace.

This ugly spectacle turned much of the city against the bosses. Wealthy women came out to march with their “sisters” on the picket line, stymieing the police. Much worse for the machine, the backlash endangered its main source of votes and foot soldiers. Afraid that the immigrants now filling up American cities in greater numbers than ever before would start voting for socialists and other reformers, Big Tim Sullivan and his allies up in Albany used the tragic fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911 to join forces with the reform social worker, Frances Perkins, and pass landmark legislation to protect worker wages, rights, and safety.

That triumph, according to Perkins—later the first female labor secretary and a co-author of the Social Security Act under FDR—marked the start of the New Deal. Many young reformers followed her lead, either bypassing the machines entirely or forcing them to think more broadly about how to benefit their constituents. In the 1920s, when Al Smith was governor, he turned the state into a laboratory for social reform and recruited liberals and progressives from outside the machine—including FDR himself, who made his political bones attacking Tammany. Across the country, as the power of the machines began to ebb, local bosses raised up sterling, incorruptible individuals to high office: Smith in New York, Adlai Stevenson in Chicago, Abe Ribicoff in Connecticut, Harry Truman in Kansas City. The machines remained corrupt to the core, but the statesmen they now elected to prove their respectability went on to transform American politics.

Such attempts to oil up the machine, however, proved to be its undoing. The New Deal put paid to it by building a social welfare state in America, and liberal legislation from the G.I. Bill to the Great Society drove the final nails into the coffin. There was no need for the machine to get you a job when the government was waiting with scholarships and loans to see you through college, and when union wages enabled you to buy your own damned Christmas turkey. Slowly but surely, antidiscrimination laws opened doors—sometimes literally, as with the 1968 Fair Housing Act—making it easier for immigrants and working-class Americans to get an education, a job, and a home, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexual orientation.

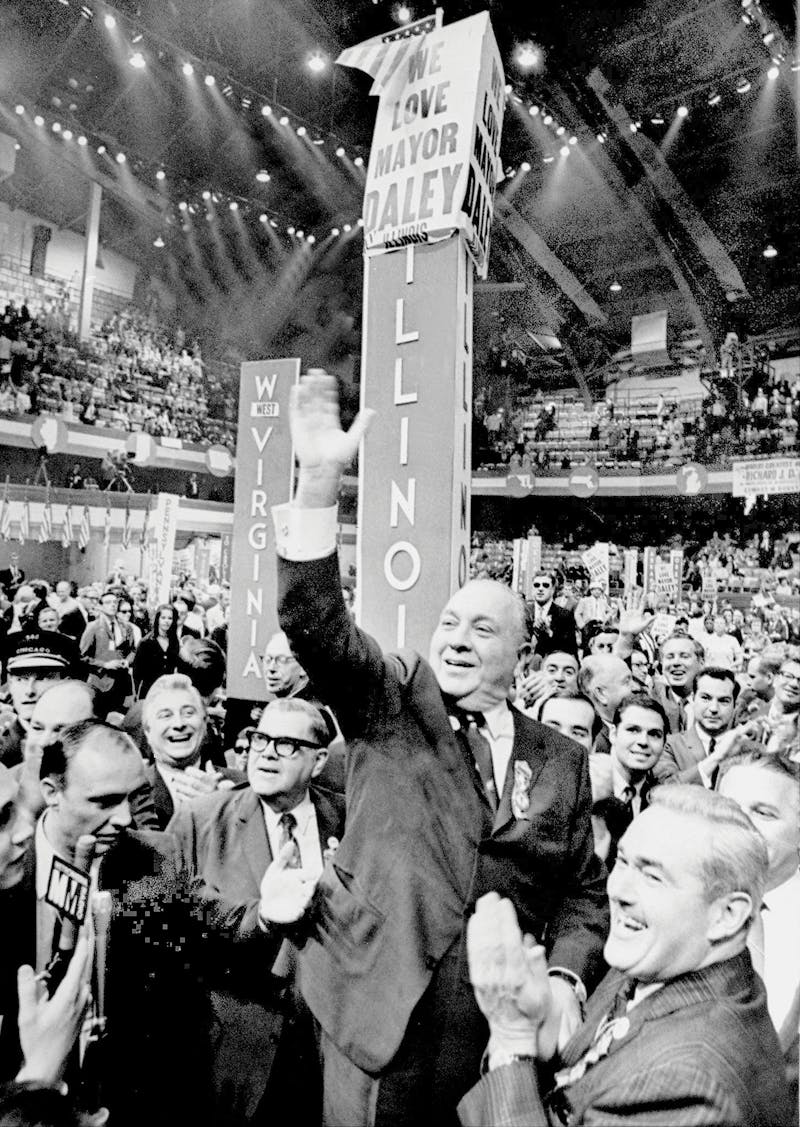

The machine’s old dependents were not only no longer dependent, they weren’t even there any longer. They were moving out to the suburbs, leaving only the rich, the rebellious young, and people of color—three groups the machine had little interest in or ability to control. Richard Daley, who took over Chicago’s machine and mayoralty in 1955, had been a teenage member of the Hamburg Athletic Club during the horrific 1919 race riot in Chicago, when the Hamburgs had run amok. As mayor he used federally funded projects—such as the Dan Ryan Expressway—to keep Chicago rigidly segregated. In New York, the machine even joined forces with its old antagonist, Robert Moses—an inveterate racist—to devote federal monies for “slum clearance” to the real project of “Negro clearance.”

By the 1960s, even the mightiest machines were grinding to a halt. The Tammany tiger finally ran out of lives in 1961, put down for good by a coalition of Greenwich Village rebels, whose ranks included Eleanor Roosevelt, Jane Jacobs, and Ed Koch. Even Daley’s notorious Chicago organization, the last one standing, was no longer a machine in the old sense, surviving only on a combination of ruthless efficiency and ethnic resentment. The turmoil at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago completely unhinged Daley, who was caught by the cameras screaming “you fucking kike!” at Senator Abe Ribicoff on the convention floor, a previously unimaginable violation of machine etiquette.

Its death, however, did not stop politicians from continuing to rage against the machine. The silliest example of all is the fervent Republican contention that Barack Obama brought “Chicago politics” into the White House, as if the president learned his trade at Dick Daley’s knee. What they really mean by “the machine” is whatever clique of state legislators or local pols have figured out some new means of boodling public funds or soliciting bribes. But that’s simple theft. Today our politicians don’t steal because the machine helps them, but because we have ceded them the entire political system—as reflected in our miserable voter turnouts.

So the machines died, their demise hastened by the sweeping social revolutions of the 1960s and ’70s, which made them look reactionary and ludicrous—pudgy gray men in gray suits and hats, holding back the future. Good riddance. But what was to replace them? For a short time, it was constituent groups: disparate organizations fighting for civil rights and liberties, environmental causes, the poor and the dispossessed, community empowerment, and above all labor, which provided the bulk of the party’s funding and its ground troops. But this new arrangement soon began to unravel as well. As Thomas Frank points out, “Big Labor” was viewed as suspiciously by the Democratic left as the machines were, scourged for its cultural conservatism and support for the Vietnam War, caricatured as hopelessly mobbed-up and resistant to progress.

For the most part, Democrats watched as labor was all but destroyed, collaborating in the creation of the paper economy—a colossal mistake that the party has never fully recovered from. The remaining constituent groups proved incapable of replacing labor as the core of a modern, liberal party, or deciding if they should even take part in electoral politics. Emerging as most of them did from a 1960s political culture wary of “selling out,” these new Democrats were reluctant to commit to any greater coalition, and thus wound up delegitimized by the right as “special interest groups.”

With the traditional pillars of their party crumbling, the Democrats turned to that balm for all political wounds in America: big money. In the process, they further abandoned their traditional populism, as well as their appeals to working people—appeals that, however imperfectly, stretched all the way back to the start of the machines. And those few leaders in the party who weren’t pandering to corporate and financial interests began to think in idealistic terms that have nothing to do with “practical politics,” habits that prevail to this day. For many years now, liberal/left campaigns have rarely revolved around specific bills or policies, but instead around broader and more abstract demands: climate change, say, or racial equality. The Occupy and Black Lives Matter movements have proven to be balky, fitful vehicles for social change. They lack the ruthless practicality and organization of their right-wing counterparts. Occupy invented the human microphone. The Tea Party took Congress.

If the machine was our party system at its most corrupt, it was also at its most efficacious. It gave form to our ideals. Interviewing a clutch of Tea Party activists last year, I was struck by the fact that nearly all of them had started out as grassroots activists, and then made their way up a ladder provided by the right-wing moneymen to become full-time organizers—with the promise of even more lucrative and fulfilling careers, in and out of government, still to come.

For nearly 50 years now, the right has painstakingly built its own party infrastructure. The number of corporate PACs and right-wing lobbyists in Washington has grown exponentially since 1968. Corporate lobbying money grew from an estimated $100 million in 1971 to more than $3.5 billion by 2015. The Koch brothers poured money into right-wing and libertarian think tanks and the Tea Party. By the height of the Bush administration, conservative think tanks outnumbered their liberal counterparts two to one, and outspent them nearly four to one. The right, in short, has built the twenty-first-century equivalent of the old machine.

So how can Democrats get back in the game of practical politics? The trick is to take the best of what the machines gave us—the populism, the participation, the inclusion—while avoiding the old venality, racism, authoritarianism, and exploitation. This was never any mean feat, and the task has been too long delayed. But drawing on history, one can suggest some guidelines for building a modern-day political machine:

Start at the bottom. The machine bosses might let their brightest pupils shine down in Washington or up in the governor’s mansion, but they were most interested in winning state assembly races, or holding offices that most people never think about, such as street commissioner. This is where true power lies. Look at how much Republicans have done to suppress the vote just by holding obscure offices at the state level, such as secretary of state—Kenneth Blackwell in Ohio, Katherine Harris in Florida—or attorney general. Greg Abott, the current Texas governor and former attorney general, spelled out how the GOP’s strategy shaped his workday: “I go into the office, I sue the federal government, and I go home.” There’s a reason why most of the $889 million the Koch brothers plan to pour into this year’s election will go into races that will determine control of state and local governments, and the Congress.

Liberals, by contrast, still tend to put their best efforts behind issues—to stop fracking or the Keystone pipeline, police the police, or raise the minimum wage. That’s commendable, but to elect your own people at every level of government is to change the agenda and culture of democracy everywhere. Take a single example: If liberals wielded a majority in the New York state legislature, they could institute congestion pricing in New York City, not only unclogging its streets, but creating a permanent source of financing for the city’s vital mass transit system. That, in turn, would mean lower transit fares, jobs for construction-union workers to make badly needed infrastructure improvements, more disposable income for poor and middle-class families, a better business environment, and—oh, yeah—one more way of slowing climate change. Thus, from the bottom up, an entire agenda is achieved.

Don’t wait until election years to recruit. The machines were organized down to the block level—sometimes to the apartment-house level, with layer upon layer of committees and “ward heelers.” The organization had to do this: It needed your vote. Today, in an average, gerrymandered election district, congressional representatives are trotted out only at election time, like Hindu priests hauling out the juggernaut for Ratha Yatra. That won’t win local or statewide races. Democrats must actively recruit, as the machines did, block by block, building by building.

Michael Dukakis recently told me that his inability to institute an effective, grassroots organizing system was as much to blame for his failed 1988 presidential bid as the infamous “Willie Horton” ad that Republicans had famously used to slime him. “The only reason I got elected governor three times, and to the state assembly before that, was precinct-based, grassroots organizing. By which I mean a precinct captain, and six block captains, making personal contact on an ongoing basis with every single voting household in the precinct,” explained Dukakis, sounding very much like an old ward boss. “It wasn’t until Obama came along that we really had a serious, precinct-based organization, at least in the battleground states, and I don’t think there’s any question that Obama was elected and reelected because of it.”

He’s right—but the efforts of a single candidate are no substitute for a machine. The president handed “Obama for America” over to the Democratic National Committee, which promptly renamed it “Organizing for America,” drained any remaining life out of it, then waited a decent interval before taking it out to the back pasture and putting it down.

Build a program. When Al Smith moved into the governor’s mansion in New York, he hired visionary, politically savvy advisers from outside Tammany circles who were willing and able to shape liberal agendas on everything from working conditions and public parks to highways and old-age insurance. They constituted a pocket lobby, able to draw up legislation that was truly transformative.

There are no Al Smiths today, but there is ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, which assembles ready-made legislative acts for GOP legislators to vote into law, usually on behalf of corporate clients. ALEC has annual gross receipts that reached nearly $8 million in 2014—with another $25 million a year from its more than 300 corporate sponsors. Every year, ALEC’s 2,000 members—one in every four state lawmakers—introduce some 1,000 pieces of right-wing legislation provided by the organization, and pass, on average, 170 of them. ALEC has helped make “Stand Your Ground” the law in 33 states, passed “health care choice” bills challenging Obamacare in another dozen states, and is pushing voter suppression laws everywhere.

Liberals have tried to forge a similar operation, with several “model legislation” groups merging to form the State Innovation Exchange, or SiX. But thus far, it’s more a wind-up toy than a machine. SiX remains a mishmash of groups that can’t seem to get its act together. It’s as if the old Tammany bosses simply sat around testing brand names and mission statements, while a bunch of millionaires ate their lunch.

Grow the grassroots. The machines knew something that Democrats have forgotten: that any successful operation must start by understanding and responding to the needs of its constituents. By refusing to respond adequately to growing inequality and the changing nature of work, today’s Democratic non-bosses are in danger of becoming just as antiquated and irrelevant as their machine-era predecessors. We need a Tea Party—less doctrinaire, less delusional, less hell-bent on destruction—that can do what the machines did: Hold liberal legislators accountable when they neglect their constituents and instead give their hearts and votes to the most destructive forces in our society—Big Money, Big Pharma, Big, Big, Big.

Pay attention to the quid pro quo. In the machine days, this was simple: a turkey at Christmas, a room for a homeless boy. Today, much of what the old machine did would be seen (rightly) as extortion, bribery, and worse. But that’s still no reason why liberals can’t imitate the myriad ways Republicans have devised to reward the faithful.

Simply put, Democrats are going to have to suck it up and pay people. Talented operatives have to see the hope for a career in party politics: a chance to make a decent living, develop ideas, and see them brought to fruition—all things that Republicans can count on. It would mean many more paid positions within the party itself, jobs devoted to actively recruiting members. And it would mean a national pay structure for the Democratic Tea Party we need to build.

Politics, like any war, is best conducted by professionals. But liberals and the left continue to place their hopes in “outsiders” and “insurgents,” amateurs who rail against the system without the means to reform it. The Green Party, for example, has embarked on yet another presidential campaign to nowhere; as its presumptive nominee, Jill Stein, recently boasted to The Village Voice, “I’m a physician, not a politician.”

Stein seemed to consider this a point of pride. George Washington Plunkitt would have set her straight. “Politics is as much a regular business as the grocery or the dry-goods or the drug business,” he observed. “You’ve got to be trained up to it or you’re sure to fail.”