“Our writing instruments are also working on our thoughts.” Nietzsche wrote, or more precisely typed, this sentence on a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, a wondrous strange contraption that looks a little like a koosh ball cast in brass and studded with typewriter keys. Depressing a key plunged a lever with the typeface downward onto the paper clutched in the underbelly.

It’s well-known that Nietzsche acquired the Writing Ball to compensate for his failing eyesight. Working by touch, he used it to compose terse, aphoristic phrasings exactly like that oft-quoted pronouncement. Our writing instruments, he suggested, are not just conveniences or contrivances for the expression of ideas; they actively shape the limits and expanse of what we have to say. Not only do we write differently with a fountain pen than with a crayon because they each feel different in our hands, we write (and think) different kinds of things.

But what can writing tools and writing machines really tell us about writing? Having just published my book Track Changes on the literary history of word processing, I found such questions were much on my mind. Every interviewer I spoke with wanted to know how computers had changed literary style. Sometimes they meant style for an individual author; sometimes they seemed to want me to pronounce upon the literary establishment (whatever that is) in its entirety.

Style is at once something tangible – built up out of individual words and phrasings, with the academic specialization of stylometry devoted to its study – and elusive, associated with a writer’s “voice” or the unique “feel” of their prose. Doubtless this is why it fascinates us, and why we’re so concerned to know what computers are doing to it. And yet I think the question is misplaced.

Word processing did change the game

We know a lot of things about how computers changed the nature of literary writing: revision, obviously, became easier, and in fact the distinction between revision and composition began to erode entirely. (There are now dedicated writing devices that force you to power through a draft without stopping to revise.)

We also know that word processors found their way into plots and settings, as typewriters had in novels like William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch or Stephen King’s Misery.

And we know that the circumstances of literary production changed: In 1983, as I detailed in my book, John Updike used his typewriter to fire off a note dismissing his secretary because he had just gotten a word processor. A year later Primo Levi wrote to an English friend that he was “in danger of becoming a Mac bore.” When she wrote back that it was merely a “clever new typewriter,” he replied: “It’s a lot more than that! It’s a memory prosthesis, an archive, an unprotesting secretary, a new game each day, as well as a designer, as you will see from the enclosed centipede picture.”

But none of these are really observations about style.

Style is the sum of many different influences – the instrument the author is writing with, to be sure, but also market trends and editorial dictates, what an author is reading that week, his or her emotional state and much else besides. (Nietzsche himself had chosen the word “Gedanke” in his original German – “thoughts” – not anything so particular as style.)

Recently, in fact, two researchers tried to determine whether literary style could be measured based on whether or not writers had been through an MFA program, another deterministic variable seemingly easy enough to isolate. They failed.

Rather than style, the sense of the text

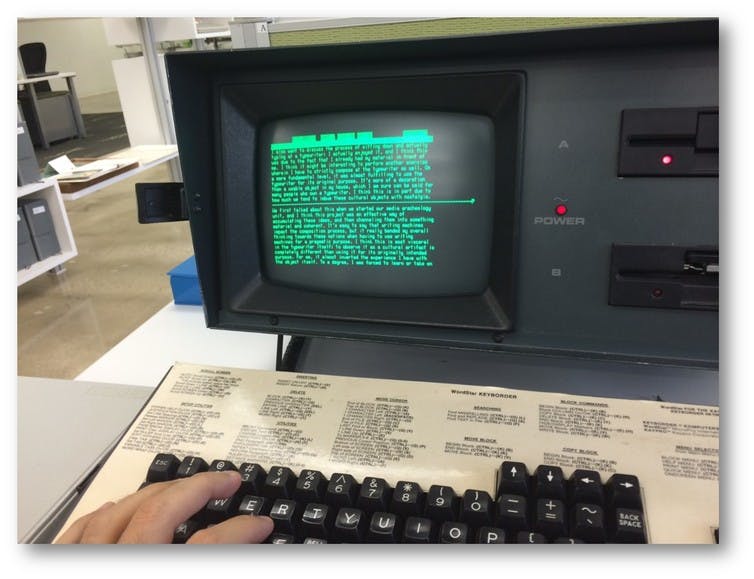

Sitting at a typewriter, we are always in the present moment as the carriage trundles forward character by character, line by line. Word processing, by contrast, allowed writers to grasp a manuscript as a whole, a gestalt. The entire manuscript was instantly available via search functions. Whole passages could be moved at will, and chapters or sections reordered. The textual field became fluid and malleable, a potentially infinite expanse, or at least limited only by the computer’s ever-expanding memory.

The result was a new kind of control over writing space, a sentiment shared by early adopters of the technology otherwise as different from one another as National Book Award winner Stanley Elkin and queen of the vampires Anne Rice. “Once you really get used to a computer and you get used to entering the information from that keyboard, things happen in your mind, I mean, you change as a writer. You’re able to do things that maybe you never would have thought of doing before,” concluded Rice. Elkin extolled his renewed appreciation for plot after acquiring a word processor in 1979: “Plots have become very interesting to me,” he told an interviewer at the time. “You put the machine into the search mode, and you find what the reference was earlier, and you can begin to use these things as tools, or nails, in putting the plot together.”

What Elkin and Rice are describing, each in their own way, is what composition theorists like Christina Haas have called the “sense of the text.” It means the mental model of the words on the page (or screen) and how the writer perceives his or her relationship to them. Word processing, as the testimony of countless writers suggests, profoundly altered their sense of the text, both in terms of how they approached their writing and what they thought possible. But all of that is a far cry from “style,” typically defined as an author’s individual word choices and sentence structures or arrangements.

Running word-processed prose through a computer

Which is not to say that kind of analysis couldn’t be done. In fact, specialists have been doing it for decades. You would begin by choosing a writer like Isaac Asimov, someone who wrote a lot and for whom we happen to know the exact day on which he acquired his first computer: a TRS-80 Model II on May 6, 1981. You would want a digitized corpus of his books from before and after, and then you would see what you could find with your algorithms.

Even then, though, the question would nag: What would those algorithms tell you? They might reveal some heretofore unimagined master key to Asimov’s oeuvre. But you might also be left with something like stylometrist Louis Milic’s contention about Jonathan Swift, famously demolished by literary theorist Stanley Fish: “The low frequency of initial determiners, taken together with the high frequency of initial connectives, makes [Swift] a writer who likes transitions and made much of connectives.”

As it happens, a couple of researchers a few years back performed exactly this exercise with Nietzsche; tantalizingly, they were apparently able to distinguish between his earlier and later style, pivoting around the onset of his blindness and the acquisition of the Writing Ball. Their results were based on word frequencies, an analysis of which showed the philosopher’s writings to cluster into different groupings based on dates in which the texts were composed.

And yet, a table of word frequencies has nothing to do with sentence length, which was the impetus for the philosopher’s own comment in the first place. Nietzsche, after all, was remarking on the way in which the Malling-Hansen lent itself to brief bursts of text (not unlike tweets) – not the evolution of his personal vocabulary. And we also know that the Writing Ball was only one of several workarounds Nietzsche was eventually forced to adopt – he also dictated prose aloud to secretaries, for example.

Anne Fadiman once claimed she could detect the “spoor” of word processing in other writers’ prose. Using computers to sniff out other computers may yet tell us fascinating things about the delicate membrane between thoughts and the written word. Indeed, it may be that the best way to measure the technology’s impact on literary style is in aggregate, through big data approaches: assembling dozens or hundreds of authors’ bodies of work. It would be fascinating to know, for example, whether the dictates of the grammar checkers built into modern word processors have had a measurable impact on literary prose.

But we’ll still be left with all the imponderables of hands on keyboards. Writing machines may be complicated, but writing itself is always infinitely more so.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.