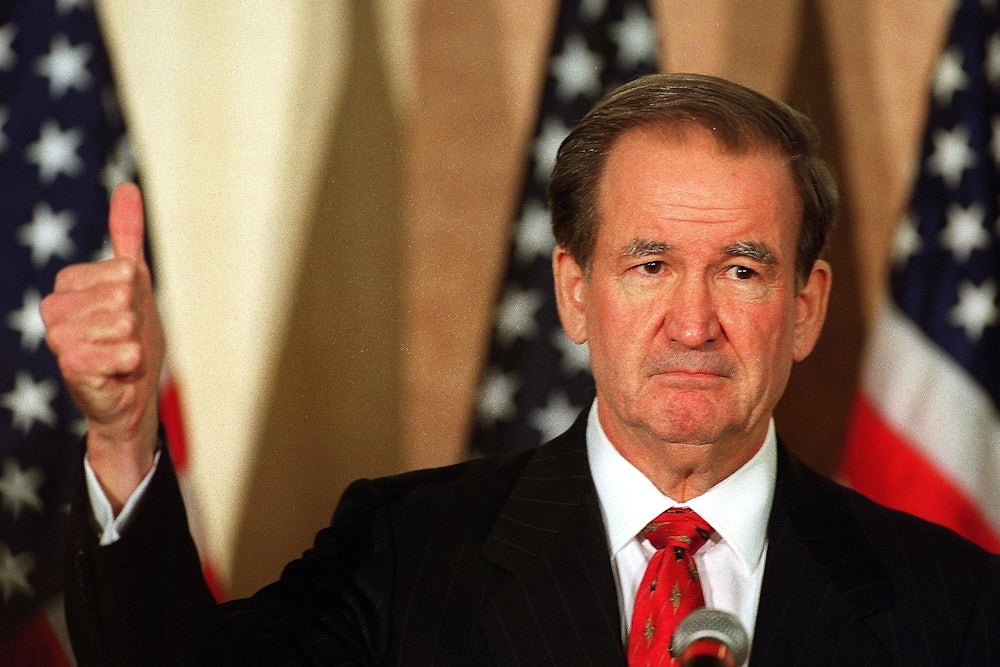

Many pundits opine about Donald Trump, but few do so with the special authority of Pat Buchanan. While Trump has several important precursors such as George Wallace and Ross Perot, no other political figure prefigured Trump quite so exactly as Buchanan. As Sulla was to Julius Caesar, as John the Baptist was to Jesus, as Gabriele D’Annunzio was to Benito Mussolini, so Buchanan is to Trump: the harbinger, forerunner, and prototype who embodied in rudimentary form the ideas and actions that a more famous figure would use to change the world.

In his three presidential runs in 1992, 1996, and 2000, Buchanan was the first to brew the particular cocktail of issues that we now call Trumpism: white resentment politics in revolt against globalization and bound together by immigration restriction, trade protectionism, and a unilateralist (or “isolationist”) foreign policy. Earlier this year, after Buchanan argued on CNN that Trump is “the new Buchanan,” Trump tweeted his approval: “Pat Buchanan gave a fantastic interview this morning on @CNN—way to go Pat, way ahead of your time!” With Trump now the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, ideas that were once “ahead” of their time (despite being reactionary) are now mainstream.

In his most recent syndicated column, “The Great White Hope,” Buchanan offers a remarkably candid account of the racist resentment that fuels Trumpism. Buchanan’s column is worth a detailed look because his forthrightness is a corrective to the tendency of other political commentators to ignore racism as a factor in Trump’s rise and focus instead, euphemistically, on economic anxiety. More deeply, Buchanan shows just how unhinged this brand of politics is, so much so that it is virtually a parody of itself.

According to Buchanan, Trump is the avatar of white males, the only Americans against whom “it is not only permissible, but commendable, to discriminate.” Buchanan rehearses the plight of the white working class—some of it genuine (the collapse in health in that cohort, although Buchanan fails to note that women are much worse effected than men), but much of it weirdly divorced from reality.

“In the popular culture of the ’40s and ’50s, white men were role models,” Buchanan writes. “They were the detectives and cops who ran down gangsters and the heroes who won World War II on the battlefields of Europe and in the islands of the Pacific.” Now, Buchanan laments, “everything has changed In Hollywood films and TV shows, working-class white males are regularly portrayed as what was once disparaged as ‘white trash.’”

In what world does Buchanan live where popular culture—including stories of detectives, cops, and war heroes—isn’t overwhelmingly dominated by white men? No less than seven of the 10 movies of 2015 feature white male heroes, whether they were roguish ex-smugglers (Star Wars: The Force Awakens), Navy veterans (Jurassic World), superheroes (Avengers: The Age of Utron), street racers (Furious 7), political revolutionaries (The Hunger Games), astronauts (The Martian), or spies (Spectre). In fact, the only movies in the Top Ten that don’t feature white male heroes are Inside Out (where the main character is a white girl with a loving father), Cinderella (where the white princess ends up marrying a white prince) and Minions (where, finally, Buchanan has a legitimate complaint since the weird heroes are little yellow men). To be sure, in some of these movies the white male heroes have to share the spotlight with women and people of color. Maybe that’s the true complaint.

It’s long been easy to poke fun at complaints that white men have been kicked off their cultural pedestal. In 1956 Life magazine published a special issue devoted to “The American Woman: Her Achievements and Troubles.” Writing in The New Yorker, John Updike parodied the glibness of Life and also a certain type of male me-too attitude by writing “The American Man: What of Him?” Mimicking the obtuse voice of Life, Updike wrote: “Ever since the history-dimmed days when Christopher Columbus, a Genoese male, turned his three ships (Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria) toward the United States, men have also played a significant part in the development of our nation. ... Lord Baltimore, who founded the colony of Maryland for Roman Catholics driven by political persecution from Europe’s centuries-old shores, was a man. So was Wyatt Earp. ... Calvin Coolidge, the thirtieth Chief Executive, was male. The list could be extended indefinitely.”

The arbitrary and absurd list Updike wrote as mockery, Buchanan now pens in utter sincerity: “Lincoln and every president had been a white male. Middle-class white males were the great inventors: Eli Whitney and Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell and the Wright Brothers. They were the great capitalists: Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford and J. P. Morgan. All the great captains of America’s wars were white males: Andrew Jackson and Sam Houston, Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, U.S. Grant and John J. Pershing, Douglas MacArthur and George Patton.” (The inclusion of Confederate heroes Stonewall Jackson and Lee in the pantheon is revealing, as is the praise Buchanan gives elsewhere in the column to the “statesman” John C. Calhoun.)

White racial resentment, in the hands of Buchanan no less than Trump, has become a self-parody, the barely coherent mutterings of men who can’t stand that the world is changing. For instance, Buchanan points out that that prior to the election of Barack Obama, “Lincoln and every president had been a white male.” True enough: White men indeed no longer make up 100 percent of the presidents. They are down to 97.75 percent. But this, in turn, somehow translates to the burning need to elect Donald Trump, whose belligerent attacks on Hispanics, Muslims, and women promise a restoration of white male authority in America.

The fact that Buchanan is openly lamenting the loss of the period when “every president had been a white male” gives credence to perhaps the most persuasive account of Trump’s rise: Jamelle Bouie’s argument that Trumpism is a backlash against the way Obama’s presidency has upended the traditional racial hierarchy. As Bouie wrote at Slate:

In a nation shaped and defined by a rigid racial hierarchy, his election was very much a radical event, in which a man from one of the nation’s lowest castes ascended to the summit of its political landscape. ... For millions of white Americans who weren’t attuned to growing diversity and cosmopolitanism, however, Obama was a shock, a figure who appeared out of nowhere to dominate the country’s political life. And with talk of an “emerging Democratic majority,” he presaged a time when their votes—which had elected George W. Bush, George H.W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan—would no longer matter. More than simply “change,” Obama’s election felt like an inversion. When coupled with the broad decline in incomes and living standards caused by the Great Recession, it seemed to signal the end of a hierarchy that had always placed white Americans at the top, delivering status even when it couldn’t give material benefits.

With Obama as the figure proving both that the nation has changed and that it will transform even more in the future, the once-marginal ideas of Buchanan were ready to be seized by a candidate like Trump in a successful bid for the Republican nomination. That’s how an idea so easily parodied became so politically marketable—and so dangerous.

If we see Buchanan and Trumps as racial nostalgists who want to return to a pre-Obama America, then Buchanan’s column ends on an ominous note. Buchanan asks: “Is it so surprising that the Donald today, like Jess Willard a century ago, is seen by millions as ‘The Great White Hope’?”

The phrase “The Great White Hope” has a disturbing history. It was used to describe several boxers who tried to unseat Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight champion. It was first cooked up by the novelist Jack London to describe James J. Jeffries. “Jim Jeffries must now emerge from his Alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face,” London wrote. “Jeff, it’s up to you. The White Man must be rescued.”

When Johnson defeated Jeffries on July 4, 1910, white mobs went on rampages all over America, in twenty five states. They killed at least 20 people and injured hundreds more. The racist politics Buchanan and Trump champion is easy enough to mock. As recently as last year, Buchanan looked like a fringe figure, a failed political candidate who represented an increasingly marginal minority of extremists. But with Trump as the head of one of the two major parties, and deadlocked with Hillary Clinton in recent general-election polls, Buchanan’s openly racist rationale for Trump’s presidency should excite anxiety more than mockery.