For specialty food manufacturers across Europe, location equals brand. While Roquefort and gorgonzola cheese might resemble each other in their crumbly texture and unique smell, the former must be made from a specific strand of mold found in the French caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, while the other is produced in the northern Italian regions of Piedmont and Lombardy. If it’s not made in Italy, it’s not gorgonzola.

“Champagne” is perhaps one of the most serious and litigious of these designations; it can only be prepared and produced in the French province that bears its name, using the méthode champenoise—all other bubbly wines are simply “sparkling.” The protection extends to all aspects of the brand. In 2013, the Interprofessional Committee for Champagne Wine preemptively warned Apple that that newest iPhone color could under no circumstances be described as “champagne.”

The European Union’s Protected Designation of Origin status guarantees and safeguards the authenticity of many regional and traditional foods, from celery to cider. Britain currently has more than 60 beverage and food products with protected designations: The long, peppery pinwheel of Cumberland sausage can only be sourced and produced in the English county of Cumbria, and Yorkshire Forced Rhubarb can only be grown in the “Rhubarb Triangle” in West Yorkshire. If the United Kingdom votes in Thursday’s referendum to leave the EU, those protections will disappear, and manufacturers across the globe could start claiming to make Scotch whisky or Stilton cheese, possibly pushing local producers out of business.

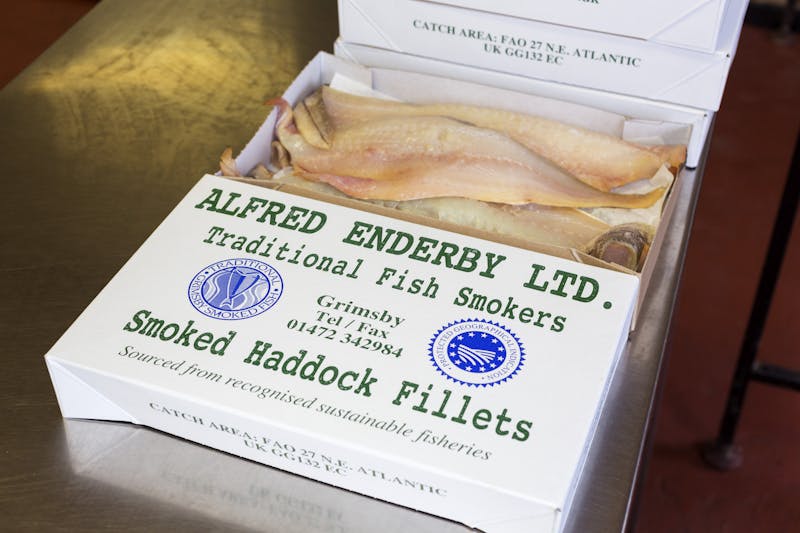

Photographer Martin Parr was born in Epsom, England, provenance of Epsom salt, which does not hold any kind of protected designation. A documentarian of British working life, Parr visited manufacturers around the U.K. in the lead-up to the Brexit vote to see how they produce their specialized foods.