What is Ruth Bader Ginsburg thinking?!

This is the essential question underlying nearly every news article and cable segment about the 83-year-old Supreme Court justice’s decision to campaign against Donald Trump. Last week, she told the Associated Press that she doesn’t want to think about the possibility of a Trump presidency. In a New York Times article published Sunday, she said she “can’t imagine what the country would be — with Donald Trump as our president” and implied she would move to New Zealand if it happened. And on Monday, in an interview with CNN, she called Trump a “faker” who “really has an ego.”

Ginsburg is the only sitting justice with a fanbase. That fanbase developed organically, but she has courted it and encouraged its growth. Notably, its members are the only ones who are unquestioningly enthusiastic about her criticism of the presumptive Republican nominee. Ginsburg has her reflexive detractors, too, including Trump.

Justice Ginsburg of the U.S. Supreme Court has embarrassed all by making very dumb political statements about me. Her mind is shot - resign!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 13, 2016

Between those poles, the debate spans the fairly narrow gamut between whether her comments were wholly inappropriate or merely unwise, with a few contrarians arguing that her politicking is either harmless or might actually be good. Many people in the former camp agree with the content of her Trump critique—he is a dangerous “faker,” after all—but believe Supreme Court justices should never violate the norms that are meant to wall them off from politics.

This is where I landed on the question instinctually. But the controversy now strikes me as much ado about less and less. The overriding concerns about Ginsburg’s comments reflect admirably cautious instincts: The judiciary should be above politics; justices should not be political operators; they should be people of guarded temperament, not crowd-pleasers; we should not welcome or be blasé about the slippage of governing norms.

If you share those instincts, then at first blush Ginsburg’s behavior seems indefensible. But days later, her behavior strikes me as slightly ill-advised rather than outrageous. Viewing her decision in a vacuum distorts the question at stake, and is less illuminating than viewing it in context: Is the ideal of a depoliticized judiciary achievable? Did Ginsburg take us farther away from it? If so, was hers a reckless decision that will change the character of the Court forever, or a judicious one that will have few if any consequences?

The answers don’t necessarily vindicate Ginsburg, but they do show that the fainting-couch routine we’ve witnessed over the past several days is unnecessarily melodramatic. It’s a much closer call than any black-and-white conclusions suggest.

It’s tempting to consider Ginsburg’s comments in isolation and adjudicate them based on the simple heuristic that if the parties were reversed—if an iconic conservative justice were criticizing a Democratic Party nominee—Ginsburg’s allies would be furious and some of the conservatives who are attacking her now would be making excuses for “their” justice. If that’s true, the thinking goes, then there’s no principled basis for excusing Ginsburg.

But that’s the wrong analytical starting point, and, critically, it’s a form of question-begging. The fact that partisans behave in unprincipled fashion doesn’t have any bearing on the underlying concern about whether justices criticizing political candidates is actually dangerous, or whether Ginsburg’s actions fit neatly within that general description.

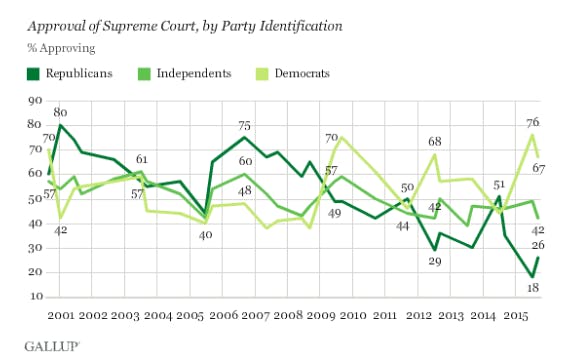

A better starting point is to acknowledge that the modern judiciary has never resembled its idealized form. Though no justices have campaigned against a presidential candidate in recent memory, some have behaved in brazenly political ways. This, significantly, has had little bearing on how the public views the Court. Public opinion of the court appears fairly stable, but is actually extremely volatile, when broken down by partisan affiliation. It soars among Democrats and plummets among Republicans when, say, Obamacare survives, and vice versa when, say, the Court hands the presidency to George W. Bush after he lost the popular vote and was on his way to losing the recount in Florida.

Whether you believed these decisions were principled or defensible or not, there’s very little basis to believe the public sees the court as anything other than a political agent. It’s good when it does politically desirable things and bad when it doesn’t. To assume that partisan actions by Supreme Court justices are bad because they erode public faith in the institution misunderstands what public faith in the Court really means. The idea that the public sees the court as independent from politics is pure fantasy.

That, again, doesn’t excuse Ginsburg. But it clarifies and reduces the stakes of her comments.

Of course, the fact that the Court has never functioned ideally, maybe never will, and that the public doesn’t particularly want it to, doesn’t mean we should celebrate further erosion of the ideals themselves. But do Ginsburg’s actions actually constitute erosion? That isn’t as clear as many assumed when they formed their initial conclusions about her this week.

Whatever veneer of judicial impartiality existed before this week was already very thin. It’s not as if we didn’t have a good sense of Ginsburg’s views about Trump before she expressed them out loud, and it’s not as if Justice Antonin Scalia took his completely mysterious views about President Barack Obama to the grave. So if a new line was crossed, it was fairly close to the old line. Almost exactly four years ago, from the bench of the Supreme Court itself, Scalia opined in very critical terms on Obama’s deportation relief program for Dreamers, in a case that was argued before the Court months before the program, called DACA, was announced.

Perhaps criticizing the president’s policies in ways that could easily be used in campaign ads is different in degree from the criticisms Ginsburg directed at Trump. But these adjacent lines are starting to blur. That Scalia did a controversial thing doesn’t justify Ginsburg’s doing a different controversial thing; it doesn’t even necessarily justify Ginsburg’s doing the same controversial thing. But it does call into question whether the hyperventilating over her breach of protocol is commensurate with the facts at hand.

The counterpoint is that Ginsburg may have set a precedent that we will regret, should justices start freely commenting on campaign politics, and the Court accelerate down the path toward becoming a super-legislature. Ginsburg may have only turned a very pronounced subtext into actual text, but that doesn’t make it a trivial matter. A major basis of the backlash to Trump is that turning subtext into text can amount to a radical departure from important norms.

But context matters here, too. Is a Supreme Court justice obligated to remain in the realm of subtext no matter how great she imagines the danger facing the country to be? What if a presidential candidate is campaigning on a promise to ignore congressional and judicial limits on his power, and she is planning to retire no matter who wins the election? Or what if there is a significant bipartisan and cross-ideological consensus that the candidate is a dangerous threat to our democracy?

Well, here we are: a situation none of the justices has encountered before and hopefully won’t encounter again. If Marco Rubio had become the GOP’s nominee and Ginsburg said the same things, the new precedent would be obvious and unfortunate, and there might be no going back.

But extraordinary circumstances can limit the reach of new precedents, and Ginsburg has the wisdom and breadth of experience to make us question our reflexive sense that we understand governing norms better than she does.

Vox’s Matt Yglesias looks at Ginsburg’s comments and sees “the risks of becoming a viral sensation late in life.” I see a woman who endured incredible sexism well into her professional career, warning the public about a politician whose sexism would make Don Draper uncomfortable, and who promises to restore a more patriarchal order. I see a Jewish woman with living memory of the Holocaust who is more likely reacting to the normalization of neo-Nazi propaganda than pandering to Notorious RBG readers.

New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait argues that “there is a lot of ground between a world where justices indicate their partisan leanings in private settings and a world in which Republican nominee Ted Cruz is clasping hands on stage in Columbus, Ohio, with Samuel Alito on election night, 2020.” This is true. But he adds that “Ginsburg has covered a good deal” of that ground. Not only is this not true, he’s also glossing over his own conclusion that Trump represents a break in the continuum between George W. Bush and Ted Cruz: “An unprecedented threat to our democracy.” Ginsburg appears to be affirming this conclusion and responding to it in her own considered way.

Apolitical officials make these judgment calls from time to time. When FBI Director James Comey testified before Congress last week about his unprecedented decision to announce the findings of his investigation into Hillary Clinton’s handling of classified information—a presentation normally reserved for a prosecutor issuing an indictment, rather than an investigator recommending against one—his explanation was eminently sensible.

“I [decided] I would do something unprecedented because I think it’s an unprecedented situation,” he told the panel. “Now, the next director who is criminally investigating one of the two candidates for president may find him or herself bound by my precedent? OK, if that happens in the next 100 years, they will have to deal with what I did. I decided it was worth doing.”

Likewise, if the precedent Ginsburg set means that in the next 100 years, a sitting Supreme Court justice feels bound or empowered to speak out about the rare dangers of one of the two candidates for president, this is something we can live with. If Alito endorses Cruz in four years, he will be doing something altogether different.

Even after taking all this into account, I still think Ginsburg made an error, if not of precedent then of strategy. Why risk any repercussions when more public-facing, publicly accountable institutions seem to be containing the Trump threat fairly well? But those asking “What is Ruth Bader Ginsburg thinking?!” should make a good-faith effort to consider her decision from her perspective. They’ll find the uncomprehending tone of their question says more about them than it does about her.