In Elena Ferrante’s Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, the narrator, a writer named Elena Greco, has recently given birth to her first child. Elena’s baby becomes “troublesome”: She cries and writhes for hours, and rejects breastfeeding. Elena’s own body rebels against her—she develops a limp, loses her manners, and feels exhausted. Perhaps most distressing, she loses (at least for a time) her ability to write. “I suffered,” she says. “I felt that everything that up to a short time earlier I had taken as an unquestioned condition of life and work was rapidly collapsing around me, as if violently jolted from inaccessible depths.”

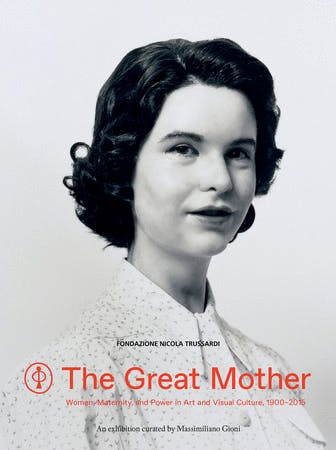

This is something like the conflicted, complicated sense of motherhood at the heart of Massimiliano Gioni’s The Great Mother: Women, Maternity, and Power in Art and Visual Culture, 1900–2015. Published by Rizzoli to coincide with a well-received exhibition Gioni curated at Milan’s Palazzo Reale last fall, the book collects works by artists (male and female) who grappled with changing definitions of motherhood, tradition, and female power throughout the twentieth century. This is not a book filled with sweet, traditional depictions of motherhood; like Ferrante’s narrator, many of the female artists reckon with motherhood as a role that could physically and mentally deter them from creating art. Take, for instance, Méret Oppenheim’s 1931 Votivhild (Würeengel)—in English, “Votive picture (Strangling Angel)”—in which a woman with long, claw-like nails strangles a newborn child. Gioni calls it “the most devastating image of the desire to escape from the suffocation of tradition.” Oppenheim herself described the work as “a sort of talisman to avoid getting pregnant so that she could instead devote herself to art.”

Gioni’s book looks at the ways this conflict has changed over the past hundred or so years, as expressed in works by modern and contemporary artists—including Man Ray, Louise Bourgeois, Cindy Sherman, and Catherine Opie. The excellent reproductions are interspersed with essays by art historians and curators that are sometimes dense and academic in tone, but on subjects fascinating and wide-ranging: Obscure Futurist-feminist manifestos, poems of lust and love, Dadaist machines, and what could be considered a queer reading of Duchamp fill the pages of The Great Mother.

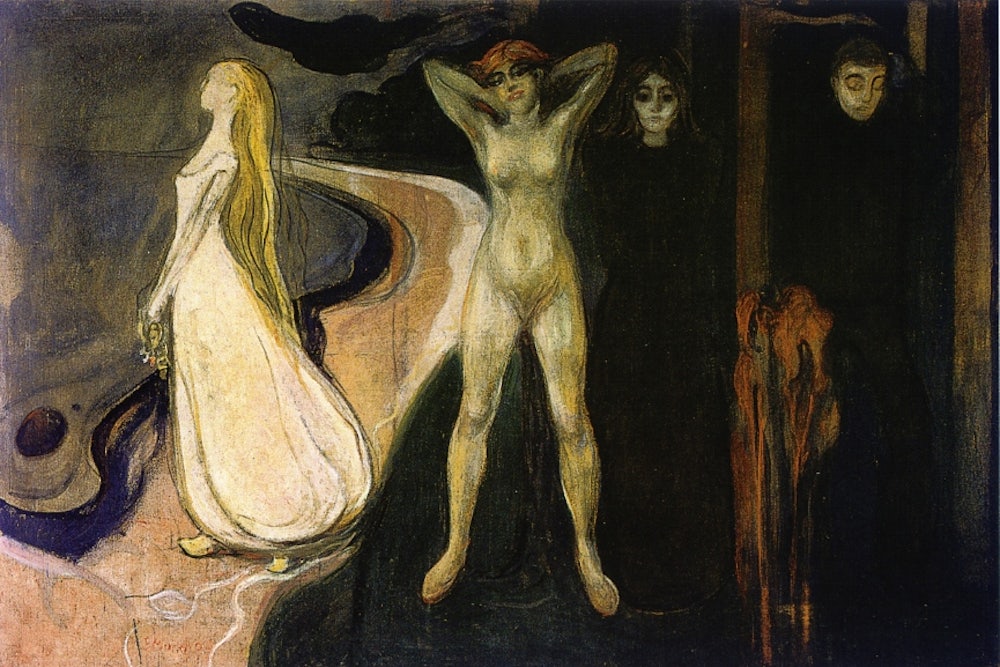

Some might wonder what right a man has to curate an exhibit and book exploring these themes. Last summer, Gioni defended his choice in an interview with Vogue, saying, “I came to the conclusion that I could do it, because if I had not, I would be involuntarily admitting that there is such a division between women and men, and that biology somehow is destiny.” In his introductory essay, Gioni takes Freud to task for claiming “with no embarrassment at the beginning of the twentieth century that anatomy is destiny,” and shows us works by Freud’s contemporaries that both illustrate and subvert that antiquated premise. There is, for instance, Edward Munch’s 1899 lithograph “Woman in Three Stages (Sphinx),” in which three women stand in a line: The first wears a virginal white robe, the second stands frontally nude, and the third wears a somber black dress. The women represent three phases of female life—virginity, sexuality and reproduction, and old age and death—each determined by the woman’s ability to reproduce.

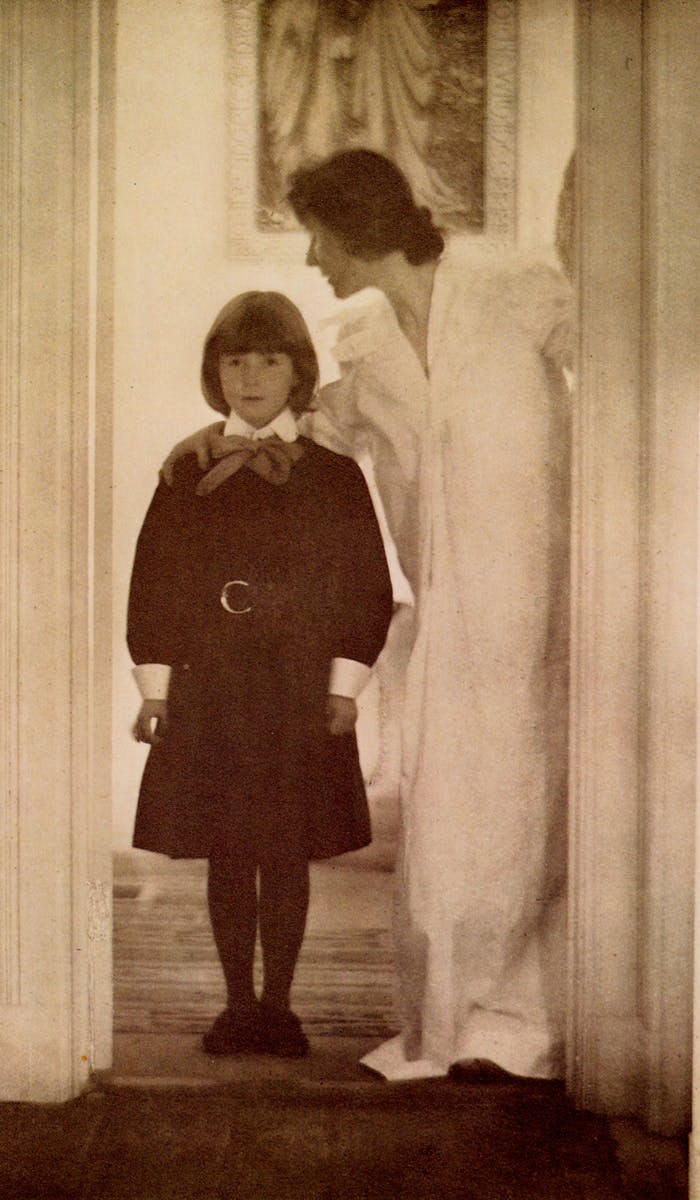

Then there is American photographer Gertrude Käsebier’s 1899 “Blessed Art Thou Among Women,” a black and white portrait of a mother dressed in a long, angelic white dress with an arm around her young daughter. The two stand in a hallway; behind them hangs a religious painting. Light fills the frame, and the pair symbolizes a divine relationship between mother and daughter. As Gioni notes, Käsebier was no straightforward traditionalist: The photograph leaves out a father figure and focuses exclusively on the bond between a mother and her child, suggesting a maternal bond that subverts a conventional, patriarchal vision of the family.

Gioni’s book and exhibition take their title from Berlin-born psychologist Erich Neumann’s 1955 Die Grosse Mutter, or The Great Mother. Neumann’s study—dedicated to his teacher, Carl Jung—traced the development and meaning of the “Great Mother” archetype throughout time, a term, Neumann writes, that refers “not to any concrete image existing in space and time, but to an inward image at work in the human psyche.” In other words, the “Great Mother” is the mother figure of our myths, fantasies, and fears—the woman who can create, nurture, torment, or destroy us.

Many of the figures described and reproduced in Die Grosse Mutter were collected by Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn, an early-twentieth century Dutch scholar of Eastern philosophy and Theosophy. Her collection included Venus, Athena, Diana, Isis, Aphrodite, Demeter, Gaia, Ceres, and Kali, among others—“Great Mother” archetypes that offer a strong visual argument for a history in which women were exalted, worshipped, and all-powerful.

Of course, goddess worship does not translate into gender equality in day-to-day life; you have to consider the role of the real, corporeal female form in these conflicts. Artists’ representations of and regard for the female body changed in fascinating ways over the period covered in the book. Take, for instance, painter, poet, and performer Mina Loy’s 1914 polemic Feminist Manifesto, in which the artist called for “the unconditional surgical destruction of virginity”—an extreme proposal, but one she thought would free women from cultural pressures surrounding virginity, or what she called the “fictitious value of woman as identified with her physical purity.” Later, in the 1930s, German Dadaist Hannah Höch would cut up images of traditional male and female bodies and then collage them back together: babies’ smiles covering men’s faces on women’s bodies and dancing ballerinas’ legs. The physical parts of a person are, in these collages, not essential to their identity.

Come the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, female artists including Louise Bourgeois and Ana Mendieta would return to symbols of goddesses and the natural world. Bodies were organically whole again, or at least less fractured. For Bourgeois this meant round, bulging bronze sculptures, and for Mendieta, “earth-body sculptures,” human silhouette-shaped craters in the earth. The works are sensual and even seem to give off the smell of damp dirt.

The Great Mother is about the power to create: to create art, to create another person, to create oneself. Often, these kinds of creation are at odds—sometimes for reasons similar to the conflicts between motherhood and any job: A person can only have so much energy; there is only so much time in a day.

But Gioni’s book is about another kind

of creation, too: a new matrilineage of female artists across the

twentieth century. In 1980, art critic Lea Vergine curated L’altra metà dell’avanguardia / The

Other Half of the Avant-Garde, 1910–1914, the first Italian art show to

give a history of modern art from a female perspective. Unlike other surveys of

female artists in the 1970s, Vergine’s approach was to present the female

artists as if they belonged in art history all along. “I must say that I

realized…that I had always treated female artists in the same way as males.”

The Great Mother picks up this remit, leaving personal testimony to the artworks. In Rineke Dijkstra’s New Mothers series (1994), young mothers hold their babies soon after they have given birth. The photos are raw and immediate—in one, blood drips down the new mother’s leg. Dijkstra juxtaposes cool, medical lighting and bleak backgrounds with the naked women’s bodies; the women’s facial expressions are proud, scared, and ambivalent. We wonder: Will one of these women share the experience of Elena Ferrante’s narrator?