Muhammad Ali was brutal in the ring. It’s painful to watch his early matches with Sonny Liston, Floyd Patterson, and Ernie Terrell, which seem not at all like contests of equals but exercises in punishment and retribution verging on torture. Ali regarded these foes as not his boxing rivals so much as traitors to the cause of black freedom. Terrell, his former sparring partner, snidely kept referring to Ali by his birth name, Cassius Clay, in the buildup to their 1967 fight, an affront to the champion who had shed what he saw as a slave name for one that affirmed his identity as a black Muslim. “What’s my name, Uncle Tom?” Ali kept yelling as he pummelled Terrell. “What’s my name?” Even as Terrell buckled, Ali kept going after him with unforgiving cruelty.

The great paradox of Ali is that this man whose livelihood was violence, who was so relentless and unpitying in the ring, was a man of peace. The greatest act of his life didn’t involve fighting but rather refusing to fight. It was Ali’s decision in 1966—taken at great personal cost and risk—to defy orders to join the military during the Vietnam War that made him one of the greatest American heroes.

Ali’s critics called him a draft dodger, an accusation still flung around by the right-wing press and by conservative politicians. The real draft dodgers of the era were those who supported the Vietnam War but benefitted from the loopholes of the system to avoid service, chickenhawks like Dick Cheney, Newt Gingrich, and Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol. Ali’s relationship with the draft was different.

In truth, if Ali had wanted an easy life, he would’ve allowed himself to be drafted. There was no way the military would have sent the heavyweight champion of the world into combat to be maimed or killed. As the documentary The Trials of Muhammad Ali (2013) makes clear, Ali’s managers had been preparing a sweetheart deal with the military so that his service would be only symbolic. Like Joe Louis in the Second World War, Ali could’ve had an easy time in the Army, fighting charity matches and raising morale.

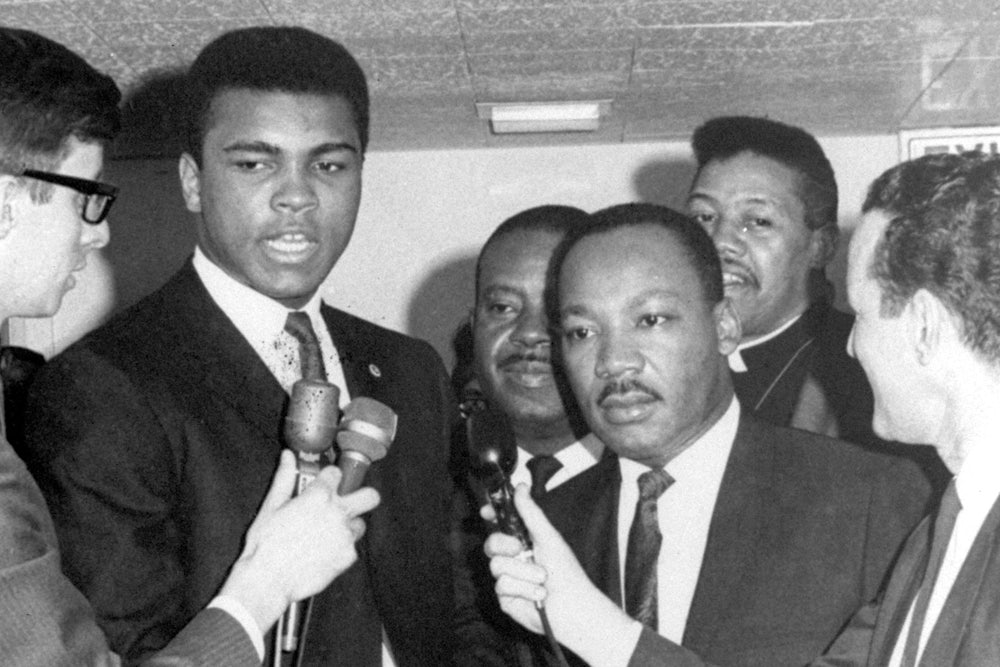

Ali chose not to because he was sincerely opposed to the Vietnam War—which he rightly saw as an imperialist adventure—and indeed to all war. The sincerity of his pacifism was affirmed by the Supreme Court in an 8-0 decision. (The ninth justice, Thurgood Marshall, recused himself because he had belonged to the NAACP, which supported Ali in the case. Marshall would almost certainly have agreed with the other eight justices.) More importantly it was affirmed by Ali’s own actions, by the fact that he risked a jail sentence of five years and lost millions of dollars and three-and-a-half of his prime years as a champion boxer. Writing in The Nation, Dave Zirin rightly sees Ali as an essential figure who brought together the black liberation movement with the anti-war movement, forging a path followed by Martin Luther King, Jr. who came out against the Vietnam War a year after Ali.

It was Ali’s anti-war stance that made him a global hero. Prior to his defiance of the draft, he was a funny, showboating boxer who belonged to an eccentric religion. But in making his case against the war, Ali went on speaking tours where he honed the cheeky eloquence that would be his trademark. Here, he speaks at a rally in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1967:

Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No, I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end.

I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom, and equality. ...

Ali’s words carried the force of his personality. The typical abuse hurled on pacifists, that they are cowards or weaklings, seemed absurd in the face of Ali’s bravery not just in the ring but also as a critic of racism. That he was willing to give up everything—his liberty, his income, his status as a champion—for his beliefs made him a hero. And the connections he drew between opposing racism at home and imperialism abroad put him on the most radical wing of African-American politics.

The stance Ali took on Vietnam has, of course, been vindicated by history. The injustice of the war is no longer controversial among reasonable and sane people; even its key architect, Robert McNamara, admitted it was wrong, based on a misunderstanding of the enemy and sold to the public with lies. The United States is not only at peace with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, but is actively courting it as an ally in order to contain China (a country which McNamara and his crew idiotically saw as Vietnam’s puppet-master).

During his rich and complicated life, Muhammad Ali did many things good and bad. But the finest thing he ever did was standing, in the face of fierce public condemnation, against a foolish and criminal war. RIP.