When I got my purple GameBoy Color in 1998, the feature I was most

excited about was the little black infrared port on the top right corner. Certain

games, like Pokémon Gold/Silver, let you match the port on your GameBoy with

the one on a friend’s so you could trade items—supposedly, because it rarely

worked. To me, it seemed like an exercise in social futility. Here we were, my

friend and I, spending recess trying to line up our GameBoys exactly right instead

of just hanging out with each other. But those few times we got it to work, we felt,

for a moment, a complete, blissful nerdiness. (Which, in retrospect, probably

wasn’t worth the pain.) That was cool!

we’d shout together, watching new items appearing on our GameBoys.

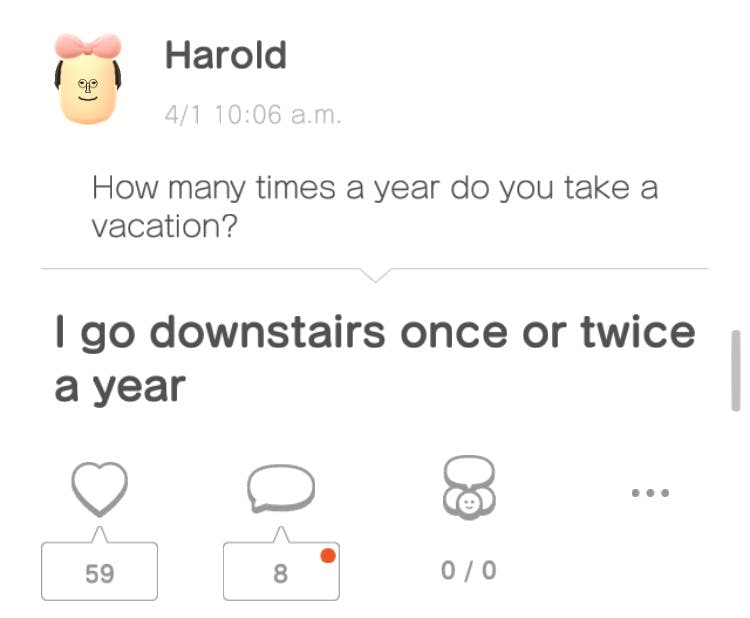

Nintendo’s newest venture, Miitomo—both a social network and the

company’s first app for iOS—feels much the same. Since its release, Miitomo has

reached more than 3

million users and quickly became the top free app in Apple’s app store. In

Miitomo, you make a Mii (pronounced “me”), Nintendo’s version of personalized

3-D avatar, which were pioneered in the Wii and 3DS consoles. Your Mii can look

as much or as

little like you as you want. After that you exist in a room, sometimes with

your friends, answering and asking computer-generated questions. Doing so helps

you to gain coins, tickets, and candy, which allow you to purchase things at

the Mii clothing shop and to play a fun pachinko-type game. There is no direct

chat function: Instead, as Nintendo describes

it,

you use your Mii as a “social go-between”—your Mii talks to your friend’s Mii

who talks to your friend. It’s a bit like passing notes through an infrared

port; it looks and feels like a combination of taking an online survey and

pressing through a video game’s NPC dialogue.

Which is all to say: If you’re trying to fulfill any normal social

function, in a way Nintendo did not explicitly build into the game, Miitomo is

frustratingly difficult to navigate. (Quartz calls it a “Kafkaesque

exercise in madness.”) Despite this, Miitomo has fostered innovative ways to

interact. To add friends, you either have to connect through Twitter, Facebook, face-to-face, or through mutual friends—which means that you presumably already know your Miitomo

friends in some way. These are the only

people you can interact with—as in real life, you can’t just walk into a stranger’s

house and talk to whomever’s inside. It defies the prevailing norm of most

social platforms, where interacting with (and tearing down) strangers is often

the name of the game. Take Twitter, which rewards conflict; Yik

Yak, whose anonymity promotes harassment; and Reddit,

whose forums are rife with hate speech. Maybe it’s because Miitomo is

structurally a more intimate friendship network—or maybe because you’re

projected through a caricatured representation of yourself—but the app seems to

promote constructive interactions instead of negative ones. Users poke fun at

the computer’s questions rather than each other and there’s no fear that your

answers will be retweeted to 100,000 followers with the comment, “this is dumb

af.” Honestly, no one really cares what you have to say at all, aside from the

people you’re already friends with. And your Miitomo friends are probably your nerdier

ones; in my case, they played Pokémon growing up and have screenshots of their

best Neko Atsume cats saved to their camera rolls. I have a theory that this

encourages Miitomo users to be as stupid and obscurely referential as they

want.

Some questions the app might ask: What did you do last weekend? What would be the worst job in the world if you had to wear roller skates all day? Do you believe in aliens?

Unlike Nintendo’s other social offerings, there seem to be very few constraints

on what you are allowed to say on Miitomo. (The only time I got a warning

message for unsavory language was when I tried to make the app pronounce my

name as “Oh shit truuu.”) It feels less like

a space for kids and more like a territory for Twitter jokes and former

Something Awful users. The best jokes—which distinguish the best jokers—come

from Miitomo’s Miifoto function. Undoubtedly the highlight of the app, Miifoto

allows you to throw your Mii onto any picture on your phone. It’s the newest

frontier for the dumb-genius netizens.

— Shigeru Miyamoto (@RealShigeruM) April 4, 2016

Miitomo’s sudden popularity probably has much to do with this function: There is surprisingly little already out there that lets you do what you can with Miifoto. It’s basically an infinitely customizable emoji that carries your own distinct imprint—your Mii. I’ve spent hours making them and snickering to myself before sharing them with my friends, who will definitely, probably, get the joke. I don’t use the app for communication, but creative collusion. It’s an escape from the all-too-public and judgmental universe of Twitter and from Facebook’s drudgery.

But even within the first month, I find myself opening up Miitomo less and less. The jokes have gotten old, and I have run out of funny photos of the fat cat that I live with to post on Miifoto. I suspect this is true of many of Miitomo users: Unless Nintendo comes up with more features and functionality (although it seems they will soon turn their attention towards the release of new apps), it’s unlikely that Miitomo’s popularity will persist. At the time of this writing, a month or so after its release, the app has already slipped to 67th on Apple’s free app chart. It’s right behind Tinder, another social-connection app that seems past its prime.

now what do i do. this app sucks pic.twitter.com/W8oeXKgp5u

— leon (@leyawn) April 6, 2016

Anyway, as many have pointed out, Miitomo was probably created just so

that Nintendo can mine

our data. If that’s true, the app’s limited functionality may just be Nintendo’s

way-too-real parody of a social network. It’s like they’re saying, “Ha ha!

Socialization online is futile and dumb. But we will take your data anyways.”

Or maybe they really are just that bad at social apps. Either way, my guess is

that the Miitomo fad will fade quickly. Today, my GameBoy sits in a drawer

somewhere, quietly leaking acid from its defunct batteries. Most likely, my

Miitomo app will soon face the twenty-first century equivalent. It will eventually move

into my iPhone’s graveyard—the folder that houses Compass and Stocks.