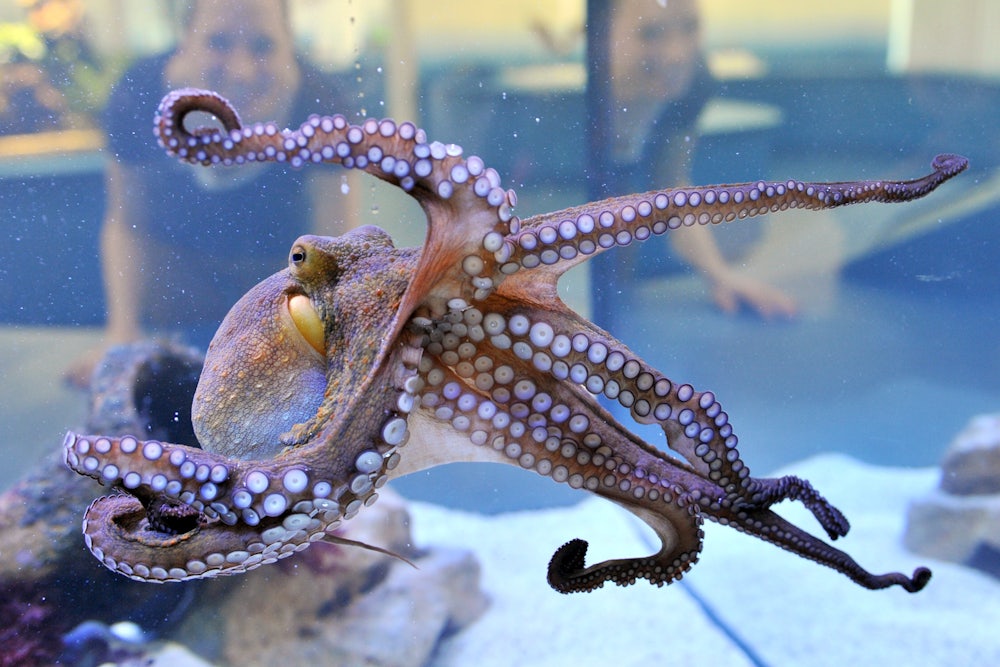

Inky the wild octopus has escaped from the New Zealand National Aquarium. Apparently, he made it out of a small opening in his tank, and suction cup prints indicate he found his way to a drain pipe that emptied to the ocean.

Nice job Inky. Your courage gives us the chance to reflect on just how smart cephalopods really are. In fact, they are real smart. Octopus expert Jennifer Mather spent years studying them and found that they not only display the capacity to learn many features of their environment, they will transition from exploration to something approaching play if given the chance.

For example, Mather recounts the way two octopuses repeatedly used their water jets to blow an object towards an opposing stream of water in their tank: what she describes as “the aquatic equivalent of bouncing a ball”. Further, as Mather explains, cephalopods are inventive problem solvers. When predating clams, for example, octopuses will use a variety of strategies to remove the meat from the shell, often cycling through strategies—pulling the shell open, chipping the shell’s margin, or drilling through the shell—in a trial-and-error way.

It’s not just cephalopods, of course: lots of non-humans are intelligent too. In their own kind of way, lots of machines are smart as well—some are better than the best humans at some of our most complicated games. You can probably sense the question coming next. Does this mean lots of non-humans—octopuses, crows, monkeys, machines—are conscious? And if so, what do we do about that?

Such questions are attracting a lot of interest. In the past month alone, leading primatologist Franz de Waal has written on anthropomorphism and consciousness in chimpanzees; philosophers and science writers have discussed consciousness in artificial intelligences and whether machines could become self-aware without us realising; and the neuroscientist Michael Graziano has argued that current theories of consciousness are “worse than wrong” while predicting that we’ll have built a conscious machine within 50 years.

Yet it’s hard to know what kind of mental life non-human animals actually have, and whether it is anything like ours. If it is, does that make it wrong to eat them? Or consider machines, which may develop mental lives of their own at some point. We’re ill-prepared to recognise if or when this will happen, even if we may eventually come to have moral duties towards machines.

The best thing I’ve read lately on consciousness in non-humans is the short story, The Hunter Captain, by the philosopher and fiction writer David John Baker. It involves an alien race that encounters a human being for the first time. According to their neuroscience, it turns out that the human lacks the special neural structure they believe necessary for generating consciousness. Like all the other animals they have encountered, including the talking animals they violently kill at the table before eating, the human is merely intelligent but lacks consciousness. As such the human has no moral status—she is something to be hunted, or enslaved. As you might expect, the human demurs. Some alien-human debate on the philosophy of mind ensues.

Baker’s story dramatises very well two key decision points we face when worrying about consciousness in non-humans. The first revolves around whether consciousness is the key thing needed for moral status—that is, the thing you have that generates moral reasons to treat you in certain ways (avoid harming you, respect your rights). Even if consciousness is key, it’s not clear where we draw the line: some say moral worth requires the kind of consciousness associated with feeling pain and pleasure (phenomenal consciousness), others point to the kind associated with self-awareness, or self-consciousness.

The second decision point surrounds the nature of consciousness, and whether a certain level or type of intelligence is enough. If so, just how clever do you have to be, and how do we measure that? Even if intelligence alone isn’t enough to warrant consciousness, it might not be psychologically possible for us humans to confront a highly intelligent being without feeling the urge that it is conscious. Should we trust that urge?

Consider, again, the octopus. We can tell from behavioral evidence that they are intelligent. But it is not clear how intelligent they are, or whether that is even the right question. Octopus intelligence is shaped, in part, by octopus needs—the kind of mind they have and need is dependent upon their evolutionary history, their environment, and their body-type. Given these factors, it makes sense to say that octopuses are highly intelligent. Consciousness might be closely tied to the particularities of human-like intelligence. But given how little we know about consciousness, it seems foolhardy to believe such a thing at present.

Other questions demand a hearing. Do octopuses feel pain? They certainly seem to, although the skeptic might claim that all they do is react to stimuli as if they were in pain. Are they self-aware? We do not know.

On these difficult questions, there is very little consensus. My aim here has been to work up to the questions. Because there is an obvious sense in which we all have to decide what to think about these questions. We all already interact with arguably conscious non-human animals of various levels of intelligence, and many of us will at some future point interact with arguably conscious machines of various levels of intelligence. Unlike Inky the wild octopus, speculation about consciousness in non-humans isn’t going anywhere.

In conjunction with Oxford University’s Practical Ethics blog.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.