From the cable car threading its way up the mountains surrounding the Colombian city of Medellín, one can see the towers rising behind the peaks. The telltale signs of social housing—the monotony of the high-rises, the plain concrete facades, and, most noticeably, the lack of visible street life—stand in stark contrast to the sprawling landscape of shacks below, where commerce, construction, traffic, and domestic life all seem to be unfolding at once.

The cable car doesn’t actually stop anywhere near the social housing complex. It is natural to wonder how residents survive in such an isolated locale. This situation reflects the conundrum that bedevils social housing around the world. What is meant to be a boon to low-income residents becomes a burden—a house that never becomes a home.

Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, along with his architecture collective Elemental, tried a different approach in 2004 when designing Quinta Monroy, a social housing project in Iquique, Chile. Elemental, which Aravena calls a ‘do tank,’ is not a typical architecture firm, but rather an equal partnership between five architects, the Universidad Católica de Santiago, and the Chilean oil firm, COPEC. With a tight budget limited by the state housing subsidy of $7,500 per house, Elemental spent most of the funds on purchasing the land where the residents already lived, in an informal settlement within city boundaries. The remainder of the budget was spent on the housing itself.

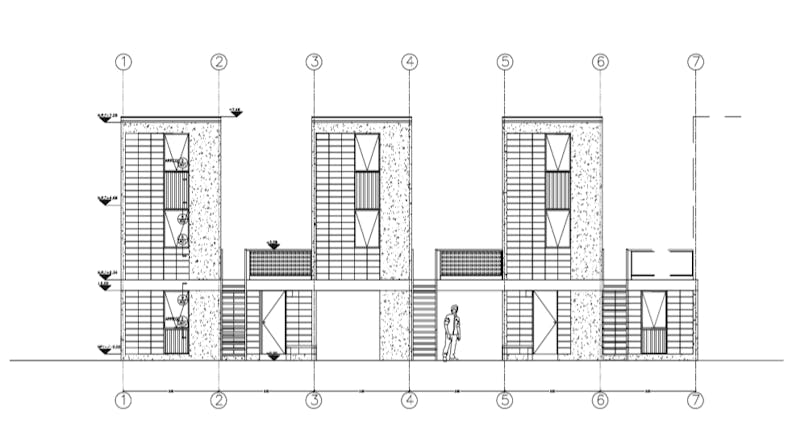

But instead of building complete homes with tiny footprints, as most developers would have done, Elemental constructed just half-homes, three-story structures that included a kitchen, a bathroom, structural walls, and a staircase. The rest of the houses, allotted empty slots between the half-buildings, were left to the residents themselves to construct, offering double the space normally given to social housing residents. This spacious footprint was one of Elemental’s principles of incremental social housing—what it calls “middle-class DNA,” or housing that could expand and become more valuable as residents improved the homes with their own labor and resources.

At Quinta Monroy, the value of the houses rose rather than fell, unlike the case in many social housing projects. Most importantly, the residents did not have to pack up their lives and head for the hills. They were still in the city, where they had jobs and networks, so there was an incentive to stay. Since constructing Quinta Monroy, Elemental has designed a total of 2,500 homes applying similar principles of incremental building, density, and proximity to an urban center.

This year, architecture’s most prestigious honor, the Pritzker, went to Aravena in recognition of such work. The jury citation stated that Aravena “epitomizes the revival of a more socially engaged architect, especially in his long-term commitment to tackling the global housing crisis and fighting for a better urban environment for all.” While he has also designed institutional and private commissions, the jury noted that “what really sets Aravena apart is his commitment to social housing.”

Some were surprised by the choice. For most of the award’s history, the Pritzker has been granted to iconic architects at the apex of their careers, most of whom are known for their formally inventive structures, as well as to architects of notable vernacular architecture (an approach that uses local materials or building techniques unique to a region). But Aravena has staked his reputation not on the design of monumental buildings, but rather on half-buildings—or “half of a good house,” as he calls his social housing prototypes.

What is not in doubt is that the need for low-cost housing is pressing. As Aravena himself noted in a 2014 TED talk, the rapid growth in the world’s urban population means that a city of one million people must be built every week until 2030. In Chile, where Aravena is based, almost 90 percent of the population already lives in cities, and the housing deficit requires that nearly 100,000 units be built every year. Can Aravena’s approach help house the world?

Since the 1950s, self-help housing has been a way for the urban poor to gain access to shelter, often through unsanctioned land occupations upon which residents build their own houses without any outside assistance. Alan Gilbert, a geography professor who has studied housing in Chile and in Latin America for 40 years, commented, “The idea that you build half a house, effectively, and leave the residents to build the rest, is not new in Latin America.” He explained, “In most cities in Latin America, most of the building over last 50 years—depending on the city—40, 50, 60, 70 percent has been through incremental construction.”

Approximately a fifth of the world’s population lives in such informal settlements, where residents have no legal claim to the land or to their houses, and often have no formal access to services like running water, electricity, and sanitation. Many of the world’s oldest and largest informal settlements were first built on the periphery of cities, but over time have been incorporated well within city boundaries, and now occupy prime real estate. This poses a significant challenge.

“In cities like Mumbai or Nairobi and Kampala … now that the value of that land has grown exponentially, the incentive to evict those people and give the land to private developers is high,” said Ariana MacPherson of Slum Dwellers International (SDI), an international network of organized communities of urban slum dwellers from more than 20 countries. Most governments perceive incremental housing settlements as an eyesore, a visible reminder of poverty amidst glittering skyscrapers and business districts, while private landowners tend to prefer high-income tenants and developments over the urban poor.

For groups like URBZ, an urban research collective based in India, informal settlements are home to incredibly rich social and economic networks that are integral to the city—areas that URBZ calls “communities in formation.” URBZ helped stop the demolition of Dharavi, a sprawling informal settlement in Mumbai that is one of the world’s largest. But it took much campaigning by residents to persuade politicians to preserve the settlement. There is certainly no recognition of the creativity residents have shown in making viable living spaces with their limited resources. (Geeta Mehta, an architect and one of the founders of URBZ, found it ironic that “the slow incremental development in Dharavi is not legit, but what Aravena is doing is legit because it’s architecture. There should be a conversation about the definition of what architecture is.”)

Social housing is often offered by governments as a more secure alternative to informal settlements. Yet most social housing is constructed in remote or isolated locations, and become associated with stigma, crime, and deteriorated conditions. “You can build millions of housing units in a piece of desert, 40 kilometers from the city center where the land is worth nothing,” said Christophe LaLande, leader of the housing unit at U.N.-Habitat, the United Nations agency dedicated to human settlements. “Yes, you have a house, you have a shelter, but if it’s not connected to your job, if it’s not connected to services, in terms of education, health, if you have very poor communication, transport system … that’s not adequate housing as such.”

Aravena’s work learns from the two approaches, joining the political legitimacy and infrastructural access of social housing with the adaptability of self-help housing. But can this model be reproduced in other contexts? This question seems to be on Aravena’s mind as well. Since winning the Pritzker, Elemental released four of its social housing designs for download from its website, including the design for Quinta Monroy. While acknowledging that the designs would have to be adapted to local laws and codes, Elemental said it hoped “to rule out one more excuse for why markets and governments don’t move in this direction to tackle the challenge of massive rapid urbanization.”

Ann Varley, a professor at University College London who has studied informal settlements in Latin American since the 1980s, said she had serious questions about the reproducibility of the Quinta Monroy model. She recalled government social housing projects to the south of Guadalajara, Mexico, that “were like barracks for the urban poor. You’ve taken the poor and you’ve just dumped them miles out into the countryside.” The social housing she has studied in Mexico also showed signs of shoddy construction, sometimes resulting in such unsafe conditions that residents had to be evacuated. In such cases, she added, it is not clear whether it is better to live in informal settlements or in social housing. She cautioned that without the economic and political conditions that make Quinta Monroy a successful social housing case, there is a danger that Aravena’s work could serve merely as a hollow aesthetic showcase rather than function as a viable housing model.

The most pressing requirement for reproducing a project like Quinta Monroy is the ability to purchase affordable land within city boundaries. But there are doubts that cities with severe land shortages would be amenable to such projects. Gilbert noted that some Chilean cities, like Iquique, are located on more flat terrain, while other major cities in Latin America, like Caracas or Bogota, are hemmed in by mountains, affecting the supply and cost of land, as well as the cost of building on such terrain.

The majority of Aravena’s social housing work has also rested on the unique conditions and high level of investment from Chile’s social housing program. For decades, the Chilean housing ministry has granted housing subsidies directly to qualified low-income residents, a process that privatizes the production of social housing and removes it from the purview of the state. Chile’s subsidy-based model has long been a shining beacon for international development agencies and neoliberal economists, and has since been adapted in Ecuador, Panama, Colombia, and other countries, to varying degrees of success. However, Gilbert cautioned that Chile’s model cannot be instituted elsewhere without a change in mortgage, banking, and pension systems. In addition, according to Gilbert, many housing ministries are often loath to relinquish control over housing budgets and contracts, which are considerable sources of political power and capital.

That the Chilean government has invested more than many other governments in social housing is also contingent on the country’s unique history. What is often ignored is the history of massive, organized land seizures in Chile that forced the government to stop treating housing as a commodity. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, up to 14 percent of Santiago’s population took part in regular land seizures, and some 50,000 people took part in such actions even under Pinochet’s rule. Edward Murphy, a professor and author of For a Proper Home: Housing Rights in the Margins of Urban Chile, 1960-2010, asserted that a considerable organized left forced the state to recognize housing as a basic right, which is still a belief shared by the majority of Chilean citizens and those in government.

However, in places where housing isn’t sacrosanct, the fixation on transforming the poor into homeowners can spur unintended and sometimes negative consequences. In Dharavi and other informal settlements in India, URBZ’s research has found that many residents are far more interested in keeping their rural land as a home base, rather than becoming permanent urban residents, as is often the case in Latin America. As “housing is a right” discourse entered India from Latin America, the different needs of urban migrants were collapsed into a single program—to make them homeowners. As URBZ founder Rahul Srivastava explained, “Maybe one-third of the population only needs a place to come and work six months a year, maybe one-third of the population needs to come and only work here for four to five years without investing in a house, they just need a cheap rental place to live in.”

He continued, “A lot of people have been co-opted into a system where they believe that even to live a dignified existence as a worker in the city, they need to invest completely as citizens to get a house.” Housing then becomes a bargaining chip between the poor and local politicians. “The politicians will say—that if you want even a tiny place to live outside the market, then you come to me and I will only give it to you in exchange for votes. This is the way in which a lot of the narrative of housing—however liberated it sounds—actually occurs.”

Some point out more fundamental limitations of Aravena’s approach to incremental social housing. Isn’t asking the poor to shoulder more of the housing burden an inherently unfair proposition? In an article, Chilean architecture professor Fabian Barros asked whether Aravena’s approach “paradoxically reproduces what it tries to fight.” In his view, the provision of just half a house “produces inequality, as it considers the inhabitants of these homes as beings from another social class who can live in half-finished houses without privacy and in highly degraded environments.” At the Santiago, Chile, university where Aravena teaches, a group of students even constructed a shantytown installation called “Incremental” to protest the architect.

Still others question the limitations of a housing strategy that does not fully address the problem of segregation. Mehta referred to Aravena’s open-source offering as a “gimmick.” She asked, “Where is the infrastructure? Where is the connectivity? Where are the empowering elements of the city that give a poor person an equal opportunity in a city to travel, to get a job, to have telecommunications?” Murphy, who has studied the resident experiences of one of Aravena’s Chilean housing projects, noted that this question was very pertinent for social housing residents in Chile. The high level of attention that Chilean campamento residents received from the government often faded once they had moved into social housing. He explained, “There’s a sense that they have what they demanded…that they’re no longer poor because they live in this kind of housing.” But many social housing residents may find themselves heavily indebted, paying for their children’s education or other necessities. For many housing activists and residents who had fought for the right to a home, the question became “about the need to have not just housing, but a life of dignity,” said Murphy.

Mehta also questioned who is ultimately profiting from the social housing in an Aravena project. If the contracts award the subsidies to outside contractors or developers, they do not have the same accountability as the residents themselves. “We are taking out the real stakeholders out of this machine, and we are giving it to a developer to make half a house which is aesthetically acceptable to architectural magazines,” she said.

Instead, she suggested that government funds for informal settlements be distributed to communities themselves so that they can decide whether it is housing they need most or another service or infrastructure. Public funds can thus be used to build up local economies and infrastructure, encourage the use of locally available materials, support construction by residents, and train marginalized people in construction, resulting in a more empowering process overall.

As global leaders meet this year for Habitat III, a U.N. conference on human settlements that meets once every 20 years, the question of housing will be central to the discussion as never before. With climate change, the global refugee crisis, and numerous natural disasters adding to urban housing shortages, the need for low-cost housing has moved to the forefront of many national and regional debates.

As Lalande of U.N.-Habitat noted, “Something that should be promoted much more is that housing is not an architectural product. … It’s the result of a social process, a cultural process.” Such a framework might then move away from one-size-fits-all models, and open the field to anyone, whether or not they are architects.

Perhaps Aravena’s greatest contribution to the housing debate is his exhortation to architects to move beyond the traditional definition of what it means to be a designer. How would design be transformed if architects engaged more meaningfully with other disciplines, whether it is urban policy or law or economics? What if architects listened more carefully to the people they want to build for? And most importantly, what would emerge if they faced the challenge of the global housing deficit head-on?