It is commonly assumed that three straight presidential election defeats are more than either political party can bear before adopting a new policy consensus—and thus that Republicans, after Donald Trump goes down in defeat this November, will soon be welcoming realignment.

Boiled way down, this theory supposedly explains how Bill Clinton took over the Democratic Party and was able to win the presidency twice after three consecutive Republican victories in the 1980s. The country’s political bent was decidedly more conservative than the Democratic Party had been through the Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush presidencies, and by pulling the party to the right, Clinton was able to make it viable with a national electorate once again.

We’ve seen the same basic logic applied to today’s Republican Party since the early days of Barack Obama’s presidency—itself the culmination of two consecutive Democratic landslides. Obama himself hoped that his reelection would, in his words, “break the fever” gripping the Republican Party. When it decidedly did not, he and countless others assumed that a third consecutive presidential election defeat would do what eight years out of power could not.

In theory then, the fact that an obscene figure like Donald Trump was able to overrun the GOP, and is poised to lose the general election overwhelmingly, should herald a massive rethinking of what it means to be a Republican. Trump isn’t the GOP equivalent of Michael Dukakis, personifying a party that has allowed the country to drift away from it. He is a symptom of a broken party—an institution that chose as its standard-bearer a person it considered anathema until recently.

If the three-election theory is correct, it stands to reason that the post-Trump GOP will move to the center in some fashion or another between November of this year and 2020. Either it will adopt the non-profane elements of Trumpism (his economic populism, his restrictive thinking about immigration) and conform to him, or it will abandon different elements of orthodox Republicanism (supply-side economics, white identity politics) and move in a completely new direction.

It is the greatest hope of many Republican professionals, as well as many liberals who believe the GOP has become an extreme and dangerous force in American politics, that the party will reform in some way. Unfortunately, a number of forces—some structural, some unique to Trump’s rise—will resist any change at all, leaving the Republican Party, perhaps for years to come, more broken and unwieldy than ever.

In the wake of Trump, reuniting the GOP under a different paradigm would require at least some existing party factions to reckon with their own shortcomings, and then to adapt or die.

The foreign-policy hawks, religious conservatives, and business toadies of the conservative movement—from whom the #NeverTrump movement draws most of its power—would have to decide whether they could make peace with a Republican Party that wasn’t fully under their spell. The Trumpist wing of the party would, at the very least, have to accept that Trump 1.0 was flawed, if not toxic. And whatever shape the new GOP were to take, the party’s leaders would need to be willing to run it.

The problem is these same stakeholders will also be able to tell stories that disclaim responsibility for the defeat—and they’re rehearsing their lines already.

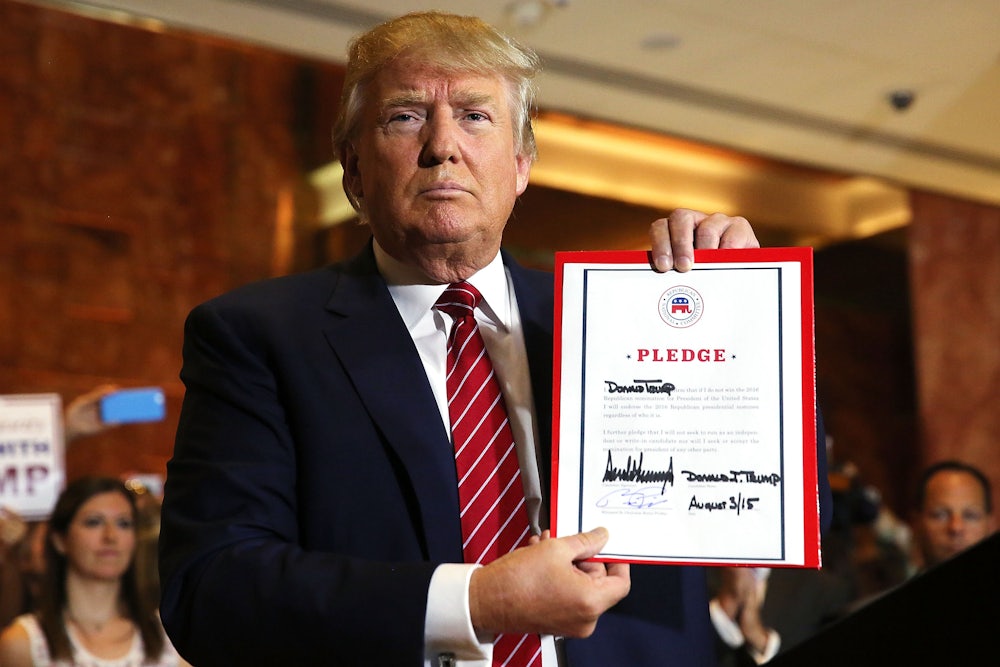

Trump has already proven himself a master of the buck-passing game. Earlier this year, when it seemed that Republicans might be able to wrest the nomination away from him on procedural grounds, Trump laid the foundation for delegitimizing the entire primary process as inherently corrupt; rather than admit defeat, he would argue that victory had been stolen from him. As the primary has given way to the general election, Trump has pre-spun two related defeat narratives, both of which gloss over or ignore his weakness as a general-election candidate.

First, he defines the intransigence of the #NeverTrump right as a threat to Republican victory, and the idea of a third-party candidacy as a suicide mission. “If people want to be smart they should embrace this movement,” Trump said back in March. “If they don’t want to be smart, they should do what they’re doing now and the Republicans will go down to a massive loss.”

In defeat, Trump supporters, following his train of logic, will believe they were stabbed in the back by their own party. They will also believe that they were stabbed in the front by corrupt Democrats.

In recent weeks, Trump has dubbed Clinton “Crooked Hillary”—an epithet optimized to convince his supporters that if he loses, it’ll be because he was robbed. Here, other Republicans, including the anti-Trump wing (in spite of themselves), are abetting him. It is a foundational belief among conservatives of practically all stripes that Clinton deserves to be indicted by the Justice Department for storing state secrets on her personal email server, that an indictment may be coming, and that if it doesn’t come it will be thanks to White House tampering.

Republicans have convinced themselves that Clinton is an unusually weak and eminently beatable candidate—and thus that if she wins, it will be thanks to some dirty trick. It is this presumed weakness that will tempt all factions of the right to rationalize away defeat, and to treat the Clinton presidency as essentially (or actually) illegitimate.

The excuses will fly like gifts from Oprah.

Whether they cotton to a conspiracy theory about the Obama DOJ or not, ideological conservatives will reprise their favorite maxims after the election: that conservatism can’t fail, that it can only be failed, and that in this case it was failed by Trump. Ted Cruz will lead this particular rallying cry. “Any time Republicans nominate a candidate for president who runs as a strong conservative, we win,” Cruz argued in July, and throughout the campaign. “When we nominate a moderate who doesn’t run as a conservative, we lose.”

The Republican establishment—its current and aspiring leaders, its elder statesmen, and those who never warm to Trump but also never disavow him—will meet the Texas senator halfway, writing off Trump as a fluke (a media creation, a celebrity), if not as an outright vindication of Cruz’s wing of the party. “I’m convinced ... many in the press want him to be nominee,” Marco Rubio said of Trump shortly before dropping out of the race. “I think they think it’s going to be good for ratings and ... they know they have a lot of material to work with.”

Thus the GOP of 2017 could be riven along multiple fault lines, unable to agree upon a single story about why Trump happened to them—and parceling blame to one another, along with the Democrats, the media, and other outside forces, but never to themselves. We can expect Republicans to wallow in denial for some time after November. The question is how long. It was only because a consensus emerged among Democrats that the party had to change to win again that it moved right, however painfully, under Bill Clinton’s leadership. Without a similar consensus, a whole new collective-action problem will overtake Republicans, and they will stagger into the next election more heedlessly than they staggered into this one.