What if every book was worth reading? Not just the books with silver medallions on their covers, but every hardcover featured at Barnes & Noble, every paperback foisted upon you by a friend or a relative or even a stranger—what if they were all pretty good? That’s the sense one gets from Book Marks, a new “Rotten Tomatoes for Books” launched Tuesday by the literary culture site Lit Hub. Unlike Rotten Tomatoes, which determines if a review is “fresh” (red tomato) or “rotten” (splattered green tomato) and assigns a percentage score, Lit Hub uses an A-F grading system. But none of the books are remotely in danger of flunking.

The reviews themselves have been pulled from 70 publications, including The New Republic, but only a few have been graded below a B-: Curtis Sittenfeld’s novel Eligible, the Prep author’s take on Pride and Prejudice, is one—it got a C+; Emily Winslow’s memoir Jane Doe January, about the 20-year search for the man who raped her, is another—it got a C, based on three middling reviews. Both Elena Ferrante’s The Story of The Lost Child, perhaps the most acclaimed work of fiction published in the U.S. in 2015, and Andrew Nagorski’s The Nazi Hunters, a dad book about Nazi hunters, have A grades. Whereas Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich’s masterpiece Secondhand Time has an A-, Steve Hamilton’s thriller The Second Life of Nick Mason is one of four books to have earned an A+. Even Moby’s memoir, Porcelain, got a B-.

That is, nearly all of the more than 100 books graded by Book Marks seem to be worth reading, which renders it somewhat useless as a recommendation resource, which wasn’t lost on many of its early readers. But that’s not how Lit Hub editor-in-chief Jonny Diamond pitches the site anyway.

“One of the central purposes of Book Marks is to draw attention to all the great critical writing about books happening in the country today, to create an easily searchable resource that reflects the current state of literary criticism,” Diamond told me. “We also hope that it will help elevate worthy books that receive strong accolades but do not have big marketing budgets behind them and might otherwise be overlooked. Finally, we hope that readers will benefit from Book Marks, using it to discover books that they will find interesting and rewarding.”

What if the problem, then, isn’t that Book Marks insufficiently separates the great books from the mediocre ones? If it is doing exactly what it was designed to do—reflecting the current state of literary criticism—then the real problem is that literary criticism, like America’s universities, is suffering from severe grade inflation.

This is not a new debate. Literary criticism has been routinely lambasted for its niceness, its lack of intellectual rigor, and its mediocrity. n+1’s first issue took on The Believer, which “[differed] in at least one particular from, say, the New York Review of Books, in that its overt criterion for inclusion is not expertise, but enthusiasm.” Writing in Slate in 2012, the critic Jacob Silverman decried the effect of social media on reviewing, arguing that it made incisive criticism more difficult because your potential targets were almost always connected to you in some way: “Reviewers shouldn’t be recommendation machines, yet we have settled for that role, in part because the solicitous communalism of Twitter encourages it.” (In 2013, meanwhile, Clive James took to The New York Times to tell Americans that they simply weren’t good at writing hatchet jobs.)

Why are book reviews so damn nice? Many argue that America has few professional critics left, which means that most of the criticism is being done by freelancers who lack institutional protection and therefore are disincentivized from making sharp critiques. Freelancers are more likely to be drawn to books that they like because, unlike a professional reviewer, they have no obligation to review a hot new novel. They may also want to publish books themselves, so they’re loath to piss off potential publishers.

Furthermore, the literary community itself—if such a thing exists—is miniscule. Reviewers may have met the author they’re reviewing, either in person or online. (For instance, in full disclosure, I am friendly with Diamond and at least half of Lit Hub’s staffers and regular contributors. So if I’m being too nice, blame that familiarity.) Also, reviewers are often authors themselves, and would hope to be treated kindly when the tables are turned.

Wall Street Journal book critic Sam Sacks attributes the niceness partly to compassion.

“For better or for worse, book reviewing tends to be a gentler field than film reviewing, since it’s more socially palatable to attack the misfires of some bloated movie studio than an obscure solitary novelist,” he told me over email.

But there are more practical reasons why literary criticism is more generous than film or music writing, and why, by extension, a “Rotten Tomatoes for books” doesn’t make much sense. As Sacks notes, “Reviews exist in part to help readers decide what to read, of course, but not through a grading or point system, like in Consumer Reports…. I love a satisfying hatchet job, but what most good reviews try to do is explore a book rather than merely pronounce on it. They try to dig into its style and ideas and meanings as well as evaluate its execution. It’s not uncommon that I’ll ‘like’ a book because it failed interestingly. These reviews presume a similar sort of readerly engagement. At the most fundamental level, they treat readers like people who can think for themselves.”

Book Marks aims to treat reviewers in much the same way. When asked why the site isn’t transparent about its grades—individual reviews are quoted, but readers can’t see the grade awarded to the review—Diamond said it was because he hoped Book Marks would become a discoverability engine for criticism as well as books. “We feel that by not displaying grades at a review level, we encourage readers to read the individual reviews and engage with the complexity and nuance of the reviewer’s take,” he said.

Indeed, many of the reviews cited by Book Marks are best read after reading the book, not before it. Which makes one wonder why they’ve bothered slapping a grade on them in the first place.

The kind of literary criticism Sacks is speaking about, and which Book Marks collects, represents a relatively narrow swath of what’s actually published. Yes, there are tabs for Mystery and Science Fiction and Romance, but the works displayed are comfortably literary, even if some have genre elements. (For instance, the thrillers by Hamilton and Laura Lippman are known euphemistically within the publishing industry as “crossover” works.) These are, with a few exceptions, books that could be considered as National Book Award contenders. There’s no Jackie Collins, no Jennifer Weiner, no James Patterson, no hard sci-fi.

This is where Rotten Tomatoes ultimately serves as a limiting comparison. For one thing, even in this golden age of content, there are many more books released every week than movies, which puts a strain on already strained book reviews. It’s rare that, say, the New York Times Book Review would review a work by James Patterson, whereas their film critics would undoubtedly review the newest Michael Bay movie. Rotten Tomatoes covers all films because there are fewer of them: While most of the books on Book Marks seem to have four to six reviews, you’d be hard-pressed to find a new mainstream movie on Rotten Tomatoes with fewer than 40. (It helps that Rotten Tomatoes adds reviews from many obscure-ish film blogs.)

To Lit Hub’s credit, the most nefarious thing you can say about Book Marks is that, as John Warner wrote on Twitter, it’s a branding exercise. Despite the fact that Lit Hub is owned by Grove publisher Morgan Entrekin and is partnered with many other publishers, who advertise on the site and provide it with excerpts, Diamond told me that Book Marks will include all reviews from their sources, “positive or negative.” When asked if Book Marks would ever turn into a site that made money by linking to Amazon or other affiliate-driven sites, Diamond said that they “have no plans to sell books, for many reasons: one being that Literary Hub is a supporter and partner of independent bookstores and we encourage people to shop locally.”

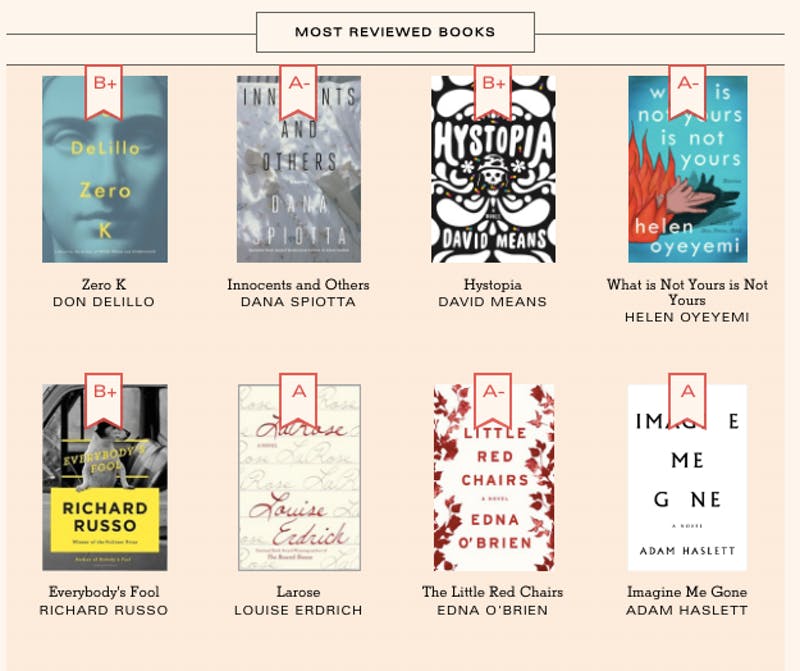

Book Marks may very well prove to be efficient and helpful for its readers—and may even bring new readers to books of quality. But it won’t appreciably expand the dwindling audience for literary fiction. My favorite novel of the year, Dana Spiotta’s Innocents and Others, has an A on Book Marks and it’s also sold fewer than 5,000 copies in hardcover, according to Book Scan data. My second favorite book, David Means Hystopia, also has an A. It’s sold less than 2,000. There’s nothing here to suggest that aggregating the handful of reviews of that book and assigning a grade to them will help that book find an audience, however worthy it is. According to a source who has seen figures circulated by Lit Hub, the site receives around 600,000 unique visitors a month, which makes it one of the most-visited literary websites around and gives you a sense of how small the dedicated audience for literary fiction is. (While that 600,000 figure trumps competitors like The Millions and The Los Angeles Review of Books, its audience is a third the size of Book Riot, a more populist book site, per Quantcast.)

That’s not Book Marks’ fault; you can’t rate a project based on an ambition it doesn’t claim to have. But what this new project (and the instant reaction to it, including this article) can reveal is that “literary fiction” is in trouble. The reviews need more visibility, yes, and each book needs more attention. But mostly, the industry needs more readers. Book Marks won’t create them and it doesn’t help the ones who already exist, particularly because the site focuses on mainstream literary fiction that most regular readers are already aware of. The issue isn’t that the right books aren’t rising to the top—it’s that there are too many books, all of them pretty good and pretty much the same, and too few readers to absorb more than a handful of them any given year.

The reception to Book Marks has been mixed at best, with most of the criticism being directed at the use of a letter grade. The grades have mostly come under attack because there’s an idea that grading things and evaluating them are mutually exclusive, or that grading books is simply not a generous thing to do, as if the grades were not (admittedly somewhat arbitrarily) applied to considered works of criticism. Both of these arguments strike me as tribalism more than anything else—of circling the wagons around sensitive artists, to prevent them from having to hear the mean things that are being hurled at them by boorish critics. And both arguments ignore the fact that the authors have nothing to be afraid of: The reviews being aggregated almost entirely treat the books in questions very well. In fact, the grade is essentially meaningless—it does nothing to distinguish the hundreds of books being “graded” because nearly 99 percent of the grades are Bs or As.

One could look at this as grade inflation, as an epidemic of niceness, of good reviews being participation trophies—as long as you write a good enough novel, you get a good enough review. But the issue, I think, is not cultural decay but cultural homogeneity: The books being well-reviewed on Book Marks are the same books you see everywhere, if you pay even passing attention to literary culture. Magazines and websites showcase their own good taste by reviewing them; these reviews are then aggregated and given an arbitrary letter grade by Lit Hub, which then magnifies the wider acceptance of good taste to everyone. But by not including more commercial works, or books by smaller presses—neither of which are regularly reviewed by the kinds of outlets being aggregated here—Book Marks is a reflection of literary publishing’s insularity, and it suffers for it.

By limiting its aggregation to reviews from generally well-established outlets, Book Marks limits its populist appeal. Most of, if not all, of the sites and publications contributing reviews meet regularly with publishers and tend to align around certain “hot” books. Including more books from outside of these media outlets and traditional literary publishers would both push readers to try books they might not encounter otherwise, and hopefully push critics to adopt a wider vocabulary. (This might also widen the range of grades given, but perhaps that’s asking too much.) Book Marks is a flawed tool, but its most glaring flaws reflect those of the wider literary culture. For it to succeed, it needs to challenge that culture.