Appearing on NBC’s Meet the Press on Sunday, Virginia Senator Tim Kaine told Chuck Todd his best dad joke. “I’m boring,” he said. “But boring is the fastest growing demographic in the country.”

Kaine’s 15-minute appearance on the show served as supporting evidence. He didn’t take pot shots or offer Twitter-friendly quips. Instead, he mostly played nice. When Trump came up, he suggested the real estate magnate was a narcissist—and then quickly backed off. “We are not enemies, but friends,” he said, quoting Lincoln’s first inaugural address. “We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection.” (The Civil War began five weeks after Lincoln made those remarks.)

Kaine is self-aware: He is boring, though not necessarily Ambien personified. He’s affable, often grins when he speaks, and has an inviting, slightly Midwestern lilt, despite being a lifelong resident of Virginia. He mostly comes across as a corny uncle, a guy who wears a “Hot Stuff Coming Through” apron while he’s grilling. Instead, Kaine is boring from an ideological perspective: He’s a “party guy,” to use Reince Preibus’s term, a pragmatist with an ear for compromise and an aversion to rocking the boat. He has a reputation for supporting prudent, clear-eyed policies on contentious issues like gun control and the death penalty. In the rare instance where he diverges from orthodoxy—his opposition to abortion—he insists his disagreement is merely personal and supports the policy anyway.

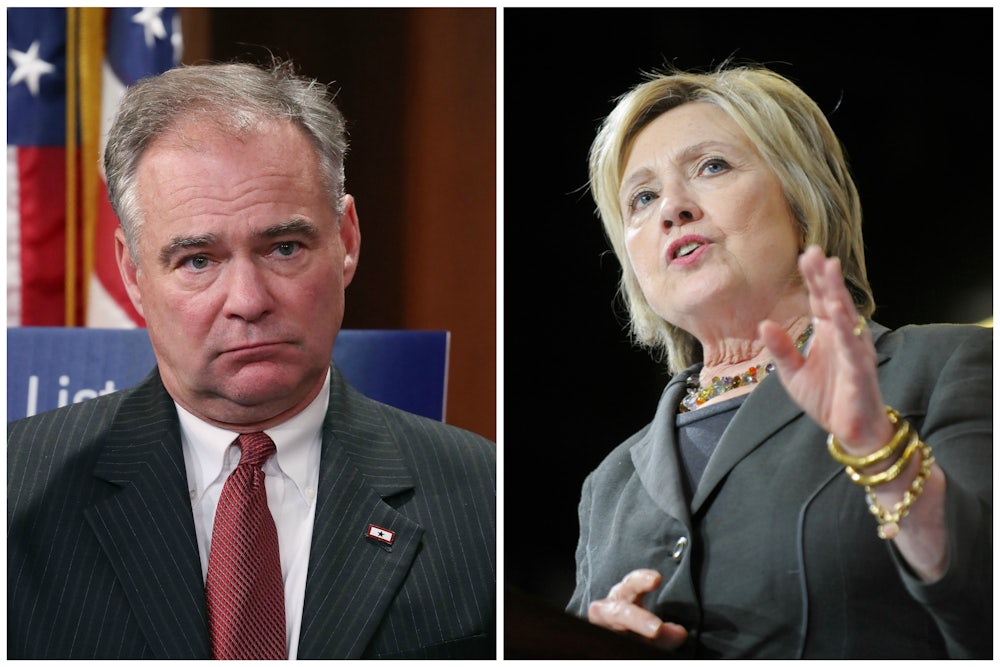

Kaine’s caution has endeared him to Hillary Clinton, a candidate whose defining trait is just that. So it’s no surprise that he’s seen by many as the frontrunner to be her vice president. He “towers” over the other candidates, if Politico, which has devoted two pieces in the past week to his frontrunner status, is to be believed. And in recent weeks, everyone from The Washington Post to CNN to NBC to the National Review has listed Kaine as Clinton’s likeliest running mate.

But if Clinton wins, the country will already have a boring president; it doesn’t need a boring vice president, too. More importantly, tapping Kaine would play right into Donald Trump’s hands.

Kaine, 58, is supremely qualified to be vice president. Educated at Harvard Law School, he has worked as both a Catholic missionary and a legal advocate for those facing housing discrimination because of their race. He’s been mayor of Richmond, governor of Virginia, and chairman of the DNC. Despite his personal opposition to abortion, he has a 100 percent rating from Planned Parenthood. He’s also fluent in Spanish: In 2013, he supported the Gang of Eight immigration reform bill by delivering, for the first time in this country’s history, a speech on the Senate floor entirely in Spanish. He’s critical of the expansion of executive power, especially when it comes to armed conflict, but has a knack for constructive, bipartisan criticism: In 2014, he co-sponsored a bill with Senator John McCain that aimed to amend the War Powers Act of 1973 to restrict the president’s ability to conduct war unilaterally—something that might not endear him to Clinton. (Kaine also has a gift for picking winners early: He endorsed Obama in February of 2007, and endorsed Clinton two years ago.)

So Kaine’s experience is on par with, or even exceeds, Clinton’s. But there are a number of competing theories about how to pick the best running mate. A vice president can be selected to complement the nominee by covering for her perceived weaknesses—think Joe Biden, whose foreign policy experience shored up Obama’s lack thereof—or simply to support the nominee as a partner in governance. In other instances, a nominee is chosen to excite an apathetic base (Sarah Palin in 2008 is the most infamous instance) or for demographic reasons: Bill Clinton’s selection of fellow-southerner Al Gore in 1992 signaled that the Democrats were going to fight for votes in the region. No matter the strategy, though, the prevailing wisdom is “First, do no harm”: choose a vice presidential candidate who, at the very least, won’t noticeably impact the nominee’s poll numbers. In that regard, Kaine may be the safest potential pick.

But as with sports cars, the safest choice in politics isn’t always the best one. Kaine has little upside. In 2008, when he was also considered a frontrunner for the position, Politico said he could serve as an ambassador to “Virginians, Catholics, working-class white voters and Hispanics.” Let’s take these one at a time: Clinton has a strong chance of winning the state regardless of her running mate. The Catholic vote doesn’t win elections. He likely appeals to non-college-educated white men more than Clinton does, but Trump owns that demographic anyway. And his Spanish skills may appeal to Hispanics, but not nearly as much as a Hispanic candidate would. Kaine doesn’t appeal to a substantial demographic group that Clinton doesn’t already have in her pocket, and he does nothing to win over moderate Republicans that Clinton doesn’t do already; Kaine is Clintonian in his desire to work with Republicans to achieve consensus-based compromise legislation, something that occasionally frustrated those around him early in his career. He’s a longtime party insider and cautious centrist who won’t appeal to Bernie Sanders’ supporters who are skeptical of the Democratic Party’s leadership and its relationship to Wall Street. (He’s repeatedly Wall Street’s preferred veep candidate.)

Choosing Kaine would effectively double-down on Clinton’s core argument that she represents order and Trump represents chaos—that is, experience and inexperience, respectively. But she doesn’t need to double-down on it since Trump unwittingly makes the case himself, over and over again. Kaine is too similar to Clinton in damaging ways: They’re both pragmatic centrists, party insiders, and longtime inhabitants of the Beltway establishment. Choosing Kaine would further expose Clinton to attacks that she represents a corrupt political structure that has enriched itself at the expense of ordinary Americans. “The people who rigged the system are supporting Hillary Clinton because they know as long as she is in charge nothing will ever change,” Trump said on Tuesday, while standing in front of a wall of crushed plastic bottles.

He could add “and Tim Kaine” to that attack line and no one would bat an eye.

Could the selection of a mainstream, moderate Democrat make an electoral difference for Clinton? Perhaps, if she had a realistic shot of winning over more than a handful of moderate, disillusioned Republicans. But the Republican electorate has few George Wills in its midst: there is growing evidence that, whatever his electoral troubles, Donald Trump has solidified Republican support after winning the nomination. As of early June, Trump’s “share of the Republican vote at this point in the campaign is right in line with past nominees,” according to FiveThirtyEight. And anyway, growing political polarization has made reaching across the aisle, especially in a presidential election, less of a winning electoral strategy—there are simply fewer leaning Republicans to win over.

That polarization only makes winning over Democratic voters, particularly those who supported Sanders, more important. The days of Clinton needing to down shots of whiskey to win over voters are finished. She can afford to select a running mate outside of the safe, moderate, old-fashioned Democrat mold, and there are two big reasons why she needs to.

First, Clinton needs to animate the base, as she will probably lose if turnout is remarkably low. Kaine does nothing to energize younger voters or Sanders supporters (who are younger voters). Firebrand Senator Elizabeth Warren and suave HUD Secretary Julian Castro, two charismatic and electric campaigners who are also on Clinton’s shortlist, both do. They also represent, in different ways, the future of the party: demographically in Castro’s case, and ideologically in Warren’s.

Second, defeating Trump will require taking him down on the campaign trail. Kaine has a deft touch, and is especially good at making subtle and intelligent arguments when attacked: When challenged on his faith-based opposition to the death penalty when running for governor—attack ads were run suggesting he would not have killed Hitler, if given the opportunity—Kaine argued that his faith also meant he would enforce the law of the land. (Kaine oversaw eleven executions as governor.) But Trump is an opponent who requires a flame-thrower, not a scalpel, to be defeated. Clinton’s campaign has been at its best when she’s on offense—hitting Trump’s incoherent and dangerous foreign policy. Clinton needs to surround herself with those who can go on the attack consistently, something Warren has proven adept at in recent weeks. (Warren has the added bonus, as The New Republic’s Brian Beutler pointed out, of having a particular knack for getting under Trump’s skin.)

Trump may be lagging behind Clinton in the polls, but he’s closed the gap in recent days and the conventions have yet to come. This is Clinton’s race to lose, but that doesn’t mean she can afford to play a prevent defense. Kaine may be the do-no-harm candidate, but her failure to pick a more dynamic politician—one that complements rather than mirrors her—would do plenty of harm indeed.