The middle of the 20th century was a golden age for the American theater. Tennessee Williams wrote his first masterpiece, The Glass Menagerie, in 1944, towards the end of World War II, and A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof both followed in the subsequent decade. Eugene O’Neill wrote his titanic mature works, Long Day’s Journey Into Night and The Iceman Cometh, during World War II, and each was first performed in the first dozen years after the war. And in the same period, Arthur Miller gave the world arguably his greatest works: All My Sons, Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, and A View From the Bridge.

These plays are the mainstay of the American theatrical canon, the ones that the greatest actors of every generation seek to leave their mark on, and make their own.

But are they still our own?

A series of recent productions that came to New York with great acclaim have implicitly questioned whether we can still see these plays for what they are, or whether they need to be made new to avoid seeming stale. These productions took plays that are deeply rooted in a particular time and place—and that deal, urgently, with the issues of their day—and ripped them up forcefully to re-pot them in fresh soil.

In foreign soil, one might say, as the three productions I’m thinking of in particular were directed by Europeans. This approach, of course, is not unique to European directors. For well over a generation, American directors have been taking Shakespeare’s plays and setting them wherever and whenever they like—whether in a particular time and place, or an abstract nowhere, or a cosmopolitan everywhere that partakes of whatever bits of history and culture that may lie to hand. The Oregon Shakespeare Festival has even famously (or infamously) commissioned translations of Shakespeare into more familiar English. For these classic works, whatever enables the audience to connect to the character and story is fair game.

What’s new is applying that approach to American classics. If these European directors are right, and these plays need a kind of translation to come fully alive, what does that say about our relationship to theater—and our relationship to our own past?

Chief among these recent productions are Belgian bad boy Ivo Van Hove’s twin Broadway triumphs with Arthur Miller: A View From the Bridge and The Crucible. A View From The Bridge is a kind of Sophoclean tragedy, which was Miller’s explicit intention. He wanted to show that among the ordinary people of his day, dramas were playing out as grand as those of Oedipus and Antigone. The play tells the story of a man, Eddie Carbone (played by Mark Strong in Van Hove’s production), who cannot acknowledge his desire for his niece (played by Phoebe Fox). In the process of keeping that secret from himself, he destroys both himself and his family. It’s a play deeply entrenched in the world of Brooklyn’s Italian longshoremen—a world long gone that cries out for re-creation. But it also employs theatrical conventions—the lawyer, Alfieri, acts as a kind of chorus figure—that can be read as profoundly dated, particularly when they have to live within the confines of period reconstruction.

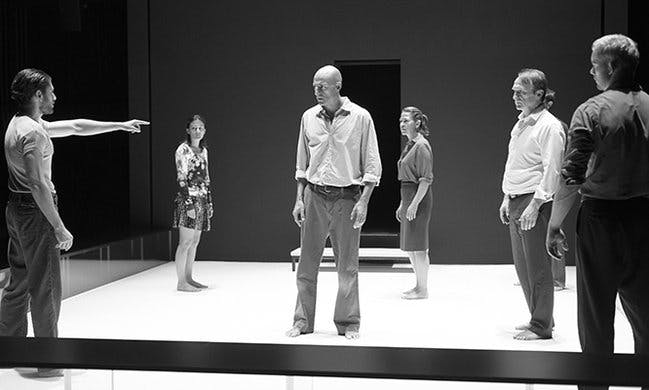

Van Hove’s approach is to set the play in a no-place, a symbolic theatrical space that could not be mistaken for naturalistic reality. The stage is a stylized, abstracted version of a boxing ring in which the characters circle. The characters’ clothes do not particularly evoke the period, and their missing shoes make them seem even more like creatures of an abstract world. Even the style of the acting is divorced from the conventions of American naturalism—with such frequent and lengthy pauses, I felt like I was watching Pinter rather than Miller.

And I was absolutely riveted. The drama of this family felt absolutely real, but more to the point, I felt no distance from them. As it happens, though the play is rooted in the period when it is set, it deals with themes and situations that are extremely relevant to our moment in history. A major part of the plot turns on hiding from the immigration authorities, and the central problem of foster- or step-fathers showing sexual interest in their adolescent female charges is far from unknown in our day. But because of the abstract setting, the audience never has to make the leap of saying, “Oh, that world feels more like our world than I would have thought” because it is never presented as a foreign world to begin with. Precisely because it is set nowhere, we see these people for who they are, psychologically, without the mediating scrim of history. It does not feel like a mid-century attempt to replicate Greek tragedy. It feels like a Greek tragedy.

Van Hove’s version of The Crucible is even more radically innovative—and even more successful. The Crucible is an explicitly historical play in two ways. First, it is set in seventeenth-century Salem, Massachusetts, and Miller took some pains to use language that would have been appropriate to the period (while still taking dramatic license with the actual events and characters). But more so, Miller chose the period to make a connection between the witch trials of early American history and the public effort to expose and banish Communists from American public life under the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, culminating in the McCarthy hysteria.

The Crucible has long been a mainstay of high school English curricula and drama clubs precisely because of its utility for teaching about two periods in American history, and because it shows how a play can use history to confront its audience. But for the same reason, it has often appeared a tame and rather pat civics lesson on the stage. It comes off, too often, as a play that has a lesson for us, and the audience dutifully learns its lesson rather than experiencing the drama.

Van Hove seems to have understood this problem. He dispenses with any suggestion of a colonial New England setting. But he doesn’t set the play in a no-place. Instead, he sets it in a girls’ high school. When we first meet Abigail (played by Saoirse Ronan) and her fellows they are wearing plaid skirts and white shirts. They sit facing enormous blackboards, singing a hymn. The moment is redolent of cinematic cliches, from horror movies to pornography, that are entirely apropos. After all, The Crucible is about accusations of witchcraft, and the plot turns on an inappropriate sexual relationship between a married man and a teenage girl.

But the setting recalls something else: the context in which Americans usually first encounter the play, in the classroom. Right up front, the production seems to be saying: You are expecting a lesson. Instead, you’re going to have an experience.

And the character of that experience is the most radical choice of all. If there is one thing I feel comfortable assuming about the audience for any modern production of The Crucible, it’s that they don’t believe in witches. The play is explicitly about the madness of crowds who come to believe transparent absurdities—and the audience comes in agreeing that the accusations are absurd. So from what angle are they likely to experience that madness? They are likely to identify with John Proctor (played by Ben Wishaw), the level-headed farmer who knows that it’s all madness, because he knows Abigail is doing all this in an adolescent bid to revive their sexual relationship.

But we’re not supposed to be John Proctor. We’re supposed to be ordinary people in the town. And if that’s our position, then we have to be vulnerable to the possibility of dark, supernatural forces at work—because the townspeople are. Van Hove’s production gives us the opening to that possibility by using familiar horror-movie tropes that lure us into a comfortable suspension of disbelief. Then, from that standpoint—seeing people levitating and thrown against walls, furniture overturned and windows blown in, strange writing appearing on blackboards of its own accord, and a ghostly light pouring in from no obvious source—from that standpoint, he asks us to remember that John Proctor is the sane one, that we know Abigail is lying, and that there are no such things as witches.

Because he eliminates the mediating distance of history, I didn’t look down on the benighted people of Salem who believed such nonsense. Which we shouldn’t do, because we believe nonsense, too, when it plays to our own fears.

Moreover, precisely because I wasn’t thinking about Proctor as a figure in a historical drama—someone playing a role—I focused on him as a man. And when I did, I saw a play at heart about one man’s infidelity, and his inability to forgive himself for it. That’s far better ground for genuine empathy than having him be an alabaster martyr—and, for that matter, a better lesson in where true strength of character actually comes from.

Van Hove wasn’t the only European taking these kinds of liberties with American classics this past season—nor is Arthur Miller the only mid-century master to get the treatment. British director Benedict Andrews’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire played at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn this past spring. Not a trace of the romance of old New Orleans remained in Andrews’s play, which transplanted Williams’s fragile flower from a magnolia-scented past to an Ikea-decorated present stinking of cheap vodka. But what startled me is that the plant thrived under the harsh light—it perhaps grew far fewer flowers, but its stalk was firm and bristled with thorns.

Streetcar often plays as Blanche Dubois’s tragedy, and her relationship with her sister’s husband, Stanley Kowalski, as a kind of pas-de-deux, each recognizing that the other has something that they cannot fully fathom, that attracts them, even potentially completes them. In these productions, when Stanley rapes Blanche, it’s the final, violent evidence of Blanche’s tragic unfitness for this ugly world, and Stanley’s own behavior afterwards reveals a guilty conscience about what she released in him.

But Stanley (played by Ben Foster) is the rightful lord of Andrews’s world, while Blanche (played by Gillian Anderson) is not so much a tragic, romantic figure as a pathetic one, an alcohol-soaked fading Southern belle. Her dalliances with adolescent boys no longer read as the bursting out of desires banked too long, but as the utter collapse of self-control—and inevitably recall familiar news stories about female teachers and underage male students. Blanche’s rape is staged as brutally as I’ve ever seen, and its aftermath is as horrifyingly realistic: she is legitimately terrified even to see her brother-in-law, and has to be physically restrained by the mental health workers who come to take her away. What Williams allowed us to read as symbolic, Andrews forces the audience to look at square in the face—to see not the tragedy but the horror, and to recognize that the horror is the stuff of daily headlines.

What unites these productions is their absolute commitment to the present, and to the experience of the audience. These are productions that are not content to ask: What was the author’s intent with this play? Instead, they wonder: Who are these people, now, to us? Would we know them if we saw them? How can we come to know them, as directly and clearly?

A huge amount is gained this way. When I go to the theater, more than anything I go to feel something, and these productions made me feel pity, terror, and compassion in a way that few plays do.

But something is lost as well. To begin with, there’s the educational aspect. We continue to mount classic plays not only because they are abstractly “great” but because we want to remain in touch with our past. To an audience already familiar with these plays, these radical departures may breathe new life into stale texts. But will an audience that has never seen The Crucible even understand what the play is about from Van Hove’s production? And isn’t that an important consideration as well?

Education, of course, can be handled in other venues. But it still says something disturbing and important if the most direct way into these plays, psychologically, requires going around history rather than through it. If nothing else, it says that the world of mid-century is sufficiently far from our lived reality that it is now part of the undifferentiated past, an inevitably foreign country.

If that’s the case, then part of the job of these plays will be, increasingly, to make that foreign country familiar again. That means that historically sensitive productions will need to change, even as other productions take greater and greater liberties in the interest of reaching the audience where it lives.

What kind of change do I mean? The best way I can illustrate it is by reference to a production of a much older play that deals with history: Shakespeare’s Richard III. At the time it was written, the history depicted was recent and widely familiar. Shakespeare played very fast and loose with history, but for good reason: to make a political argument that would be meaningful to his audience (and acceptable to the authorities). At our great distance, the particulars no longer mean anything, and Shakespeare’s play reads as a case study of a demagogue’s rise to power in a corrupt society—and of the self-loathing that drives the demagogue in the first place. And, if many of the productions I’ve seen are any guide, many directors are inclined to “reach” the audience by transplanting the play to a political context we are more familiar with, whether it’s fascist Italy or an imagined fascist Britain.

But what a production could do—and one that I saw a few years ago tried to do—is recover for a contemporary audience how an audience in Shakespeare’s day would have understood the story being told. That is to say: to recover for the audience a sense of the providential scaffolding that surrounded Shakespeare’s play. He was telling a story not just about how a demagogue rises to power, but a story about how there is a kind of justice in that rise, a sign from God that the polity deserves to be scourged in this fashion. That’s not a message that modern audiences are likely to bring with them into the theater. For that very reason, it’s one that might be useful for them to hear.

It’s a particularly unwelcome lesson for this theatrical moment. The toast of Broadway, after all, is Hamilton, surely the most successful history lesson ever to tread the boards. And it amply deserves its success. But Hamilton achieves its success precisely by collapsing the space between past and present—by helping us see the founding fathers as fundamentally similar to ourselves. Which, in so many ways, they were—and it’s a great civic service to see them so, and not as marble Solons. But they were also different, in deep and fundamental ways. It’s the job of good history to bridge the gap in both directions: by bringing the past to us, but also by bringing us to the past.

As we move further away from mid-century, we’ll discover things in these plays that audiences back then may not have seen. We’ll have productions that show rape as rape, or that help us feel mass hysteria rather than judging it. But we’ll also lose context that we’ll need other productions to help us recover, whether it’s the post-Holocaust terror of the mob that lurks in the background of Miller’s The Crucible, or the climate of sexual secrecy that suffuses so much of Williams. These are things we think we know about, but that with distance we’ve come to judge with easy familiarity. We may have forgotten what it was like when these weren’t ideas to analyze, but simply part of the air one breathed.

Theater is about the present experience. If the once-recent past is, increasingly, a foreign country, then it won’t be enough for the theater to help us see ourselves among those foreigners, and feel compassion for them as such. It will also have to help us feel how different they were from us—and learn the things they knew that we have forgotten.