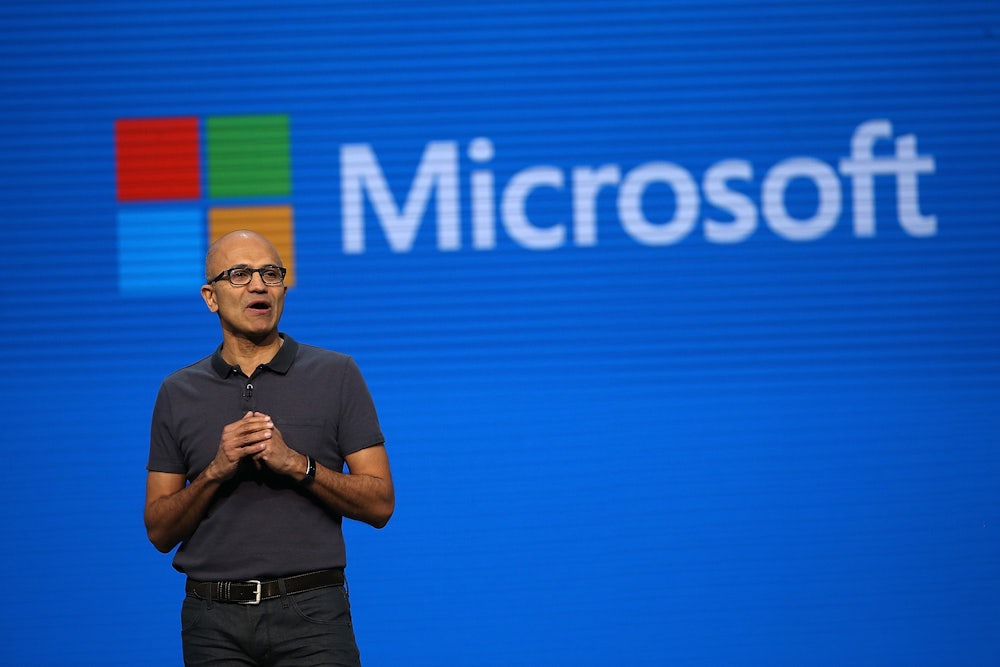

Bots are the new apps. Or at least that was the message from tech giant Microsoft, at their recent developer conference in San Francisco. There, the company suggested that bots, automated bits of software that can understand queries and instructions phrased in everyday language—everything from ordering a pizza to analyzing a database for sales trends—are the next frontier in computing. To that end, Microsoft also announced a toolkit to allow others to build their own bots, simplifying the sophisticated computing necessary to, say, have a customer service issue resolved by an automated bot rather than a person. According to company CEO Satya Nadella, bots may represent as big a technical leap as graphical user interfaces or apps on smartphones.

Whether that’s true remains to be seen. Facebook, however, is throwing its considerable weight behind bots in Messenger; 20 million people in China are already chatting with Xiaoice, a bot developed by Microsoft. (On Weibo, the popular Chinese micro-blogging service, it’s currently ranked the service’s most influential user.) Slack is investing $80 million into bots for its own popular chat app, while everyone from startup studio Betaworks to former Engadget editor-in-chief Ryan Block is involved in creating or funding bot startups. It’s clear that we’re about to hear a lot about them.

Bots promise convenience. They’ll be found in chat apps, where we’ll talk to them as we do with our friends, and they’ll be there when we need help, like a modern Clippy—but for everything. They’ll be more sophisticated, though, and far more useful. Today we expect a lot more from our digital assistants: not just rote answers, but intelligent responses—though at the moment the actual efficacy of bots seems to be middling at best.

Our desire for them to get better, however, remains. Bots are supposed to make things like scheduling appointments or booking flights as simple as asking the question. We want them to be Siri on steroids, to make everyday tasks automatic. The ultimate aim, though—at least according to Microsoft’s Nadella—is to produce a kind of “ambient intelligence.” Think less a series of automated tools, and more like a smart, constantly available assistant. We want to ask our bots, “What is good around here?” or, “How should I organize my day?” and get useful answers. Imagine being able to ask your Netflix bot to “show me a sad movie I would like” or request Amazon’s Alexa to “play the perfect song for a sunny morning.”

More than anything, bots promise us a release from the contemporary tyranny of choice. While many would of course cringe at the idea of outsourcing taste to an algorithm—not to mention the worries about privacy, or the way algorithms can enforce their own authority on the world—the allure is nonetheless clear: In a world of infinite choice, our bots could free us from freedom.

The digital age is designed to maximize options: The technology that powers bots comes from the same impulse as the tech that makes it easy to read hundreds of news stories, have access to millions of songs and thousands of movies, and endless information and entertainment. What makes bots practical at this juncture in history is also what makes them compelling: they can wade through the muck that we don’t have the energy or time for. Siri, it’s all too much! Just tell me what do. Technology has filled modern life with more data than any one human can possibly manage or understand, and bots are ideal filters.

Right now, the best example of how bots might work is the Quartz news app—which, both fittingly and funnily, is not a bot at all. Human editors write and curate the information. Instead of delivering the day’s stories on a web page, the app chats with you. The experience is like messaging an informative, know-it-all friend. That might sound odd, but it’s surprisingly compelling, in no small part because of the friendly, approachable way it the app commands your attention.

The Quartz app—and the bots that inspire it—works because someone else takes the wheel. (Perhaps we’re too drunk on data to drive?) Writing about Tinder, New Inquiry editor Rob Horning said that the dating app “automates the process of finding someone but not what [to] do with them afterward.” The thought is applicable to situations outside of dating: While bots can automate life, you still have to live it.

Perhaps that’s why I find the True Love Tinder Robot so appealing. The “robot” is in fact a few sheets of metal you touch that measures your galvanic skin response—basically the change in how electrically conductive your skin is—and a robotic hand, controlled by an Arduino board, that swipes left or right on Tinder accordingly. (Its creator, New York University graduate student Nicole He, wrote that she created the robot to consider what happens when we combine algorithms and biometric devices.)

That robot literally makes swiping automatic—or perhaps autonomic. In the face of an endless-seeming sea of possibility, the Tinder bot perhaps explains what we want from bots, in general, as well: ceding our ability to choose because we have too much choice.