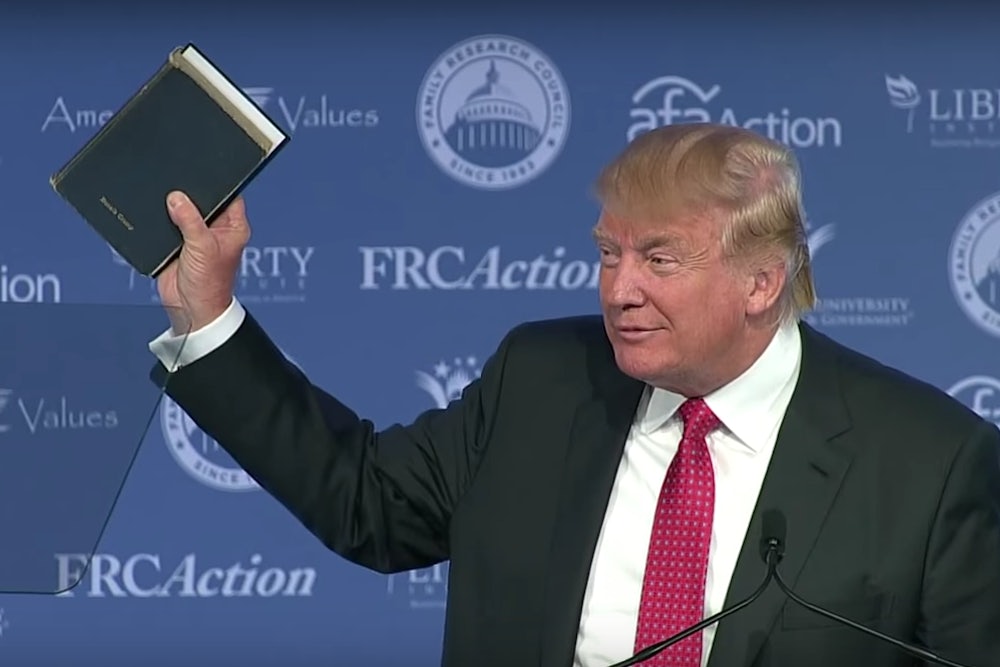

The support that Donald Trump has received from legions of evangelicals has puzzled and “surprised” many people. After all, the presumptive Republican nominee is exceptionally vulgar and, despite claiming to be a devout Christian whose favorite book is the Bible, knows little about scripture and has emphasized, “I don’t like to have to ask for forgiveness” from God. One common explanation for this apparent contradiction is that numerous evangelicals embrace Trump’s agenda, from eviscerating Obamacare to cracking down on undocumented immigrants and barring Muslims from entering America. But Trump and his evangelical supporters think alike in more ways than people realize. Fundamentalist approaches to evangelicalism have long fostered anti-intellectual, anti-rational, black-and-white, and authoritarian mindsets—the very traits that define Trump.

The historian Richard Hofstadter explored the roots of the issue in his 1966 book Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, which described how the spread of evangelicalism since the eighteenth century fostered the notion that education is an obstacle to faith. Not all evangelicals thought alike, although many were convinced that people need not read any book except the Bible. As the influential preacher Dwight L. Moody (1837-99) proclaimed, “I do not read any book, unless it will help me to understand the book.” Hofstadter concluded that this anti-intellectual conception of religion extended to life outside the church. Hardline evangelicals became particularly disdainful of reflection and refined ideas, leading some to be drawn to “men of emotional power or manipulative skill.”

Evangelical traditionalists played a key role in the backlash against Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species (1859), whose theory of evolution exacerbated evangelicals’ skepticism of education and led them to further defy objective evidence and rational thought. Moderate evangelicals warned against this mindset. In a memorable 1922 sermon, Harry Emerson Fosdick, a prominent evangelical pastor based in Manhattan, accused evangelical fundamentalists of making anti-rationalism a litmus test of faith. To Fosdick, fundamentalists were hostile to science and solely accepted thinking that “brings you to certain specified, predetermined conclusions.” “[T]he new knowledge and the old faith had to be blended in a new combination,” Fosdick argued, a process that evangelical fundamentalists resisted and that liberal or moderate Christians accepted.

Leaving aside other factors behind the evolution of evangelicalism, this history helps explain one of the most intriguing dimensions of contemporary America, where approximately a quarter of the population belongs to white evangelical churches. Around 42 percent Americans are creationists who deem that God created humans in their present form 10,000 years ago, and the same proportion expects the prophesied Second Coming of Christ to occur by 2050. No other modern Western democracy has such a huge share of Biblical literalists. Although Americans of diverse denominations hold these beliefs, evangelicals are disproportionately represented among them.

Trump is not an evangelical, yet he too routinely defies rational thought and is unabashedly skeptical of education. While there are numerous reasons behind Trump’s political success, these circumstances shed additional light on why evangelicals have been among the citizens most receptive to Trump’s systematic misinformation. Evangelicals are not only heavily represented among creationists, but also among citizens who perceive climate change as a “hoax,” accept calculated falsehoods about the evils of “socialized medicine,” and think that Obama is a covert Muslim.

Trump’s authoritarianism—the best predictor of his support, by some measures—has found a receptive audience among white evangelicals, who are significantly more authoritarian than mainline Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and non-believers, according to a study by the political scientists Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weiler. The social scientist James Davidson Hunter has also argued that evangelicals emphasize deference to “transcendent authority” based on inflexible conceptions of religion or tradition. Indeed, evangelical traditionalists commonly believe that God will lavishly reward those who obey his commandments while subjecting others to eternal damnation. This authoritarian form of faith translates to other aspects of life, such as the patriarchal authority of the man as the head of the household. There is little doubt that this authoritarian approach to religion is part of the reason why certain evangelicals identify with “strong” leaders like Trump, who makes a show of his toughness, bravado, and machismo.

Needless to say, not all evangelicals support Trump, as many have denounced his impieties, bigotry, and demagogy. But it is revealing that some of Trump’s evangelical critics embraced his now-vanquished rival Ted Cruz. Although Cruz emphasized his fervent evangelicalism to try and differentiate himself from Trump, both share the same anti-intellectual, anti-rational, black-and-white, and authoritarian mindset. Like Trump, Cruz regularly makes extreme declarations and promotes baseless conspiracy theories, as illustrated by his claim that Obama is “the world’s leading financier of radical Islamic terrorism” and that surrendering to “Obamacare” would amount to saying “accept the Nazis.” Cruz even made Frank Gaffney—a conspiracy theorist who has argued that Obama is probably a Muslim—one of his campaign advisors. (According to NBC exit polls, Trump garnered 40 percent of the evangelical vote in the Republican primaries compared to 34 percent for Cruz, as both have dominated the field.)

In recent years, certain evangelical pastors have distanced themselves from hardline approaches to faith. Following the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision recognizing a constitutional right to gay marriage, dozens of evangelical leaders defied orthodoxy by signing a letter supporting the ruling. They included the Reverend Richard Cizik, whose outspoken tolerance led him to be fired as chief lobbyist for the National Association of Evangelicals. Cizik now leads the New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good and works to build relationships between Christians and Muslims, thereby defending a different conception of evangelicalism than those who applauded Trump’s call to ban Muslims from America.

Religions are in constant flux; the evangelicalism of today may not be the evangelicalism of tomorrow. For the time being, however, the support that Trump has enjoyed among evangelicals should puzzle no one.