A number of developments over the course of the past year have helped contextualize this unusual, at times surreal, American election season. Events like the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, the rise of the police protest movement here in the United States, and the white backlash to it, have been powerful reminders that racial tribalism is the great political fault line in the Western world dividing whites from minorities, the old from the young, the urban from the rural.

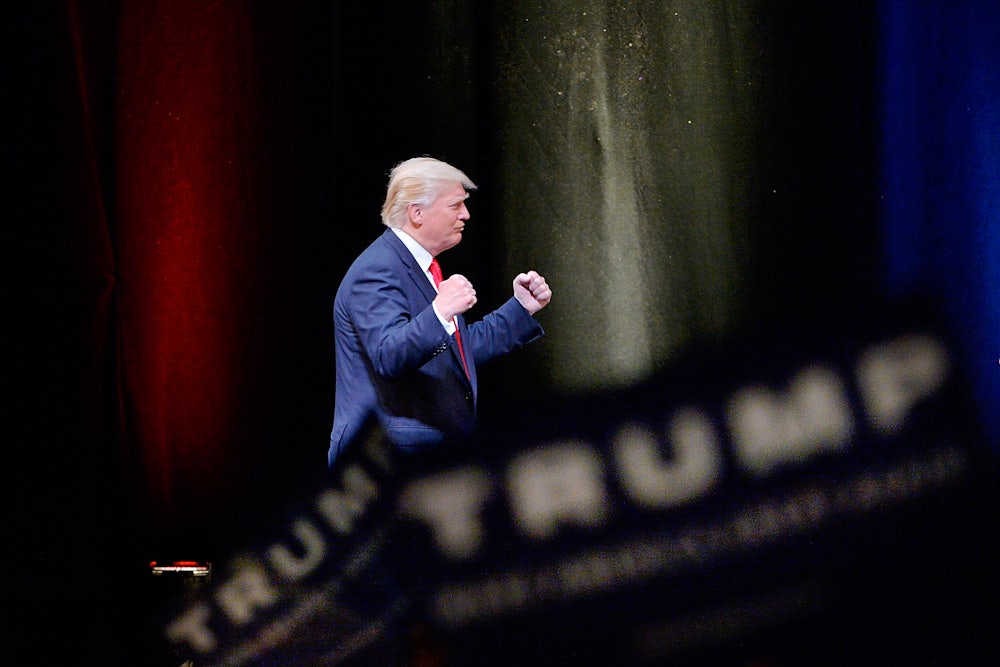

If making sense of Donald Trump requires regular reminders that he is an outgrowth of powerful, ingrained political forces, rather than an unfortunate aberration, the world is certainly obliging. He is the patron saint of resentful whites, who are in turn the dominant faction of the Republican Party. But these reminders provide little information about how the American political economy should be reordered to meet the needs of both white nativists and ethnically diverse liberals.

In a country divided such as ours is, an election can help break impasses by providing reasonably clear guidance on what changes the majority of people want to make. But the strangeness of Trump’s campaign is sidelining that guidance. Rather than serving as an exponent of white working-class interests, advancing a policy agenda that would materially benefit his supporters, Trump serves merely as their id.

This has made collateral damage out of ideology. Not since 2000 has a U.S. election been so untethered from substantive questions about how to make people more satisfied with the ways the government serves them. Trump has made this election a referendum on our national identity—are we the kind of country that turns to a demagogue when enough people are frustrated?—rather than on our policy status quo. Once that identity issue is resolved, the question of what comes next won’t have a clear answer.

Even a happy ending to this election—a Trump defeat—will leave our governing institutions paralyzed or powerless to respond to the signals voters will have sent. If the public is already worryingly disaffected by gridlock and dysfunction in government, this election promises to worsen the trend.

It’s worth reflecting on how unusual this situation is. After 2000, the country held a referendum in 2004 on George W. Bush’s decision to invade Iraq and his management of that defining misadventure. He survived that referendum. In 2008, after voters had awakened to the comprehensive failure of Bush’s administration, they turned to someone who promised to govern the country in almost the opposite fashion. Barack Obama was deliberative where Bush was reactive, cerebral where Bush was not, dovish where Bush was hawkish, liberal where Bush was conservative. Obama promised to draw down Bush’s war in Iraq, reverse Bush’s tax cuts for high earners, create a national health care system, implement a program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and avert the worst consequences of climate change. Upon taking office, Obama began pursuing all of those objectives.

Four years ago, amid a tepid recovery from the economic crisis Bush handed off to Obama, Republicans asked voters to embrace the conservative movement’s vision of a radically retrenched government. Obama asked them to preserve the basic social compact that has prevailed in the country since the 1960s, and to let him continue building upon it. Forward, not backward. He won, and cemented much of his agenda.

If Marco Rubio or a more orthodox Republican had beaten Trump this year for the GOP nomination, this election would be reduced to similar questions, only with Hillary Clinton viewed as a virtual incumbent and agent from the past, and the radical ends of movement conservatism presented as a plausible alternative for the future. Clinton’s childcare and student loan plans would have been held up against the GOP agenda as a continuation of Obamaism, and the country would have decided which vision they preferred.

But Trump has completely upended the platonic notion of elections as tools to settle public policy debates. His agenda, such as it is, either can’t or won’t be implemented, even if he wins. Mexico is not going to pay for a wall along the border, and the U.S. government is not going to expel 11 million unauthorized immigrants, much less ban Muslims from entering the country. It is altogether more likely that were he to win, the movement conservatives who still control Congress would present him the kind of plutocrat-friendly legislation that alienated their voters and drove them to Trump in the first place. His supporters would be rewarded for their triumph with a vision of change they don’t share and didn’t vote for.

In the likelier event that Clinton wins, but does not secure majorities in both the House and Senate, the public will have rejected Trump’s ugly vision of a resentful, bigoted America, but will not see that verdict translated into any policy changes that reflect Clinton’s vision of a more inclusive, cosmopolitan society.

At a time when trust in government is at a historic low, this is a worrying outlook. One of the key feedback mechanisms of our democracy has been malfunctioning for many years now. Next year it is likely to fail altogether.