Veepstakes speculation is rampant as we approach the national conventions for both major political parties.

Media reports have detailed the wide array of options available to Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton as they decide who will be their number twos for this campaign, and perhaps for four or eight years to come.

Who will Trump and Clinton pick? That depends on each candidate’s goals – both for the remainder of the presidential campaign and after Nov. 8. Political observers widely agree that the most important characteristic to look for in a running mate is the ability to serve as president in the event of unforeseen circumstances, like a president’s death, incapacitation, resignation or impeachment.

However, when campaign staff and trusted political advisers vet potential running mates, they are certain to also weigh political considerations. That is, whether a given running mate will help or hurt the presidential ticket, with voters in general or with a key voting group. Particularly if the campaign is at a competitive disadvantage, its strategists may look to the running mate as a potential “game changer.”

The electoral advantage most commonly associated with vice presidential candidates is geographic. In other words, they are expected to deliver their home state or region in the Electoral College. But do they actually deliver?

Usually not.

In our book, The VP Advantage: How Running Mates Influence Home State Voting in Presidential Elections, we employed a multi-method approach to empirically test the purported home state advantage. We used both state-level election returns since 1884 and individual-level survey data since 1952 in our analysis. Ultimately, we found no evidence of a general vice presidential home state advantage, on average.

Based upon the data, it is unlikely that Hillary Clinton’s or Donald Trump’s running mate will deliver a crucial battleground state, like Ohio or Virginia. Instead, the presidential candidates would be wise to select a respected running mate who can effectively serve as vice president.

Mythbusting: VP influence

Survey data and internal campaign polls from 1960 even cast serious doubt on the “fact” that Lyndon Johnson delivered Texas and the South for Democratic presidential candidate John Kennedy that year. Although presidential candidates typically receive an electoral advantage in their home state, our findings for vice presidential candidates suggest a conditional relationship.

Such advantages are most likely to occur in less populous states where a running mate has significant elected political experience within that state. The vice presidential candidacies of Maine’s Edmund Muskie (1968) and Delaware’s Joe Biden (2008, 2012), both political “institutions” in their small home states, serve as perfect examples.

How about demographic appeal, then? Will a running mate deliver votes from a targeted demographic group — say, based on gender or religion — if she also belongs to that group? To find out, in a recent analysis we tested whether women (1984 and 2008), Catholic (1972, 1984, 2008, and 2012), and Jewish (2000) voters were more likely to vote for a presidential ticket that included a vice president from the same demographic group. Once again, running mates failed to deliver as expected.

True, voters more positively evaluated vice presidential candidates who belonged to their demographic group. But this did not change votes. Women, for instance, were no more likely than in other years to vote for a ticket featuring a woman as running mate, and the same generally goes for religious minorities.

While there’s a great deal of speculation that Hillary Clinton will select a Hispanic running mate, partly in hopes of increasing her vote share among Hispanics, this evidence suggests that she should not expect such an advantage. Of course, she may perform better among Hispanics for other reasons, namely opposition to Donald Trump’s candidacy.

Do VP’s even matter?

So, are vice presidential candidates electorally irrelevant? No, far from it.

Campaigns could use a running mate as a means to reinforce a campaign theme or foster party unity. Ted Cruz selecting Carly Fiorina as his seven-day running mate, for example, reinforced Cruz’s campaign brand of a political outsider who would shake up Washington.

In 1976, Ronald Reagan used his vice presidential pick to attempt to unify the warring factions of his party and pick up uncommitted delegates at the Republican National Convention. It backfired when he announced Sen. Richard Schweiker of Pennsylvania would be his running mate, which provoked a strong reaction from Sen. Jesse Helms and other conservatives. Gerald Ford got the nomination that year.

Four years later, Reagan considered the possibility of inviting Ford back to the ticket as his running mate in what some dubbed a co-presidency. Instead he offered the vice presidential slot to his relatively moderate primary opponent, George H.W. Bush.

Indeed, the empirical evidence suggests that running mates have a modest, but measurable influence on presidential vote choice. In our book, we used data from the American National Election Studies and found that evaluations of presidential candidates are three times more influential than evaluations of running mates, when explaining voter choice.

Remember, voters must choose between presidential tickets, and not just presidential candidates. That’s why VP candidates have some level of influence on voters, albeit small relative to the presidential candidates. This means a vice presidential candidate may strengthen or weaken overall evaluations of the ticket to the extent that he or she is very appealing or very unappealing to voters.

The major takeaway from our findings is this: If a running mate is exceedingly popular or unpopular relative to the presidential candidate, then they could marginally influence vote choice at a national level.

Typically, this does not happen. When vetting running mates, most campaigns take a “do no harm” approach and ensure that the vice presidential pick will not detract from the presidential candidate. Most vice presidential candidates are not exceptionally popular or unpopular. Many are simply unknown to voters.

Of course, there are exceptions. For example, political science research has estimated that Sarah Palin may have cost John McCain as many as 2.1 million votes in 2008 due to her unpopularity among moderate voters. At the same time, however, Palin energized the conservative base and motivated some voters to support McCain who otherwise would have stayed home on Election Day.

Setting expectations for 2016

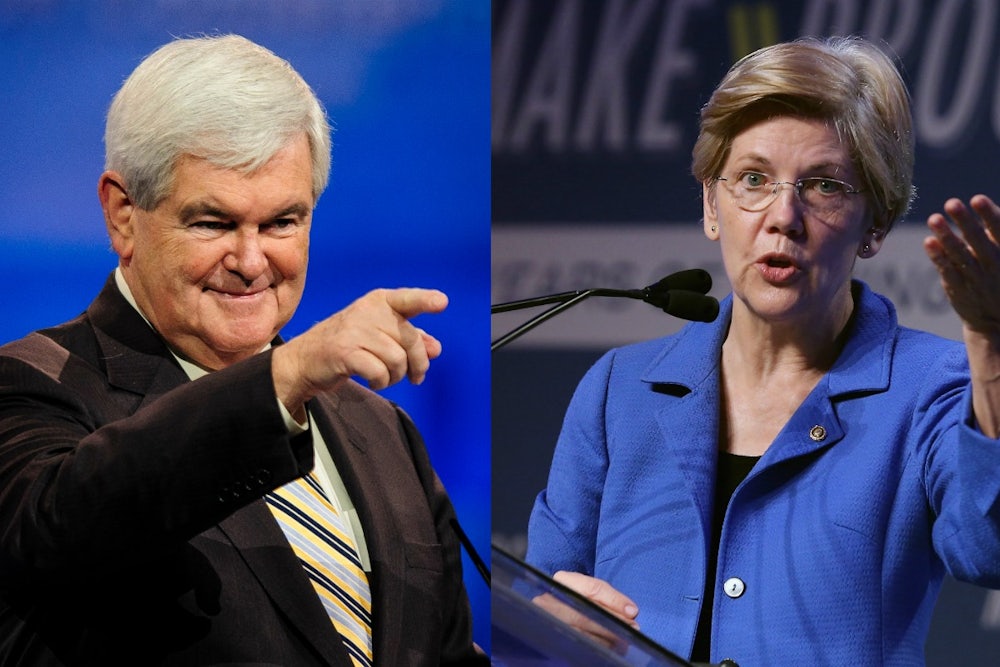

What does all of this mean for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump in 2016? Given that both candidates have historically high unfavorable ratings after winning exceptionally divisive party nomination campaigns, a vice presidential candidate could influence voters more in 2016 than in a typical election year.

If Clinton or Trump select a running mate who is also unpopular, while the other selects one with high or even neutral favorability among voters, the latter could make a positive and meaningful contribution to the overall ticket.

Perhaps, then, this is the year that vice presidential selections will make a difference — not by delivering a key state or voting bloc, but by enhancing the popularity of a presidential ticket that desperately needs the help.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.