Days before New York’s presidential primary, Hillary Clinton remains a strong favorite to win the Democratic Party’s nomination. She’s won more votes and more delegates than her only opponent, Senator Bernie Sanders, and stands poised to defeat him soundly in New York as well. At the same time, though, Sanders is gaining on Clinton in national polls, and has trounced Clinton in many recent small-state contests. He’s apparently decided not that he’s destined to lose, but that, to win, he must depart from the uplifting strategy he used to introduce himself to voters, and adopt an unsparing one, giving Clinton no quarter on just about any issue.

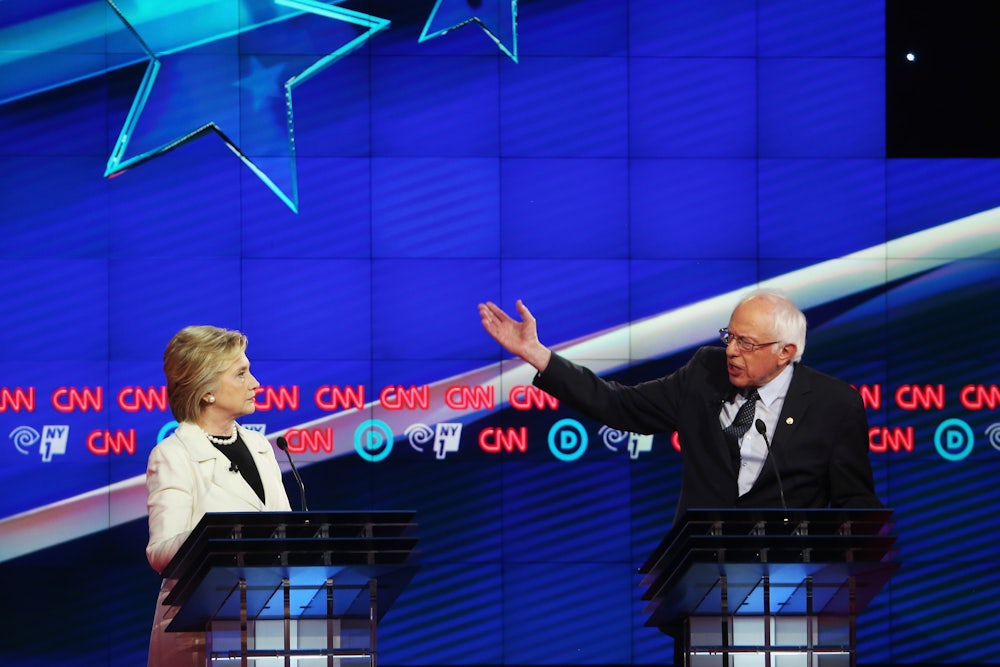

Over the course of two hours Thursday night, Sanders was merciless and at times contemptuous toward Clinton (who, as is her custom, gave as good as she got). Sanders practically mocked Clinton’s suggestion that the money she’s received (in pay and donations) from unsavory interests hasn’t corrupted her agenda. He criticized Clinton for deploying a “racist term”—“superpredator”—during the debate over her husband’s crime bill. Where they parted ways on issues, he attributed it to her establishmentarianism. Where they agreed, he mocked her as a Johnny Come Lately.

And yet, the ninth Democratic primary debate revealed almost no new daylight between Clinton and Sanders. It mainly just revealed that Sanders won’t go quietly into the night. Sanders was withering in his criticisms, but the criticisms were almost all familiar. Occam’s razor suggests his strategy is intended to avoid a blowout defeat in New York’s presidential primary on Tuesday, which would probably constitute a fatal blow to his candidacy.

And yet despite the campaign’s bitter turn, despite the fact that Sanders’s Hail Mary tack is much more likely to damage Clinton in the general election than to secure the nomination for himself, supporters should maintain a fondness for him as a fundamentally decent rival who has left Clinton, the Democratic Party, and the country better off. At the stage where all kindness has drained out of a campaign, most candidates find themselves tempted to sacrifice their remaining integrity to win. Sanders, by contrast, reminded skeptics why his supporters have been so loyal: With everything on the line, given the opportunity to obfuscate at Clinton’s expense, Sanders held firm even to views that promise to damage him in the state that could seal his fate.

Consider that in the same acrimonious debate, with the New York primary on the line, Sanders criticized Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Israel’s brutal military incursions into Palestinian territory, and called for Israel and the world to treat Palestinians with dignity and respect.

These views aren’t particularly controversial among Sanders’s core supporters. But they are—at least—risky views to espouse days before a Democratic primary in New York, where polls show Sanders behind by double digits.

They’re also not particularly popular views among mainstream Democratic politicians, including Clinton—or at least, most mainstream Democratic politicians don’t have the fortitude to express them publicly. But as with many, many issues this cycle, Sanders was willing to assume political risk, even when his only potential reward was to expand the sphere of legitimate debate within Democratic politics. Clinton and her supporters are clearly and understandably exasperated with Sanders’s debating tactics, but they ought to appreciate the fact that he rarely equivocates. This has been, for multiple reasons, to Clinton’s advantage as a debater and a campaigner.

Clinton is all too familiar with the nuisance posed by wily challengers who shape-shift and straddle issues. In the 2008 Democratic primary, Barack Obama enraged the Clinton campaign by attacking Clinton’s health care reform plan from the right, and pretending to oppose requiring people to purchase insurance simply because mandates and taxes are unpopular. That tactic may or may not have helped Obama win the primary and the general election, but it made the already complicated and painful task of reforming the health care system more complicated and painful when it came time for him to reverse his position.

In a similar way, Clinton—who has all along opposed setting the federal minimum wage at $15—attempted to co-opt the issue from Sanders Thursday night. Clinton supports a $12 wage floor, combined with local efforts in wealthier precincts to increase wages further. This has been her position all along, and yet on Thursday night she said she would sign $15 minimum wage legislation as president, as if Congress would send a Democratic president a larger minimum wage increase than she was seeking.

In some ways, on some issues, it’s easier for Sanders to avoid this kind of waffling, because his positions (single-payer health insurance, tuition-free college) are popular in the abstract among Democratic primary voters. But even where that’s not true, Sanders tends to be more transparent about his views than Clinton is about hers. Indeed, Clinton’s worst moments come when her mealymouthed instincts are juxtaposed against Sanders’s gutsier conviction politics. If Clinton learns the right lessons from that contrast, it will be to her advantage in the general election.

Late in the debate Thursday, Clinton sought to erase distinctions between herself and Sanders on issues like Social Security and climate change where Sanders is willing to call for higher taxes (on income above the payroll tax cap, and on carbon) and she is not. And yet, despite opposing the unpopular view that middle-income workers should pay higher income and consumption taxes, it was Clinton, not Sanders, who had to equivocate on the issue.

Sanders has simultaneously served as an unmoving target for Clinton, and shown, counterintuitively, that in politics an unmoving target can be as difficult to kill as a moving one. At times, his resolute progressivism allows Clinton to demonstrate her mastery of substantive policy (one of her most appealing qualities), but at others it serves to demonstrate where Clinton is hiding the ball, and to discourage her from doing so in the future. He is providing proof of concept that Democrats can stand forthrightly behind views they’re afraid to hold, and still exceed all political expectations. In a perverse way, it’s easier to become incensed at an opponent who makes self-righteous arguments than polite but disingenuous ones. Clinton certainly never wanted to draw a formidable challenger, but if she was destined to draw one, she’s lucky it was Sanders rather than anyone else.