In the opening swath of the last century, if a writer was luckless enough to arouse the disapproval of D.H. Lawrence, he could usually expect a poison-pen letter of soul-stomping vitriol. Trenchantly idealistic about literature—is there any other way to be for the artist and critic?—Lawrence had a talent for combining a maximum of good taste with a minimum of good tact. His 1923 book Studies in Classic American Literature remains a necessary take on our canon, and his essays and reviews come close to the songful discernment of Oscar Wilde’s, but you must turn to his letters if you want the undiluted Lawrence, the venom behind the vision.

To poet Amy Lowell in 1914: “Why do you deny the bitterness in your nature, when you write poetry? Why do you take a pose? It causes you always to shirk your issues, and find a banal resolution at the end.” To Katherine Mansfield in 1920: “I loathe you. You revolt me stewing in your consumption,” to which he amends this barb: “The Italians were quite right to have nothing to do with you.” To critic John Middleton Murry in 1924: “Your articles in the Adelphi always annoy me. Why care so much about your own fishiness or fleshiness? Why make it so important? Can’t you focus yourself outside yourself? Not forever focused on yourself, ad nauseam?” To Aldous Huxley in 1928: “I have read Point Counter Point with a heart sinking through my boot soles. … It becomes of a phantasmal boredom and produces ultimately inertia, inertia, inertia and final atrophy of the feelings.”

This is to philosopher Bertrand Russell in 1915: “You simply don’t speak the truth, you simply are not sincere. The article you send me is a plausible lie, and I hate it. If it says some true things, that is not the point. The fact is that you, in the Essay, are all the time a lie.” It gets worse from there:

I would rather have the German soldiers with their rapine and cruelty, than you with your words of goodness. It is the falsity I can’t bear. I wouldn’t care if you were six times a murderer, so long as you said to yourself, “I am this.” The enemy of all mankind, you are, full of the lust of enmity. It is not the hatred of falsehood which inspires you. It is the hatred of people, of flesh and blood. It is a perverted, mental blood-lust. Why don’t you own it.

“Misanthropist” was a boomerang Lawrence probably should have kept holstered. His collected letters make clear that he cared for ideas and art far more than he cared for people: “I am so weary of mankind,” he wrote to E.M. Forster in 1916. In person, Lawrence could be as churlish and base as any bitter genius, but his particular appetite for insult seems to have been activated around stationery. There’s a whole continent between what you will say in person and what you will say on paper. The above targets were Lawrence’s friends, so just imagine the letter you got—the missive as missile—if you were his foe. He ends the note to Russell: “Let us become strangers again. I think it is better.”

Literary ethos has always thrived on such writer-to-writer invective, especially in Britain, where Alexander Pope could ruin you with a couplet. When the criminally overrated novelist Hugh Walpole sent Rebecca West a self-pitying letter complaining about West’s treatment of him in the papers, she replied with typically Westian bite: “I don’t like your work; I think it facile and without artistic impulse,” and then dished him a much-needed lesson on “the duty of a critic to point out the fallaciousness of the method and vision of a writer who was being swallowed whole by the British public, as you are!”

With the spread of mass literacy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that public began scribbling to authors as never before. If you had to guess which nineteenth-century author received the most mail, guess Charles Dickens. In November of 1840, as The Old Curiosity Shop was being serialized, he groaned: “I am inundated with imploring letters recommending poor little Nell to mercy.” Dickens’s ferocious popularity coincided not only with rising literacy rates but with the Uniform Penny Post, the overhaul to the Royal Mail that allotted cheap postal access to the British public. You can imagine the aching back of Dickens’s mailman, and you can imagine that where there’s fan mail, there’s hate mail. Dickens destroyed almost all of the letters he received from readers, but Mark Twain didn’t, and in Dear Mark Twain: Letters From His Readers, you’ll see the baffling goulash of mail people felt compelled to send him. As the foreword has it, these missives came from “farmers, schoolteachers, and schoolchildren, businessmen, preachers, customs agents, inmates of mental institutions, con artists, dreamers of various sorts, and at least one former president,” all of them witness to the first American movement of mass education, the first time in history the nation had a mass readership.

They asked Twain for autographs, for advice, for aid in publishing their own work; they begged for money; they offered approbation and they offered scorn. From one gentleman in 1880: “What I want to know is by what rule a fellow can infallibly judge when you are lying and when you are telling the truth. I write this in case you intend to afflict an innocent and unoffending public with any more such works.” From an Ohioan in 1885: “Dear Sir: For Gods sake give a suffering public a rest on your labored wit.—Shoot your trash & quit it.—You are only an imitator of Artemas Ward & a sickening one at that & we are all sick of you, For Gods sake take a tumble & give U.S. a rest.” (That’s Artemus Ward the humorist and irreverent lecturer, nom de plume of Charles Farrar Browne.) You can almost feel the cozy glow of smugness in those lines, their self-satisfied warmth, the underlining current of What makes you so special? Every hate mailer is charmlessly convinced he knows best, certain his standards beat the author’s. That Ohioan obviously got a good deal of pleasure from unloading on Mark Twain, and that seems to be nine-tenths of the reason people bother to send hate mail: It cheers them up.

In his 1826 essay “On the Pleasure of Hating,” William Hazlitt speaks of our rueful inability to “part with the essence or principle of hostility,” and of hatred being “the very spring and thought of action.” Hazlitt’s thesis—he would have found kin in Lawrence—is that the joy of hate is intrinsic to our cantankerous tribe. “Love turns, with a little indulgence, to indifference or disgust: Hatred alone is immortal.” We might have been civilized enough “to give up the external demonstration, the brute violence,” but the urge to such violence throbs in us still. We won’t club an author over the head, but we’ll mail him a nasty note and grin as we do. Before the imperium of the internet, there was a pleasing ritual involved: The hate mailer had to put pen to pad, choose the envelope and stamp, unearth the address of the publication in which the offense appeared, then walk down the block to the mailbox. It was a personal affair, from the hater’s hand to the author’s. And the chances were high that the author would read the letter, too. Remember when you used to get letters in the mail? You always read them. Now the hate mailer’s slap is only a click away from reaching your face, but also only a click away from being deleted unread. Gone is the pleasure of the personal.

In More Die of Heartbreak, Saul Bellow’s narrator remarks: “There’s no having any relations with people; none at all, if you won’t accept abuse.” A writer has a kind of relationship with his public, with both the brains and the boobs that comprise it. Should you become a writer, brace yourself for the analphabetic rantings of the anonymous, the frivolous, the platitudinous and crapulous. Prepare for a cataract of derision and self-righteousness should you dare pen anything perceived as too left or too right, as too pious or too profane, as possibly ageist or racist, sexist or classist, each “ist” word shot like a silver bullet intended first to take you down and then to wake you from your own beastliness. Of course it doesn’t matter whether you are any of those things, or even if your record or your prose indicates the opposite—only that you are perceived as such.

When several reviews of my second novel compared it to Cormac McCarthy’s work, I published an essay suggesting that the book’s bloodshed had a provenance that predates McCarthy, an essay that starts with a synopsis of Harold Bloom’s theory of the anxiety of influence and that in no way disparages McCarthy’s tremendous achievements. In response, I received this message from an incensed gentleman, the subject line of which was, “Your simplistic attack on Cormac McCarthy”: “Your book says nothing, nothing, because you have nothing to say. At 3:00 a.m. I was rereading McCarthy’s The Crossing and saying thank you thank you to be in the hands of a master.”

A Midwestern professor emeritus once wrote to reprimand me for saying how much of Freud is first-rate babble: His logic was that as a novelist, I didn’t have the right to comment on the great doctor. Here’s a message to me from “Odette de Crécy,” the Parisian courtesan in Proust’s grand novel: “You should have recused yourself from reviewing ——— by ——— in the Times last Sunday on the basis of simply not understanding it enough to be able to review it on the novel [sic] terms and not yours.” You’d think that a character out of Proust would have a better grasp of the pas de deux between critic and novel: All the critic has are his own terms.

Some hateful messages I’ve received don’t convulse beyond the few words in their subject lines: “Drop dead” or “Go to hell.” Others are so epically effusive you could scroll for an hour and still see no end to them. Some are vulgar without charisma, while others are inscrutably dull. (Go to YouTube to see the comical clips of Richard Dawkins reading his vulgar hate mail from Christians.) And then there’s the kind of hate mail that achieves its effects not through any specific slur in any one message, but through sheer electronic blitzkrieg—as with the gentleman who sends me six emails a day, every day, each with a link to data “proving” the existence of UFOs, and this because I made, in an otherwise affectionate piece on The X-Files, an entirely reasonable pronouncement about the stupidity of believing in UFOs, never mind in alien abduction.

Of course hate mailers can’t be relied on for propriety, but many of them choose to forgo salutations, as if to declare that you aren’t worthy of one, even though you were somehow worthy of being written to in the first place. Many will nix the “Dear”—you are not dear to them—and begin only with the clerical thud of your full name, followed not by the more comely comma but by the two fang marks of a colon. They dump their radiant glumness upon you and then don’t even bother to sign their names. The gist common to all my hate mail is not only that I’m stupendously wrong in whatever view I’ve espoused—hate mailers have a qualmless relationship with right and wrong—but that I don’t deserve the honor of espousing such views, of inflicting them upon minds that wish to remain undefiled by someone else’s ideas. The tenor of their hate is always: How the hell did you get hired?

And that’s something else I can’t help but notice: Many hate mailers are clearly themselves writers, aspiring or frustrated or homicidally disappointed—as with the person who didn’t like one of my essays and so wrote to tell me that he was no longer submitting his work to the literary journal for which I’m an editor. (He also added the punitive mantra of hate mailers everywhere: “Cancel my subscription.” When William F. Buckley published a collection of his replies to piqued readers of National Review, he called it Cancel Your Own Goddam Subscription.) So although their ire is aimed at you and whatever you wrote that set them off, the real target of that ire, I suspect, is the publishing business itself, the gatekeepers who won’t let them through. I can empathize: No matter where a writer is in his career, there are always gates he can’t get through.

Suffering from terminal neglect and the infertility of his wrath, the hate mailer wants your attention, and so the unkindest thing you can do is not to cut him down in a reply, but to deny him the rumble or rumba he’s come looking for—never write back. You can’t quarrel with inanity; it makes more sense than you do. What’s worse, hate mailers are all too often humor-impaired, and is it me, or do the humor-impaired have a badly skewed picture of what’s happening in the world? One wishes for wiser, funnier detractors, worthier adversaries.

As someone who doesn’t send hateful mail to strangers, I’m left wondering about the precise motivations of those who do. What do they want exactly? It can’t be simply to cheer themselves up, to scold, or to convince you of your erroneous ways. The likes of a Lawrence or a West had a hard-won ars poetica to assert and defend, but for today’s average hate mailer, something else is going on. The political and cultural critic Steve Almond has written recently about his horde of haters:

These letters, as I came to see it, represented an unedited transcript of America’s seething id. Not the airbrushed insinuation retailed by Fox News, but the monstrous grievance roiling within its viewers. … The wrath directed at me was the logical byproduct of media devoted to monetizing the defensive rage of culturally dislocated citizens. … I continue to find the hate mail I elicit—along with the jeremiads that reside in the comments sections of online pieces—deeply compelling. They are one of the few spaces in our ideologically self-segregated culture where echo chambers collide. These outbursts, as repugnant as they can seem, often feel more authentic than the reasoned arguments we recite to those who already agree with us.

Almond’s is an incisive and merciful take, though what he sees as echo chambers are more frequently torture chambers. Even the kindest comments section is a petri dish of jaundice. What purpose could these sections possibly serve? For those venues sustained by advertising, the manic nuttiness keeps your eyes on the page for that much longer—we enjoy watching others in a conniption as they attempt to type. For other venues, the comments section functions as a kind of welcome mat, an invitation to inclusion through dialogue. But the inclusion is illusion, because the dialogue is one diatribe after another. “Conversation,” often with “honest” or “adult” tacked on to it, has become the preferred euphemism of those who seek to holler their opinions at you. (Kingsley Amis once quipped that you could normally count on the phrase “meaningful dialogue” being uttered by “a humorless ninny.”)

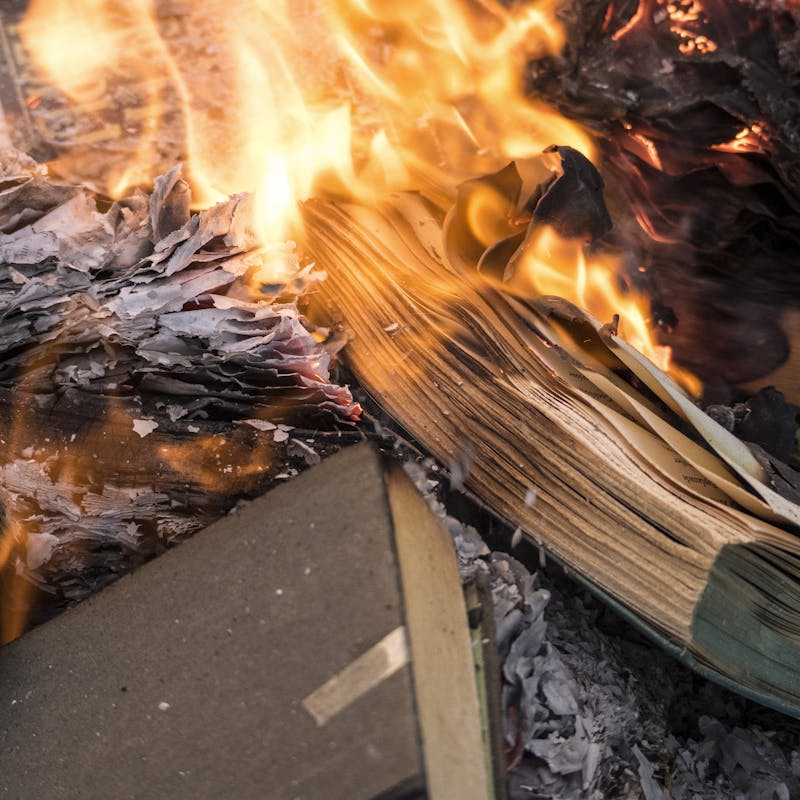

With the online comments section, hate mail, like everything else, has gone public, and mostly anonymous. The internet, says Almond, facilitated “the rapid erosion of the barrier between private animus and public expression,” and that’s well put. Writers have always earned hatred from certain readers: If you were Ovid, that hatred got you banished from Rome; if Giordano Bruno, incinerated at the stake; if Flannery O’Connor, a scrawled shellacking from some unhappy Baptist in Georgia. In our sound-biting society of obliterated attention spans, you get blasphemed online, or else in your inbox—instantaneously, by any mosquito with a keyboard. The internet didn’t create hatred but, true to its name, the internet caught it. It’s the modus operandi of online yokels to be outraged, every few minutes, by some trifle or another, to traffic in “the nothingness of scorn and noise,” in John Clare’s immortal wording. Their general confusion of rhetoric for logic and rationalization for reasoning is not merely their limit but a fairly damning limitation. Users are fleeing Twitter in packs, and its stock lies at the bottom of an open grave, and not only because of its restrictive platform, but because it’s been from the start an engine of acrimony.

People are desperate to be heard, to make some sound, any sound, in the world, and hate mail allows them the illusion of doing so. Legions among us suffer from the anomie and malaise of modernity, from the discontents of an increasingly atomized society. Almond’s mercy for his correspondents, even for those who wish him harm—one beauty calls for his beheading—is not a cynical emulation of Christ, but a measured awareness that people are rotten because they’re wounded, lashing out in search of succor. The democratizing splendors of the internet, the equalizing of voices? Another illusion. If ideas were being heard in substantive, bountiful ways, online comments sections wouldn’t be so impulsively rancorous. The new hatred has a terrified undercurrent: the dread of disappearing beneath the ceaseless waves of dissonance.

For writers in our culture, marginalized and irrelevant, hate mail at least means that someone is listening, even if with unfriendly ears. A mentor, a well-known critic who himself has been subjected to the quiverings of hate mail, said to me recently: “But you’re a little disappointed when you don’t get it, aren’t you?” And I had to confess that I was. Part of a writer’s job should be to dishearten the happily deceived, to quash the misconceptions of the pharisaical, to lure the hermetic from whatever bolt-holes they’ve built for themselves—to unsettle and upset. If someone isn’t riled by what you write, you aren’t writing truthfully enough. Hate mail is what happens when you do.