From day two, or so, of President Obama’s first term in the White House, Democrats were pretty sure that he’d be running for re-election against Mitt Romney.

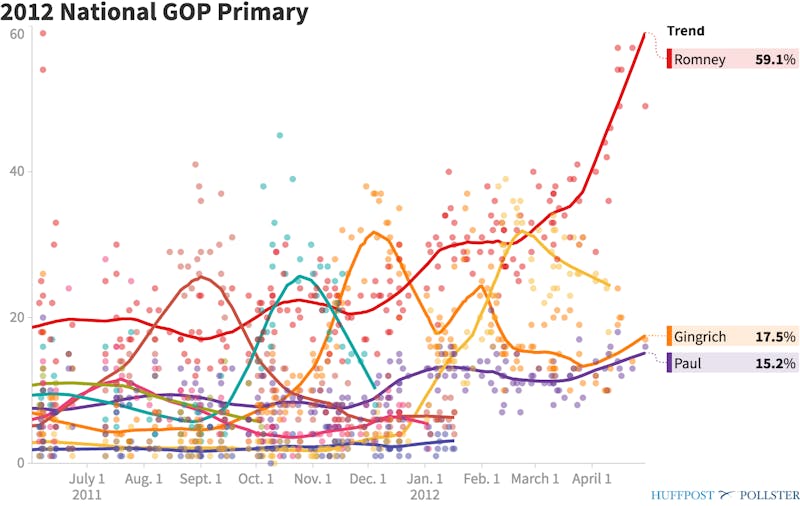

Three short years later, Romney was indeed still the frontrunner for the Republican Party’s 2012 presidential nomination, but he was having a hard time sealing the deal with conservative GOP primary voters. At various intervals, random dark horses would shoot ahead of Romney in polls, only to fall back out of contention:

As you can see from this chart, the last one to really threaten Romney before voting began, and the only one who had a second, smaller surge—before Romney’s Super PAC clobbered him—was Newt Gingrich.

The thought that they had been wrong all along, and that they might end up running against Newt instead of Romney, left Democrats absolutely beside themselves. As it happened, I interviewed House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi in December 2011 just as Gingrich was reaching peak strength. She seemed to struggle with the tension between her giddiness at the thought of taking on the former speaker, and her strategic intuition that she could hurt Gingrich’s chances by divulging damaging information about him.

“I like Barney Frank’s quote the best, where he said, ‘I never thought I’d live such a good life that I would see Newt Gingrich be the nominee of the Republican party,’” she told me. “That quote I think spoke for a lot of us.”

Then her game face slipped, and she let it be known that she knew more damning information about Newt than almost anyone working in politics. “One of these days we’ll have a conversation about Newt Gingrich,” Pelosi added. “I know a lot about him. I served on the investigative committee that investigated him, four of us locked in a room in an undisclosed location for a year. A thousand pages of his stuff.”

When I asked for a preview, she returned to equipoise. “Not right here. When the time’s right.”

Gingrich, for his part, pretended to be thrilled Pelosi had told the world she had a lot of dirt on him. But his moment quickly passed, and the right time for Pelosi to open up her mental oppo file never came.

All this background is newly relevant now that Gingrich is reportedly on Donald Trump’s vice-presidential shortlist, and is auditioning for the role at a rally outside Cincinnati Wednesday evening. The point is this: Before Trump came along, Democrats couldn’t imagine an easier candidate to beat than Newt, and now it looks like they may get to run against both at once.

There are other candidates reportedly under consideration, including the comparably toxic Chris Christie, and the steadier-handed Governor Mike Pence of Indiana, who has criticized Trump. Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee—who called Trump’s reaction to the Orlando massacre “very disappointing,” and said that his racist attack on Judge Gonzalo Curiel was wrong “on every level”—was also on the list, but withdrew of his own volition after Trump once again praised Saddam Hussein’s habit of murdering suspected terrorists without due process. (Joni Ernst, the first-term senator from Iowa who Trump had reportedly considered, also said today that she plans to stay put in the Senate.)

Corker’s departure epitomizes Trump’s conundrum. For a campaign struggling as badly as Trump’s is, and for a candidate with Trump’s liabilities, the ideal running mate is someone who has governing experience, and can be sold to the doubtful as a ballast to Trump’s wayward leadership. Someone like Corker or Pence, in other words, rather than someone like Gingrich who compounds Trump’s worst problems (brash, philandering, erratic, etc.). But it isn’t clear that anyone of stature in the GOP would take the job. If it were, Gingrich probably wouldn’t be anywhere near the short list, and Corker wouldn’t have taken himself off of it.

Republicans like Corker, with bright futures and wide respect within the party, have kept a greater distance from Trump than those who are damaged goods or whose careers have reached dead ends. That has inverted the calculation that typically governs the VP-selection process. Normally, a major party’s presidential nominee gets to choose among the best his or her party has to offer, and looks to someone who can help the campaign, the party, and the prospective administration in some meaningful way.

The multi-part question here, by contrast, is: Can anyone who isn’t already debased by association with Trump run with him without becoming similarly debased? Would anyone in that position agree to do so? And would Trump be willing to go the distance with a running mate who hasn’t already joined the campaign enthusiastically?

Of course, a vice presidential nominee will become colored inevitably by the public’s perception of the person leading the ticket, and that goes double for the unfortunate soul running with Trump, who leaves an unusually potent residue. If Gingrich has any hope at all of becoming the GOP’s vice presidential nominee, it’s because few people of any merit would be willing to run with Trump, and Trump would be reluctant to run with anyone who didn’t hop aboard the Trump Train early on.

That’s the basic dynamic that makes Gingrich a contender. Under the circumstances, Trump might consider sweetening the deal for a reluctant but better-composed running mate by drawing on his vast fortune and offering up a bribe.