When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced the Black Panther in the pages of Fantastic Four No. 52 in 1966, they were wholly unaware that the Lowndes County Freedom Organization—an Alabama-based civil rights group organized by Stokely Carmichael that had broken away from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which had for years organized sit-ins and freedom rides across the South—used the animal as their totem. Lee and Kirby’s Panther was a singular icon, the hereditary ruler of the fictional African nation of Wakanda. Under the banner of its own panther, the LCFO rejected Dr. King’s call for nonviolence in favor of armed resistance, and their methods inspired Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in California as they established the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in the fall of 1966.

Despite what Lee would come to view as an unfortunate coincidence—the Black Panther was briefly known as the “Black Leopard” to avoid comparison to the militant civil rights group—Lee and Kirby were working through questions of representation. Two issues prior to the Black Panther’s appearance, the duo introduced a Native American character, Wyatt Wingfoot, as Johnny Storm’s college roommate; Fantastic Four No. 45 featured the debut of the Inhumans, a mysterious, genetically advanced race living in a hidden city in the Himalayas—essentially Asiatic others. The Black Panther—whose given name is T’Challa, son of T’Chaka—seemed like another iteration of this trend, a distinctive character dreamed up by a creative team deeply invested in the liberal politics of cold war America.

By introducing and promoting the Black Panther in the pages of Fantastic Four, one of its top-selling series, and then adding him to The Avengers in 1968, Marvel sought to market him to a wide audience. Readers found the Black Panther so appealing that he endures 50 years later, when other characters introduced during the same period—try to find a Wonder Man comic—have largely been forgotten. While tragic violence and the fracturing of the New Left have come to characterize the last years of the 1960s, those events went largely unremarked in the Marvel universe, despite the presence of cosmopolitan figures like T’Challa and the company’s penchant for incorporating the issues of the time into its books. Indeed, Marvel addressed the politics of the day more often during the Nixon presidency, which saw Spider-Man confront Students for a Democratic Society activists in 1969 at Empire State University—a fictionalized Columbia University—and Captain America abandon his mission as protector of the United States to become Nomad, the man without a country.

During this period, the Black Panther engaged with questions of race and sovereignty in Fantastic Four No. 119, perhaps his most important early story. Written by Roy Thomas, it opens with T’Challa imprisoned in the Republic of Rudyarda, a stand-in for apartheid South Africa. The issue occasions, as far as I can tell, the first use of the phrase “white supremacy” in a Marvel comic, but it also establishes a central template for T’Challa’s character: the tension between his duties as a head of state and his responsibilities to the heroic community. After the 1960s, the writers charged with chronicling T’Challa’s adventures—most notably Don McGregor, Christopher Priest, the filmmaker Reginald Hudlin, and, recently, Jonathan Hickman—continued to address politics within the parameters established by Thomas.

Thanks to their efforts, the Black Panther gradually became a central part of Marvel’s universe, essential to narratives surrounding not only the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, but also Daredevil and Captain America. As befits the first hero of African descent published by a major comic book publisher, T’Challa interacts in significant ways with all of Marvel’s other black characters—from the Falcon to Luke Cage to Storm—and they derive inspiration from his stewardship of Wakanda, a truly independent African state that also happens to be the most advanced nation on earth. Marvel’s original rhetoric about Wakanda—unconquered by Western powers and thus untainted by neocolonialism—resembled African American discourse about Haiti in the 1850s and Ethiopia in the mid-1930s, which helps explain T’Challa’s appeal to a post-Civil Rights cohort of black Americans.

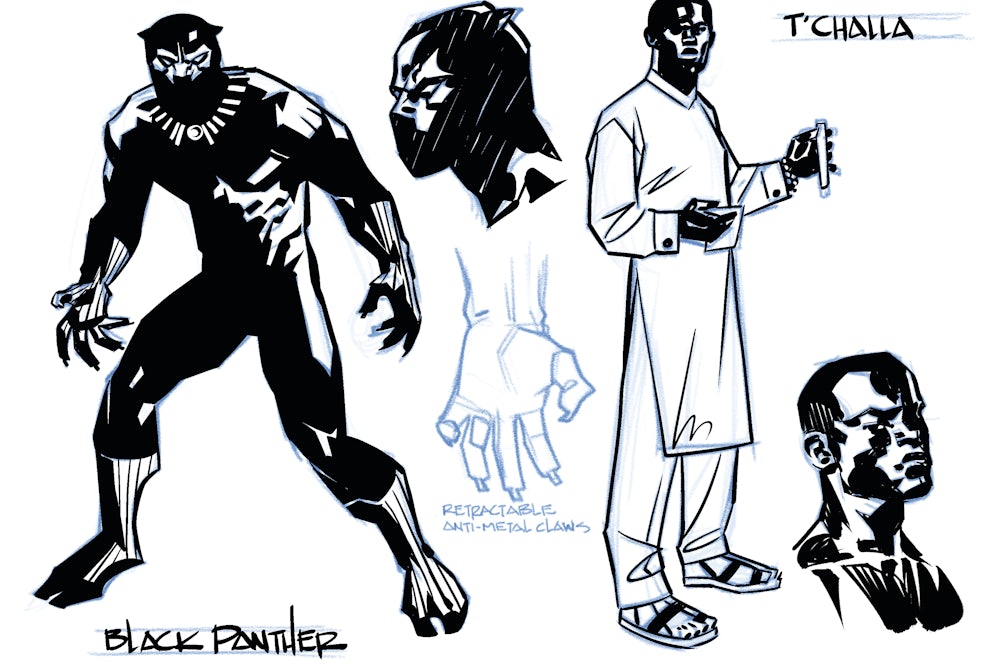

The rebooted Black Panther series engages with this shared history in important ways. The first story arc of twelve issues is titled “A Nation Under Our Feet,” after Steven Hahn’s Pulitzer Prize-winning history, which recounts how African Americans in the South struggled to gain political power after the Civil War. Written by journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates and illustrated by Brian Stelfreeze, it promises to introduce the Black Panther to a much larger and more diverse readership than he has previously enjoyed.

Under the guidance of editor-in-chief Axel Alonso, Marvel has successfully launched a number of books featuring underrepresented characters over the last several years, including an Afro-Latino Spider-Man, a female Thor, and a Pakistani-American Ms. Marvel. Indeed, prior to Black Panther’s record-breaking debut in early April—the first issue sold through a 350,000 initial print run and has gone into a second printing—Ms. Marvel was Marvel’s top-selling comic. It speaks to the cultural capital of the comic industry in general and Marvel in particular that Coates, perhaps the most prominent contemporary writer on race and its role in American history, was interested in working for the company. He is not alone in this; in recent years, Marvel, DC, and Image have invited Hollywood creators (such as Hudlin, Kevin Smith, and Joss Whedon), novelists (such as Marjorie Liu and Greg Rucka), and journalists (such as Coates and G. Willow Wilson) to create comics for them. These outsiders are often tapped to write diverse characters, as with the Muslim American Wilson’s work on Ms. Marvel.

Coates originally pitched Alonso about writing Spider-Man, but it makes sense that Black Panther is Coates’s first foray into comics; his father was once the chairman of the Maryland chapter of the Black Panther Party. And as a lifelong fan of Marvel comics, Coates is as well-versed in its fictive history as he is in America’s bloody past. A writer of immense talent and intense ambition, whose work is distinguished by its ability to connect policy outcomes to the inner lives of individuals, Coates brings unique insight to the comic book form. He does not, as his critics would have it, minister to white guilt—Coates would have hemorrhaged readers of color long ago if that were the case—so much as he models a principled and searching intellectual practice, even while grappling with questions of power and inequality that have bedeviled generations of American writers. Coates’s reluctance to offer easy solutions is part of his appeal, and it’s ideal for comics—a form that chronicles a never-ending series of conflicts. Coates has found an able collaborator in Stelfreeze, who renders the fantastical world of Wakanda tangible without losing its pathos.

Working with established superheroes places particular demands on a writer, as it involves two kinds of collaboration: An author works with an illustrator to tell a story, but the author must also build upon what earlier creative teams have established about the character. In this sense, writing a comic about a long-standing protagonist like the Black Panther—or Batman or Spider-Man—involves reconfiguring story lines written by legends like Stan Lee or Jack Kirby, as well as by less-heralded creators, into a new narrative.

There are two ways for a writer to do this. You could bring to the surface the essential traits of your character in a way that allows readers to experience these familiar qualities anew, as Frank Miller did for Batman with The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and Batman: Year One (1987), and Grant Morrison achieved with All-Star Superman (2008). The other approach is more subtle: Reread your character’s archive, gently realign his portrayal by attending to heretofore overlooked elements, and simultaneously create new supporting characters who facilitate the new direction. Alan Moore pioneered this approach with his run on Saga of the Swamp Thing from 1984-87, and Matt Fraction successfully reinvigorated the characters Iron Fist (2006-09) and Hawkeye (2012-15) using this method. Though the writer changes the character’s canon, the new iteration, if successful, supersedes the old while opening new avenues for storytelling. Coates takes the latter, more challenging approach and, based on my reading of the premiere issue along with the scripts of the first four issues, his Black Panther series succeeds wonderfully.

Coates renders the Black Panther as a reluctant king at the outset of “A Nation Under Our Feet,” which is a dramatic change. Comic fans have always accepted T’Challa’s serial absences from Wakanda as a consequence of the narrative logic of the Marvel universe, which locates all its heroes in and around New York City. An earlier Black Panther series, for example, opens with T’Challa arriving in New York alongside the Wakandan U.N. delegation, but then maneuvers him to Brooklyn, where he lives in a tenement and tussles with drug dealers who are using a Wakandan foundation to launder their profits. Despite these occurrences, earlier writers insisted that the Black Panther took his responsibilities as sovereign seriously.

Coates, on the other hand, reads that narrative as a sign of T’Challa’s reluctance to accept the responsibilities of the crown, and builds his characterization around it. Considering Coates’s assessment of Queen Nzinga, a seventeenth-century ruler of present-day Angola, in his last book—he identified most with her adviser, “who’d been broken down into a chair so that a queen … could sit”—it is unsurprising that he would chafe at writing a character who uncritically accepts his suitability to rule a nation. But Coates does more than simply reveal T’Challa’s self-doubt. In a recent New York Times discussion of the comic, he approaches the question of Wakandan governance from a different angle, wondering why Wakanda’s “educated population” would “even accept a monarchy.” The initial chapters of Coates’s Black Panther suggest democratic reform is in the offing, a radical change to the Wakandan status quo that allows Coates to interrogate the republican tradition Western readers often take for granted. In past iterations of Black Panther, those who worked to undermine dynastic rule were ultimately revealed to be either usurpers who craved the power of the throne for themselves, pawns controlled by Western powers seeking to undermine the only truly independent African nation so that they might exploit its natural resources, or both, which positioned the benevolent Wakandan monarchy as the foil for neoliberal entanglements.

While some elements of this international intrigue remain in “A Nation Under Our Feet,” Coates legitimizes at least some of the voices decrying monarchical rule. Indeed, perhaps Coates’s most intriguing new character, Zenzi, throws Wakanda into crisis by bringing the citizenry’s conflicted feelings toward T’Challa to the fore. She promises to be a formidable political foe, though the narrative hints she might evolve into an ally, depending on how the “Wakandan Spring” develops.

If superhero comics—with the notable exception of Chris Claremont’s 17-year run on X-Men—have traditionally devoted themselves to presenting the stories of heroic men, Coates works to correct this imbalance. Aside from Black Panther’s titular character, Coates allots most of his attention to female protagonists: the aforementioned Zenzi; T’Challa’s stepmother and regent, Ramonda; and Ayo and Aneka, members of the elite, all-woman Dora Milaje, which functions as Wakanda’s secret service. Coates’s Ramonda works to balance her role as trusted adviser to the king with her own instincts as a politician and her maternal concern for her son. Ayo and Aneka are both soldiers and lovers, which violates the tradition that demands the Dora Milaje remain chaste while in the service of the Black Panther. Their relationship allows Coates to reveal the gendered violence and subordination present in even the most enlightened nation—the couple flee the palace to escape royal censure—but also frees him to address problems the patriarchal royal family has overlooked. Even in Wakanda, women’s problems receive less attention from the state. Within four issues, Coates establishes each of these women as complex characters with distinct motivations, even as he hints at the reintroduction of another important female character, T’Challa’s sister Zuri. While Zuri died protecting Wakanda in T’Challa’s absence, loyal comic readers know that death is rarely permanent.

One of the most persistent critiques of Between the World and Me, Coates’s most recent book, was that it paid insufficient attention to the ways that black women confront racial violence. His work here suggests he’s taken this critique to heart. (Coates even recently posted on his blog at The Atlantic about his enthusiasm for crafting the “feminists of Wakanda.”) Given the dearth of black women in comics—X-Men’s Storm remains the most prominent black woman in the medium, decades after her debut—Coates’s interest in female subjectivity is a most welcome change.

Coates’s narrative contains a number of moving parts, which may make for tough sledding for those unfamiliar with comics as he works to set the stage; the whirl of characters can become bewildering. Issues 3 and 4 are more measured, and demonstrate Coates’s increasing command of the form. While it remains to be seen what he does with the remaining issues in “A Nation Under Our Feet,” the initial story arc is compelling. Coates’s interrogations of sovereignty seem particularly relevant, given the Republican Party’s largely successful attempt to blunt President Obama’s policies by violating the norms of governance—to say nothing of the farce that is Donald Trump’s front-running candidacy. Coates critiques the Black Panther’s tendency to resort to force to resolve conflicts, which mirrors the larger conversation about state-sanctioned violence instituted by Black Lives Matter. Coates balances action and exposition expertly throughout these first four issues, though his more ruminative moments remain most compelling. After his virtuosic blending of poetry into the comic form I’m curious to see him branch into more meditative indie comics. There are moments that suggest he might prove an equal to creators like Alison Bechdel (Fun Home) or Daniel Clowes (Ghost World).

Coates has committed to writing Black Panther for the next few years, and watching a son of the Black Panther Party take the Black Panther to new heights promises to be a thrilling experience. Despite the comic industry’s recent willingness to employ outside talent, that Coates—National Book Award winner, MacArthur fellow—now works at Marvel represents quite a coup. Comic companies have never employed a writer of such renown, a public intellectual who has sold millions of books, his work omnipresent on college syllabi and translated into several languages.

Given the confluence of events—the last year of the Obama presidency, the ongoing Black Lives Matter protest movement, the fiftieth anniversary of the character—one expects we’ll never see a moment like this again. Pay attention to Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Black Panther. History will either mark it as an interesting detour in an important career, or herald it as a new peak for comics.