On a ramshackle industrial block in southern Brooklyn, an Arabic call to prayer can be heard over the humming traffic of the nearby Belt Parkway. The sound rises from Bay Ridge’s Beit Al-Maqdis mosque, a white-and-green building whose stubby minaret barely crests the high walls of abutting warehouses. From the outside, the house of prayer looks moderately reverent, but on the inside its linoleum floors and poster-pasted walls are more reminiscent of a school cafeteria. On weekdays, between fajr and dhuhr prayers, the drafty main hall grows raucous as dozens of women in black abayas and colored hijabs arrive in waves of banter and warm greetings. They split into groups, squeezing into desks designed for children, arraying purses and plastic bags around their feet. Between each “classroom” are flimsy room dividers that give some semblance of order, but they do little to corral the breathless chatter of the 50-plus students and volunteers.

At one end, ten women in a lopsided circle face their teacher, Stephanie Boyle, who on this day is dressed in a tracksuit, her dark hair pulled like an exclamation point atop her head. Boyle, a professor of history at New York City College of Technology, moves with a martial gait around the circle, warming up her students with a few brisk greetings. Her expression is cheerful, but her squared shoulders match the crisp urgency of her voice as she launches into the day’s lesson: “What are the first three words of the Constitution?” She presents the question to Sutrallah, a middle-aged Yemeni mother of seven whose fingers knot nervously in her lap.

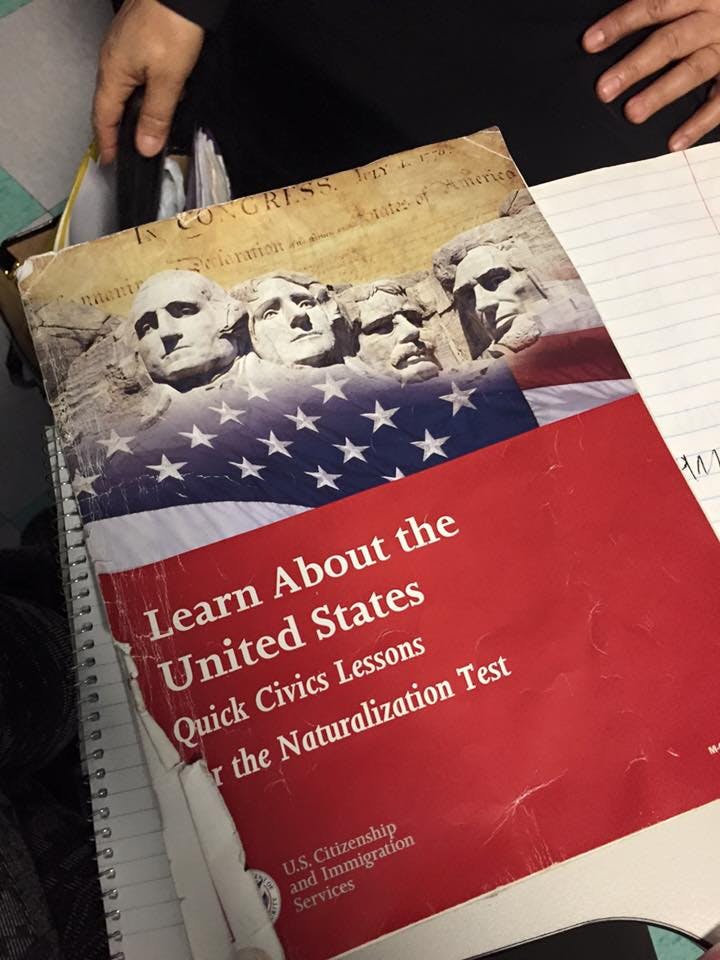

Most of the classes at Beit Al-Maqdis teach English, but on Fridays Boyle and her students gather for another purpose: to prepare for the U.S. Naturalization Test. Boyle’s students are all Green Card holders with aspirations of becoming American citizens, and the test, comprised of reading, writing, and oral examinations, is the bar they must clear to achieve this. The group works from a study guide that lists the exam questions—all 100 of them—alongside the answers. Two weeks into the class cycle, and they’ve made it to question number three. On paper, the full question reads:

The idea of self government is in the first three words of the Constitution. What are these words?

In several months of teaching, Boyle has yet to have a student pass the exam, although a few have tried. Among those who have gambled the $680 application fee is Aisha, an 81-year-old Moroccan widow who speaks of the experience in soft, slow tones. Although she is fluent in Arabic and French, she struggles with English. “I fell [failed] on the writing portion,” she tells me in Arabic. Her eyes, pale green and framed with delicate wrinkles, flicker with shame at the memory. After a few weeks recovering from the disappointment, Aisha rejoined her classmates in struggling through passages on market capitalism and civic history. Progress is glacial and discouragement a constant companion, yet in recent months the women of Beit Al-Maqdis have drawn inspiration from an unlikely figure: Donald Trump.

Though they cannot vote, these women are attuned to the election cycle and have been deeply shaken by Trump’s repeated calls for a “ban on Muslims” and similar proposals targeting Arab and Muslim communities. While some commentators have dismissed these threats as mere political grandstanding, the rhetoric has espoused real fear among many, including Boyle’s students. While some of these women report experiencing mild discrimination in the past, the political vitriol of recent months has whittled their former optimism into anxious pragmatism. Now, many of them are reaching for American citizenship as insurance against their worst fear: mass deportation. When asked why they want to become citizens, they no longer mention cultural attachment or civic aspiration; rather, their immediate and unanimous response is: “so they can’t send us away!”

For some, these insecurities are augmented by direct experience. Saada, a dimpled, effusive mother of five, still quakes a little as she recalls her first attempt to rent an apartment in Brooklyn. The landlord, seeing her headscarf, immediately rejected her application. “He said he can’t have anyone wearing hijabs in this building.” Saada’s face strains to hold an unconvincing smile as she relates the story to me in Arabic. “It upset me. But I controlled myself, I gathered myself up and walked out. Because, what can you do?” Another woman in Boyle’s class says she was approved for an apartment in a nearby building, but the landlord almost “changed his mind” when the woman brought her elderly, veil-wearing mother to live with her. “He was angry,” says the young woman, dark eyelashes dipping towards the floor. “He said, ‘Headscarf, okay, niqab, no.’”

Many of these women also fear these hostile attitudes could translate into physical violence—fears that are not unfounded. Following 9/11, hate crimes directed at Muslims—and those mistaken for Muslims—became a familiar phenomenon in the United States. In 2015, the FBI reported these incidents at a rate of about 12 per month, but the number tripled in the weeks following the Paris attacks in November of that year. The Council for American-Islamic Relations also reported unprecedented rates of vandalism at mosques and Islamic centers following the attacks, while the atrocities in San Bernardino and Orlando have further stoked Islamophobic attitudes. Anti-Muslim aggression has spiked in schools in recent months, prompting the Department of Education to release a nationwide advisory in February expressing concern over a “level of anti-Muslim bias and bullying” unmatched “since the days and months immediately after September 11.”

Sutrallah has been struggling to learn English for years, but this year is the first time she’s attempted to become naturalized. “It’s different now, because, you know, Trump.” She says his name with the trill of an Arabic rolling “r,” a look of dismay spreading across her face as she holds her citizenship textbook with a desperate grip. She hopes to take the exam in July, but admits she is far from ready. “Please, help. Please. English ... no good,” she pleads after class, thrusting her dog-eared workbook towards Boyle in supplication.

The 100-question test confronting Boyle’s students is a recent phenomenon. For most of American history, would-be citizens presented their petition to any local, state, or federal court. Judges were given full power of arbitration, charged with determining whether the person was “of good moral character,” demonstrating “an attachment to the principles of the Constitution.” Predictably, interpretations of these criteria varied widely. The twentieth century centralized the procedure, but also brought a much heavier emphasis on surveillance and control. Under the Alien Registration Act of 1940 (also known as the Smith Act), millions of non-citizens were fingerprinted and thousands were taken into custody under suspicions of anti-American associations.

These wartime developments represented a decisive shift in the American immigration model, which had gradually moved from an economic to a national security approach. A glance at the series of government bodies that have overseen immigration captures this evolution with poetic concision: originally handled by the Treasury Department and what was then the Department of Commerce and Labor, immigration was moved to the Department of Justice around World War II, and, in the wake of 9/11, handed over to the Department of Homeland Security.

The Arab women of Beit Al-Maqdis, while largely unaware of this history, keenly feel the impact of the current security-driven environment. “They think we are bad people, crazy people,” says Saada, shaking her head. Despite her nine years in the United States, she feels her place in America has grown only more tenuous since the rise of Trump. Aisha shares this anxiety. “I don’t know what will happen to us if he wins,” she says. “They can’t send us all back, right?” Her question rings like a plea. While these women understand—and share—American outrage at the atrocities of Islamic extremists, they are largely bewildered that so many people appear ready to make sweeping generalizations about Muslims and Arabs. “This killing, this ISIS, is not us!” blurts Saada, her hands flapping and her smile full of pain.

While the political climate has cast a pall on their lives, the women try to keep their sights set on what drew them to America in the first place: political freedom, economic opportunity, reprieve from violence. Sutrallah keeps her focus tight, carefully navigating the demands of American parenthood: parent-teacher conferences, doctor visits, grocery shopping, balancing the family budget. Her husband works in a Queens convenience store with two other Yemeni men, and the family splits his earnings between their own expenses and remittances to family back home.

Even after eleven years in the country, Sutrallah admits that she is not yet at home here. While she is vivacious among her Arabic-speaking peers, she is ashamed of her imperfect English, and seldom ventures outside her Bay Ridge enclave—a choice many of her similarly insecure classmates share. This sense of alienation sparks nostalgia for the communal living and familiar customs of Yemen. Despite the turmoil, she says, people in her hometown looked out for one another. “Everyone knows each other there, and everyone helps each other,” she recalls. “You are never alone.” On lonely days in Brooklyn, Sutrallah consoles herself that she is helping ensure a “better future” for her children, who, she boasts, speak “100 percent American English.”

Shura, a fellow Yemeni and Sutrallah’s classmate, is also thrilled that her children will grow up “a part of America”—but she’s not ruling herself out, either. “I want to make American friends, inshallah, when my English is better,” the 23-year-old tells me. “I think we could learn a lot from each other.” Arriving early for her lessons in a rustle of black gauze, Shura’s dark eyes harbor a spark so distinctive that I am able to recognize her even when, on the occasion a man is present, she pulls her niqab across her nose and mouth. While it’s been less than a year since she arrived in the United States, Shura has an instinctive grasp of English and can already hold simple conversations with volunteers from the Arab-American Association of New York. When we chat about her transition to the United States, though, we speak in Arabic, allowing her speech to match her soaring enthusiasm.

“Most of the people we meet here are really kind.” (Shura uses the Arabic word “lateef,” which connotes goodness of heart, wholesomeness, and beauty.) Shura arrived in New York City with her husband and infant just as the autumn air began to chill. When snow fell, she was enchanted. “I’d never seen it, except in movies,” she says. “We were all at the window the first day, taking pictures to send to our family in Yemen. We said, ‘See, the whole world is white! And beautiful!’ Subhanallah—glory to God.”

For now, Shura is concentrating on her language skills, but her aspirations extend far beyond Beit Al-Maqdis. “I want to go to college,” she repeats, frequently. She would like to work in translation, she says, in order to “help other Arabs in America, because it is very hard for them when they don’t speak the language.” She gestures with her hand, mime-like, as if pressing up against a solid wall. “Language keeps us apart from people. We want to speak. I want to say ... but I don’t know how.” Shura’s hands fall, palms up, on her lap. A moment later, she adds, in English, “It makes me feel ... stupid.”

While naturalization is an often graceless process, the women of Beit Al-Maqdis are still eager to praise their new country. One frequent point of admiration is American law enforcement, especially for those who left behind neighborhoods run by vigilantes or government thugs. “You don’t have to be afraid of police here,” remarks one Egyptian woman. “Back home, if you are taken by the police, that’s it—maybe you’ll never come back.” Shura nods, adding, “In America, if someone takes your rights—you can go to the courts. The law protects you.” When, during a citizenship lesson, Boyle touches on religious freedom, Sutrallah chimes in, saying, “This is good, very good.” Later, she remarks, “In Yemen, I only knew Muslims. Here, you meet all kinds of people: Jews, Christians, people with no religion. And this is good. Didn’t God make us all?”

Similarly, many of the women at Beit Al-Maqdis speak with delight about their expanded horizons. “In Yemen, many people don’t like their girls to go to school, and women don’t leave the house much,” says Shura, grinning, “but here, you have the right to go out, and move around, and do anything!” Sutrallah challenges Shura, reminding her that not all families in Yemen restrict their daughters—“just some of the tough-minded people, the uneducated ones. The ones who don’t understand Islam correctly.” Saada is conflicted, and wonders: What do young American children do, when their mothers are at work all day? On the issue of employment, the class is divided; about half of the women at Beit Al-Maqdis say they hope to attain higher education and find jobs—social work, nursing, teaching, and childcare are among the most common goals.

Standing across from

Sutrallah’s cramped desk, Boyle returns to question number three. “What are the first three words of the Constitution?”

Sutrallah hesitates, and her comrades erupt into a chorus of unsolicited assistance. “Con-stit-ushon! Distoor,” offers one, translating the word to Arabic. “Yiiiii, sister,” murmurs another, “What did she say?” Sutrallah begins to laugh helplessly, cupping small fingers over her mouth and sending thin bangles jingling down her black-sleeved arms. Boyle switches to Arabic, addressing Sutrallah in the lilting Cairo accent she picked up during her doctoral research in Egypt. “La itkhaefi—don’t get nervous. Listen carefully.” Sutrallah and her companions do listen—with painful concentration—as she scrawls the answer on the whiteboard: “We The People.” Those who can read English squint, mouthing the words, while the rest wait to hear their teacher repeat orally: “We. The. People.”

Hunching in their undersized chairs, contemplating America’s founding document, the women are caught up in the moment, forgetting the often hostile landscape they will have to negotiate once they leave the mosque. They are practicing the letter “p,” a sound not heard in the Arabic language. Having grimaced and laughed through many failed attempts, most of the women have now mastered the consonant—and it’s an important one.

“P-Pea-poll.” They repeat after Boyle. “We. The. Pea-poll.” Boyle gives high-fives. Encouraged, they continue their chorus. “We. The. Pea-poll. Yiii, tamam! [alright!]”